The Role That Alfred Stieglitz Played in Georgia O'Keeffe's Creativity and Mental Health

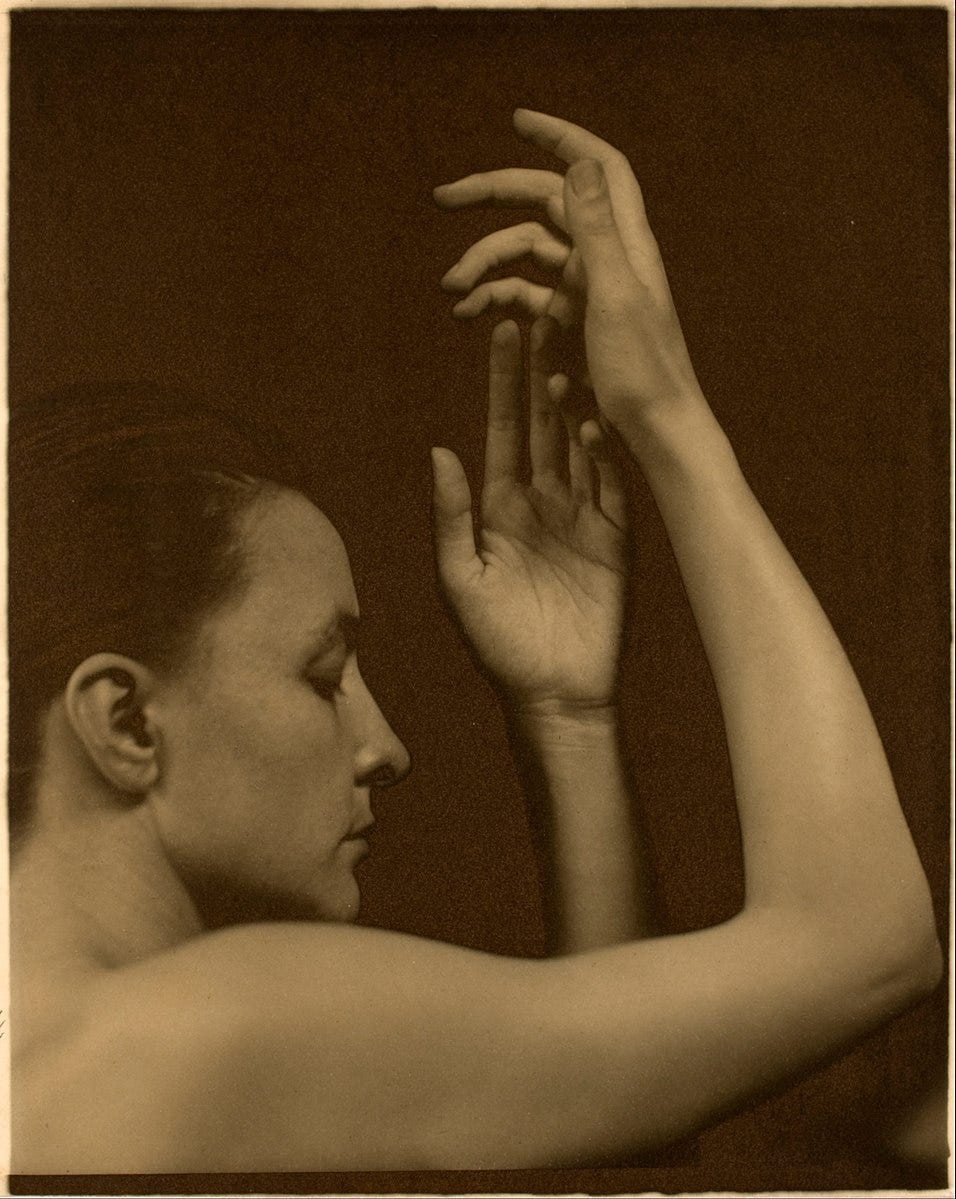

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz had a complicated relationship with one another as she effectively replaced not only his wife Emmy. O’Keeffe is quoted as saying, “he photographed me until I was crazy.”

The story of O’Keeffe’s relationship with Alfred Stieglitz and its relationship to her creativity and mental health made up only a few lines in the published version of The Artist’s Mind: The Creative Minds and Mental Health of Famous Artists. But it made up so much of her life … here is a longer version.

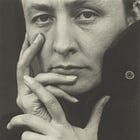

Georgia O’Keeffe was engaged in a turbulent decades-long relationship with high-profile artist-photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who in many ways inspired her art career, but who also contributed significantly to her emotional ups and downs.

When Stieglitz’s daughter Katherine, or Kitty as she was called, was born in the late nineteenth century, the photographer made it his goal to document her entire life in photos. His then-wife Emmy thought he was ruining their daughter’s life by following her around with a camera and put an end to it.

(How normalized this has become in the age of digital cameras and social media …)

Stieglitz never forgot this dream, though, and when he met O’Keeffe, she replaced Kitty as his muse for this lifelong documentary project. O’Keeffe is quoted as saying,

“he photographed me until I was crazy.”

Stieglitz documented every part of O’Keeffe’s changing body over the course of about two decades, beginning when she was 30 and he was 53. At the start of their affair, in 1918, Emmy caught the two of them in a risque photo session. She threw Stieglitz out, and he moved in with O’Keeffe, at which time his daughter Kitty cut off all contact with him.

After a few years, O’Keeffe wanted to have a child of her own. But Stieglitz, nearing 60, had no such interest. This was complicated by the fact that in 1923, Kitty had a child, after which she experienced severe postpartum depression.

Steiglitz “could not imagine Kitty working herself out of her depression, he could only imagine sterilizing her.”

This postpartum depression was one of many reasons he gave to O’Keeffe about why they could not have a child together; he argued that he was cursed. The family blamed Stieglitz for Kitty’s breakdown; instead of attributing it to postpartum depression, they believed it was due to his affair with O’Keeffe and the divorce from Emmy. The divorce came through in 1924 and he immediately insisted upon marrying O’Keeffe, with whom he had already been living for six years.

Kitty’s doctors suggested that perhaps if Stieglitz and O’Keeffe did indeed marry then Kitty would be able to process their relationship and move on.

“O’Keeffe was expected to provide sympathy for the disasters his own family had become and the guilt he bore for it.”

Thus, she begrudgingly acquiesced to the marriage, which, of course, didn’t help Kitty at all. Kitty was eventually re-diagnosed with dementia praecox (an outdated diagnosis most closely matching modern-day schizophrenia) and spent the rest of her life institutionalized.

And so, O’Keeffe and Stieglitz had a complicated relationship with one another as she effectively replaced not only his wife Emmy, but also his daughter Kitty, due to their difference in age, his paternalistic attitude, and these complex family dynamics. This impacted and intersected with O’Keeffe’s self-perceptions and self-esteem, perhaps causing anxiety and emotional swings in response to the demands the relationship placed upon her. Often, she would leave New York City with an excuse for painting but mostly she just needed a break from Stieglitz.

Years later, Stieglitz would repeat history when he left O’Keeffe for a much younger woman, Dorothy Norman, who became his new photographic muse. By the early 1930s, he was obsessively photographing Norman. The two were practically obsessive with one another, seeing each other daily, repeating “I love you” or simply “ILY” over and over again.

Obviously, this wasn’t easy for O’Keeffe,. She went to stay with her sister where she suffered a racing heart, ongoing headaches, and crying jags, all symptoms of both anxiety and depression. She likely experienced the heartbreak and grief of the loss but also the re-imagining of who she herself was if she was no longer the young muse but now the tossed-aside woman. Stieglitz showed up at her sister’s apartment and O’Keeffe’s condition worsened. This, too, paralleled Kitty’s response to the man; according to biographer Nancy Scott, “his presence set off her fits of rage.”

By early 1933, O’Keeffe had checked herself into a hospital for treatment. She was diagnosed with “psychoneurosis,” which was their way of saying that her emotions were pent up without the expressive outlet they needed, and had manifested into physical symptoms. O’Keeffe stopped painting for about a year as she struggled through this time.

This is what depression can do: it can take away the artist’s ability to create. There is a fine balance for the artist - art can be such a source of catharsis, self-esteem, and strength to get through depression but depression can overtake the artist and immobilize them to the point where they can’t work on their craft.

Depression is characterized by a loss of interest in things that once gave you pleasure, as well as feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness, all of which can coalesce into a major creative block.

If we use my lens of the two intersecting spectrums: where one exists in terms of mental health on one axis and on the other in creative impulse, it seems that at this time her mental health was such that it hindered her creative drive. This wouldn’t last forever but is an example of how when things get so challenging in our mental, emotional, relational words, it can cause the art to stop.

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

You Might Also Want to Check Out:

Sources/ Works Cited:

Boxer, Sarah. “Georgia O'Keeffe, That Crazy Little Girl,” The New York Times, August 1, 1997

Bullen, Daniel. “The Love Lives of the Artists: Five Stories of Creative Intimacy.” Counterpoint Press. 2013.

Laing, Olivia. “The Wild Beauty of Georgia O'Keeffe,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, July 1, 2016),

Prypchan, Lida. Medium. “Georgia O’Keeffe: Part 1.”

Rose, Phyllis. “Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters.: Yale University Press. 2019.

Scott, Nancy J., Georgia O'Keeffe (London: Reaktion Books, 2015).

This is so interesting, yet also painful to read. Stieglitz comes across as quite a force of destruction (except in terms of his own work, of course).

So interesting. During my graduate studies, I took several art and art history classes in which O'Keefe was the subject (and, by association, Stieglitz). Since my focus (Humanities: Literature and History) was on the modern period in America, I ran across several women writers and artists whose health suffered as a result of relationships with men who either used them as a muse (I laugh at that term now) or, as in Alfred's case, objectified them. I'm thankful to see another woman artist telling the story of a sister-artist who suffered in this way.