Sonja Sekula: Where Art History Meets Mental Health

Open about being a lesbian, regularly hospitalized for mental health challenges, working on a small scale when other Abstract Expressionists worked large ... Sekula's differences limited her fame.

I hadn’t ever heard of Sonja Sekula before, which is one of the amazing things about the Internet and its rabbit holes. I subscribe to

and their links led me to an Artnet article titled Four Overlooked Women Abstract Expressionists Are Spotlighted in London, which introduced me to the Abstract Expressionist and her interesting story of creativity, mental health, and how both intersect with society. What caught my interest immediately was this sentence:“It has been recorded that during frequent hospitalizations in psychiatric wards, doctors tried to cure Sekula of her homosexuality.”

I had to know more so I began to read. Sekula was born in Lucerne, Switzerland in 1918, but her family moved around a lot, and she eventually landed in New York City at the age of about 18, where she quickly immersed herself in the art scene. She studied under George Grosz and Morris Kantor, connected with André Breton, was roommates for a time with dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage. She would go on to develop many artistic friendships, such as with Frida Kahlo, and collaborations, like with Max Ernst. Early on, she began exhibiting her work with Peggy Guggenheim and then shortly later with Betty Parsons.

But that latter points to one of the challenges she was to face as a female artist in New York at the time, although she had five solo exhibitions there over the span of about a decade. The leading male artists of the era, including Pollock and Rothko, had opinions about the gallery’s expansion, with an emphasis on distaste for the female artists increasingly included in the gallery. The New York Times referred to some of Sekula’s works there as “trifles.” Parsons, for her part, continued to support Sekula and her work. Still, immediately after her third show opened there, she had a nervous breakdown, which I’ll get to in a moment.

Her mental health was an issue from the time she was in her early twenties, both in terms of its impact on her creative process and in how her work was viewed by the larger art world. Sekula started experiencing depression, anxiety and mood swings probably in her teens. According to one timeline of her life, she attempted suicide at age 20. In her early twenties she was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a diagnosis which still carries stigma today but was even more stigmatized at that time. She was frequently hospitalized, sometimes for long periods of time. We don’t have an exact account of what treatments she received in the hospital, but given the locations and the timing of her stays, there’s likelihood of a combination of insulin shock, metrazol-induced seizures, and ECT.

At times, the institutional stays interrupted her creative work. At other times, she was allowed to create in those institutions and this gave her focused periods of intensity. Throughout my research, I’ve found that asylums/institutions seem to go through cycles of whether or not they approve art/craft as therapy and provide freedom for various forms of self-expression or they are more restrictive, limiting, and don’t allow for creativity. It seems that she experienced both situations. Her creative productivity tended to go through cycles, and it’s hard to tell if that was a result of the moods and inspiration of her mental health, the status of her hospitalization, or (likely) some combination of both.

I find myself wondering how her creative work might have sometimes led to symptoms. In 1951, as I mentioned, she experienced a nervous breakdown the day after a show of hers opening at Betty Parsons, something that doesn’t seem like a coincidence. Was she staving off symptoms the whole time, channeling them into her work, and then the show was the release that let her break down fully? Was there something about the work being finished that triggered an emotional reaction? Was it the opening of the show to the public and concern about the reception (which turned out to be overwhelmingly positive but she didn’t know that at the time)? Maybe it was all or none of these things. We can’t know. But I suspect there’s some correlation there.

In a 2021 American Art journal article, Jenny Anger shares insights about the hospitalization from the artist’s letters. She doesn’t appear to have access to full art supplies but references making “bright potholders to calm to the imagination” as part of her occupational therapy. In a letter to John Cage, she laments that her life in the institution is music-less. She was there for over a year and did the long slow work of healing. Anger writes:

“Released from the hospital near the end of 1951, she set to work right away on what would be her largest work, The Town of the Poor (frontispiece). Hospitalization--not psychotic visions--clearly helped return her to her full creative powers. This painting would be the centerpiece of Sekula's fourth solo show at Parsons's gallery in March 1952.”

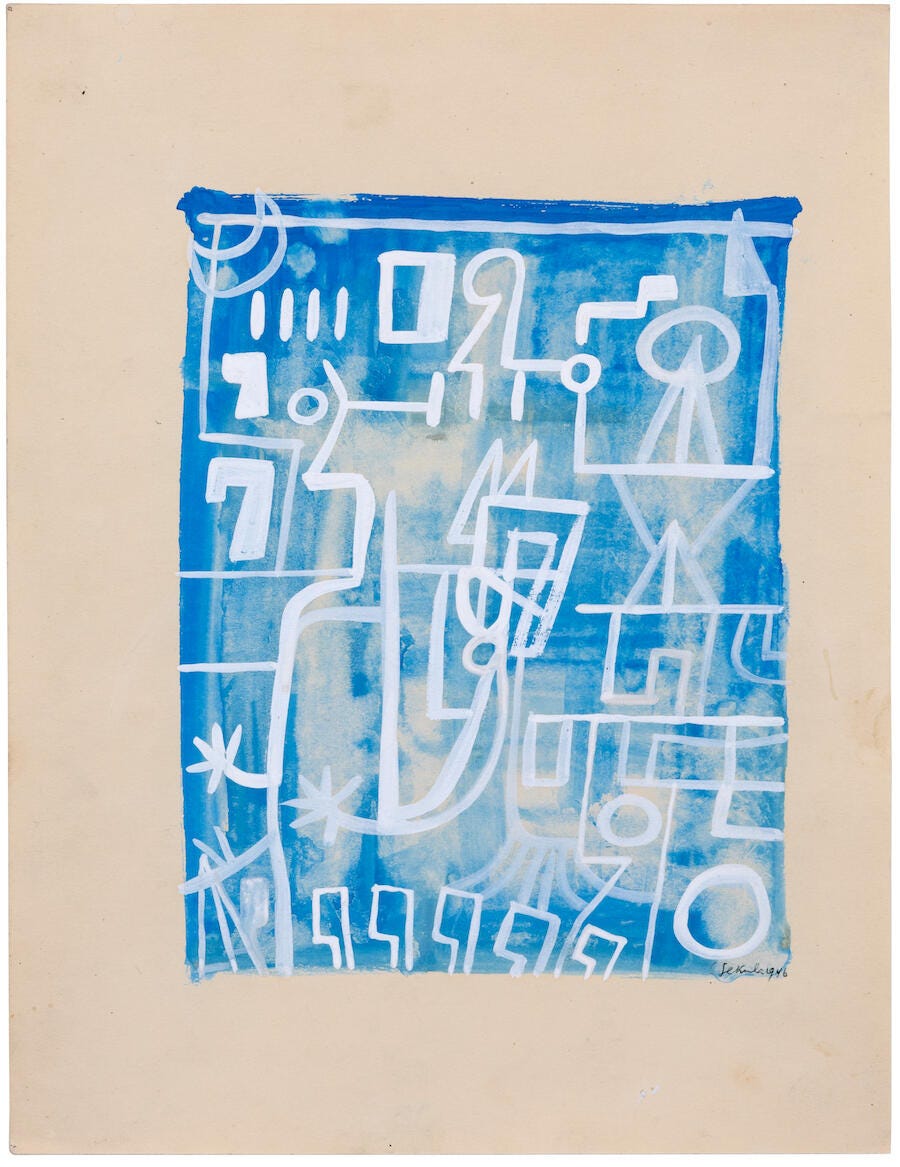

Sekula generally expressed that art was helpful for her, a form of self-therapy that allowed her to express emotions that she didn’t always know how to express otherwise. But, of course, it was complicated. Her identity as an artist was deeply intertwined with her experiences with schizophrenia. Her perception by others was often impacted by awareness of her diagnosis. Her works were often seen as extensions of her mental state, with all the implications that may have had for different people. She had early success with her work; her first solo show was with Peggy Guggenheim in 1946. However, her recurrent hospitalizations and the limited understanding of schizophrenia at the time affected her ability to sustain a continuous presence in the art world.

And, returning to the quote that first caught my attention, her perception by others in the art world was also complicated by being very open about her homosexuality. After all, it wasn’t until 1973 that homosexuality was removed from the DSM so people still stigmatized that as a mental health condition as well. Sometimes the art scene was more accepting of the wide breadth of human sexuality, sometimes not, and often this was used against her. And often, she was “treated” for it … Richard G. Mann writing for GLBTQ says:

“During her stays in clinics, Sekula was subjected to a harsh regimen of treatments, including frequent shock therapy , injections with various mind-altering drugs, and wet-sheet wraps. From the 1930s through the 1950s, many leading psychologists considered lesbianism a symptom of profound mental disorder . In this context, it is perhaps not surprising that her doctors repeatedly sought to "cure" her sexual orientation, which they regarded as a debilitating manifestation of schizophrenia.”

To that, a terrific and beautifully written response comes from her 1960 journal, at least according to Wikipedia:

1960: "Let homosexuality be forgiven, let us hope that she will be welcome in the Greek mythology and protected by pagan nature gods as well for most often she did not sin against nature but tried to be true to the law of her own - To feel guilt about having loved a being of your own kind body and soul is hopeless - let us hope there were many pure moments in each of these attractions and loves - into which the realm of sphere and eternity and silence entered as well.”

Sekula was underrecognized throughout her lifetime. MoMA summarizes this well:

“Yet her refusal to adhere to a singular style (“It’s too bad she didn’t pin herself down, but that’s the way she was,” said the artist Morris Kantor)2; her transatlantic position (“Am I a Swiss, or an American painter?” she wrote in her journal in 1961)3; her identity as a gay woman (she lacked the prominent male artist or critic partner that aided the visibility of other female artists of her generation); and her struggle with mental illness (which led to her untimely death from suicide at the age of 45) all contributed to Sekula’s underrecognition.”

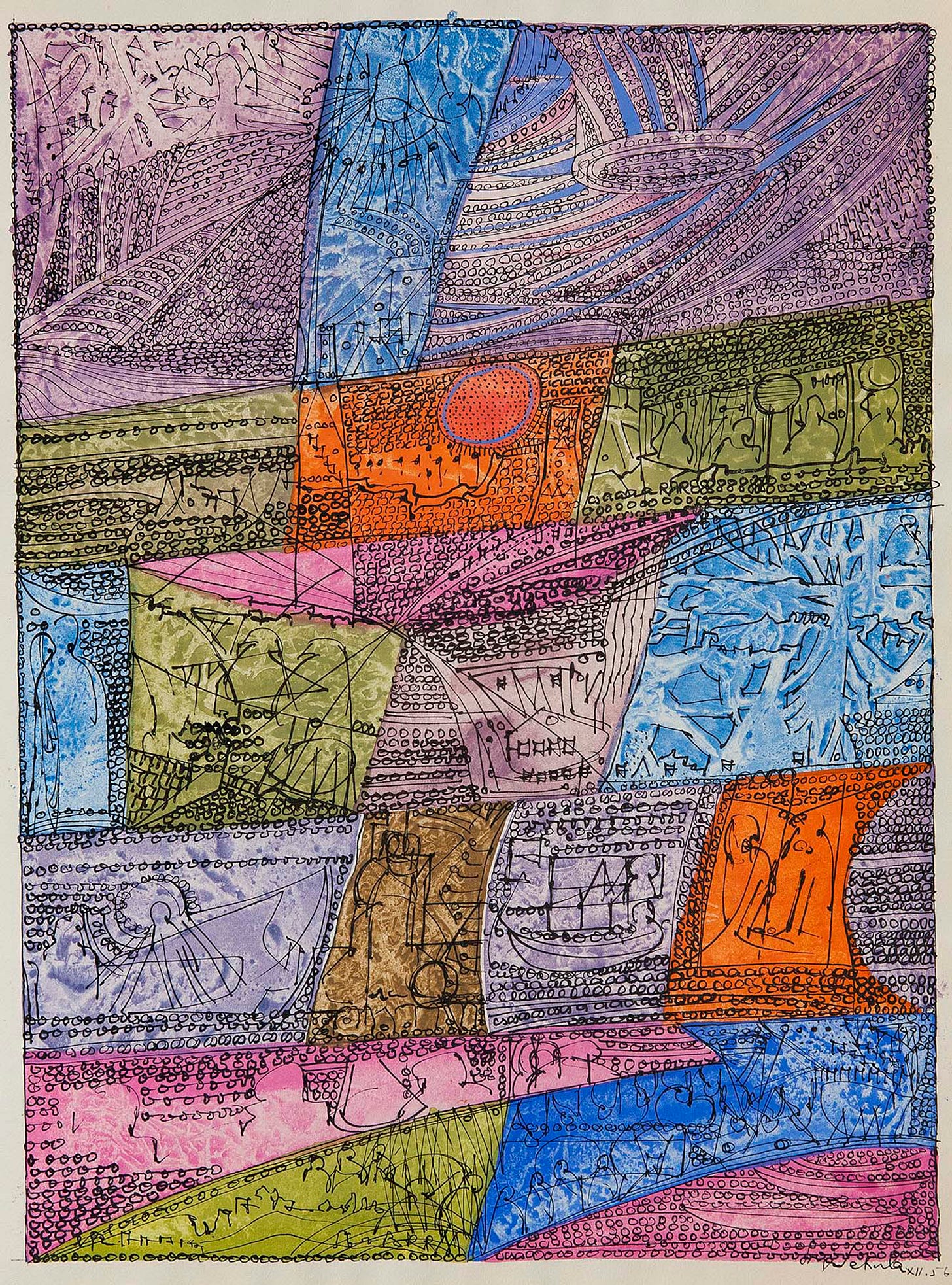

Regarding her “refusal to adhere to a singular style,” I love this from the artist herself, written in 1957, published in a 1971 Art in America article titled Who Was Sonja Sekula?, the title itself speaking to how she had disappeared from public awareness at the time:

“The reproach I often received at not following one definite line I cannot understand. For I am many and I reflect the left and the right and attempt to stand up and lie down wall-lessly in the shadow and in the light of my hands, soul and heart.”

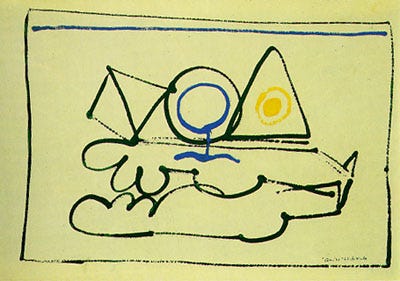

MoMA also says speaks to the scale of her work; in her lifetime, her large paintings were well-received, but she’s better known for working small. MoMA says that she would travel to Switzerland regularly because mental health care was more affordable there, and one of the reasons that she would draw on paper and otherwise work “small” was because doing so offered portability. For example, in the aforementioned timeline, we see that in 1952 she went to Switzerland with her mother to go into a sanatorium where she stayed for about a year.

Working small was practical for cost, availability of materials, and portability, but that wasn’t the only reason the artist did so. Anger quotes a letter from the artist about choosing to work small even though her American buyers prefer her large works:

"I work often on paper with oil, small size, as that suits my heart best--Yes, I have big canvases, new, but the point does not go after size and American public must have bigness. O.K. But I stick to my own need and prefer to work small scale for outward and moral reasons."

Grace Glueck for the New York Times wrote:

“As her world diminished, Sekula's work became more modest in scope, less publicly oriented and more inward-looking. Of no small interest here are the collages, sketchbooks, haiku and poem-drawings of her last years, as she shook off the art world and entered into a vivid dialogue with herself.”

But then Anger also quotes:

"Would like to paint on a big canvas, in my mind I try and try to do it--but am subconsciously discouraged at having to hide it all again in some dusty storage place."

This shows the multiple factors that are at play: her own desires and preferences as an artist vs. her potential concerns about what buyers want, the realities of her situation and the way they impacted the scale of her work, the mental health impact of having to store large pieces causing her to want to perhaps not create them at all … it’s a complex web, as the true nuanced relationship between art and mental health often is.

Jenny Anger posits, quoting Griselda Pollock, that her return to Switzerland was a large contributing factor to the decline of her art career.

“Extended hospital stays with various treatments appear to have helped her, and support networks large and small--and their failings--impacted her life and production profoundly. Some fellow artists appear to have seen Sekula's illness poetically, sometimes with dire consequences. She had other artist friends and acquaintances who helped her in times of need, and gallerist Parsons supported her through thick and thin. With all of these factors in mind, it is my contention that Sekula's return to Switzerland for affordable treatment ruined her career; as the move's result, her personal and professional base fractured and her exhibiting career in the United States came to an abrupt end. As art historian Griselda Pollock has speculated, "Exile by coming 'home' broke the thread of what might have become a more recognized and sustained American career, even if punctuated by recurrent illness." Sekula's case reminds us of how critical a supportive environment and a community of like-minded people are for the production and reception of art.”

She elaborates with this quote from the artist in Switzerland circa 1953: "I am unable to meet people or galleries, etc. or do much about it as my nerves seem just strong enough to even go on painting + not much more anymore."

Sekula persisted with her art as much as possible, but in the 1950’s and 60’s, her mental health declined and she was hospitalized more frequently. According to the timeline, she went into a New York hospital in 1954 for another year. According to Angerm, she had desperately wanted another show at Parsons, and she returned to New York for that, but the show had to be canceled due to her mental health and subsequent hospitalization. In 1956, she spent a couple of months hospitalized in Switzerland. She’s hospitalized again from autumn 1958 to spring 1959, the last half of 1960, the month of May in 1961 and then again in early 1963.

There’s a devastating excerpt from one of her letters in Anger’s article in which she expresses how lonely she feels in Switzerland and how she’d be much happier in New York but the cost of medical care in America was too prohibitive she felt stuck getting care in Switzerland. And her letters/journals from this time excerpted in the 1971 Art in America piece, speak volumes about her mental state in her last years, her perception of the world, her place in it, her art …

1962: “No more color upheaval and joy and greed for what a color might become. My gray drag possibility now is year old, a many year old wail and complaint for the birth of a child. I want my child to be the birth of a painting. I need a father for my child. … I am blind in the eyes and blind in the spirit and bound to the cellar prison of my existence and outward room.”

1962: “I cannot say how often it hurts to tear up work, to destroy such bad work. I feel it was not pure enough, not gifted enough, all-ways impatient, rarely the way my inward eye wants it. My hands is poor to do what the spirit in me asks for. All this work is conditioned by intense mortality and often Fear.”

Sonja Sekula died by suicide at age 45 in 1963. Off and on, she was creating the entire time. She had a solo exhibit in Zurich. She created her Meditation Boxes, among her last works. And it was in her studio that she died.

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

Thanks for reminding me about Sekula! Her work is incredible, right there in the middle of big artistic movements, and bold and unafraid. I got into abex for a while there.

Artists by definition engage in a type of emotional instability. A "normal" person doesn't interrogate themselves the way artists do. As someone once said about the avant-garde novelist William S. Burroughs, he routinely goes places no one in their right mind would go.