The Impact of Hysteria Diagnosis on Women in Art History

How Camille Claudel, Dora Maar, Emily Dickinson and others were affected by an outdated psychological diagnosis that pathologizes women's creativity

The terms histrionic and hysteria as a diagnosis are problematic for many reasons relating to art history’s intersection with mental health. More than anything, the problem is that these terms were applied mostly by men mostly to women, disregarding the benefits of feminine emotional lives and belittling some of the struggles. As I began a comprehensive look at various psychological terms that were once used and are now considered outdated, then, I'll start with HYSTERIA.

Hysteria in Mental Health History

The term "hysteria" has a long and complex history in mental health diagnosis. The ancient Greeks believed that hysteria was caused by a "wandering uterus" that could move around the body and cause various symptoms. In the Middle Ages, hysteria was often seen as a form of possession by demons or other supernatural entities.

In the 19th century, hysteria became a popular diagnosis among European and American doctors, who believed that it was a condition caused by a malfunctioning of the female reproductive system. Symptoms of hysteria included nervousness, anxiety, depression, and physical symptoms such as muscle spasms, paralysis, and convulsions.

However, as medical knowledge advanced, it became clear that hysteria was not a physical condition caused by the uterus or any other specific organ. Instead, it was recognized as a psychological disorder characterized by a range of physical and emotional symptoms.

Sigmund Freud, naturally, was one of the most influential figures in the history of hysteria diagnosis. He believed that it was caused by repressed emotions and unresolved psychological conflicts, and he developed his style of psychoanalysis to largely to “help” his patients who he frequently diagnosed with the condition.

In the early 20th century, the term "hysteria" fell out of favor among mental health professionals, who recognized that it was stigmatizing and had been used to pathologize women's emotions. Today, the symptoms that were once called "hysteria" are recognized as part of a range of mental health conditions, including anxiety disorders and somatic symptom disorders.

“For example, the famous case of Bertha Pappenheim – popularly known as Anna O. – illustrates neurologists’ frequent carelessness when dealing with relevant information about female patients’ life experience, details which might speak about the presence of certain symptoms differently. Before her hysteria diagnosis, Pappenheim had tragically lost her father to a terrible illness, an event that triggered an onset of psychosomatic symptoms which, per modern research in psychiatry, would rather point to a post-traumatic stress disorder.” - The Theater of Hysteria: Pathologization of Female Excess in 19th Century Photography - Michaёlle Lahaye, Yiara Magazine

So, yes, there were symptoms that women experienced, some of which were individually distressing, most of which conflicted with how to live in the norms of society, and those symptoms are still very real experiences today for many people but “hysteria” isn’t the right term for them. (And, of course, diagnosis is a tricky thing that’s right for some people and not right for others.)

Impact of Hysteria Diagnosis on Women Artists

Hysteria was often a catch-all diagnosis for a wide range of behaviors that deviated from the societal norms expected of women, including expressions of independence, sexual desire, or dissatisfaction with domestic roles. The medicalization of these behaviors served to pathologize normal female experiences, framing them as illnesses rather than valid reactions to oppressive circumstances. This diagnosis became a tool of control, used to justify the exclusion of women from education, professional careers, and public life, reinforcing their subordinate status in society.

For women artists, the impact of a hysteria diagnosis was particularly devastating. The very qualities that are often essential to artistic expression—emotional depth, creativity, sensitivity, and a keen awareness of one's surroundings—were pathologized as symptoms of hysteria. Women who exhibited these traits were labeled as unstable and mentally ill, rather than being recognized for their artistic talents. This stigmatization not only devalued their creative work but also marginalized them within the art community.

The diagnosis of hysteria also had practical implications for women artists, restricting their access to artistic education and professional opportunities. Institutions that offered training in the arts were often closed to women diagnosed with hysteria, as they were seen as incapable of handling the rigors of artistic study or the demands of a professional career. Even if they managed to pursue their art, these women faced significant obstacles in gaining recognition and respect for their work. Their artistic contributions were frequently dismissed or diminished, their work interpreted through the lens of their supposed mental illness rather than as expressions of their creative genius.

Plus, the label of hysteria often led to women artists being subjected to abusive treatments that further hindered their ability to create. Many were confined to asylums or subjected to treatments such as forced rest cures, electrotherapy, or even surgical procedures, all of which could have lasting physical and psychological effects. These treatments not only stripped women of their autonomy but also deprived them of the time, space, and mental clarity needed to pursue their artistic endeavors.

The broader cultural impact of the hysteria diagnosis on women artists also cannot be overlooked. By pathologizing traits associated with artistic expression, the diagnosis reinforced the notion that women were unsuited for the arts, thereby justifying their exclusion from the cultural and intellectual life of their time. This exclusion had long-lasting effects, contributing to the erasure of women artists from the historical record and limiting the diversity of voices and perspectives in the art world.

Artists Diagnosed With Hysteria

Some examples of the artists diagnosed with hysteria or very similar terms include:

Camille Claudel

Camille Claudel was a French sculptor who was active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She is best known for her powerful and emotive sculptures, which often depicted figures in states of emotional or psychological intensity.

Claudel's sculptures were marked by their expressive power and intense emotional content, which was influenced by her own personal experiences and psychological struggles. She was known for her unconventional lifestyle and personal beliefs, and was often subject to criticism and scrutiny from her peers and critics.

Claudel's own writings and correspondence suggest that she struggled with a number of personal and professional challenges throughout her life, including financial difficulties, health issues, and the loss of several close family members and friends. She was also diagnosed with hysteria by her doctor, who believed that her emotional and psychological struggles were linked to her menstrual cycle.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Author of the semi-autobiographical novel The Yellow Wallpaper, the writer was diagnosed with hysteria. The story has been associated with postpartum depression as well as the historic diagnosis of neurasthenia, which I’ll be writing about more soon. In any case, the writer herself was diagnosed with hysteria and given "the rest cure" upon which the novel is based.

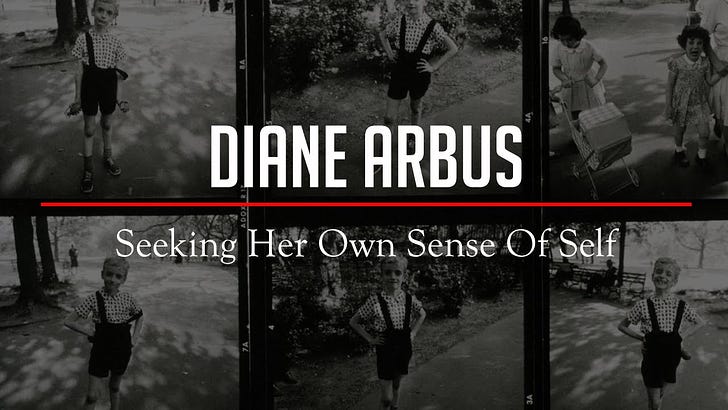

Dora Maar

Dora Maar (1907-1997) was a French photographer, painter, and poet. She is best known for her work as a surrealist photographer and for her relationship with the famous Spanish artist, Pablo Picasso.

Maar met Picasso in 1936, and they began a tumultuous love affair that lasted for nearly a decade. During this time, Maar became an important muse and collaborator for Picasso, inspiring many of his works and appearing in some of his famous paintings, such as "Weeping Woman." In various biographies and accounts of her life, Maar is often described as having experienced periods of deep melancholy, anxiety, and emotional instability. Some scholars have suggested that these struggles may have been exacerbated by her tumultuous relationship with Picasso and the emotional toll it took on her. She has variously been said to have experienced depression or hysteria.

Some of Maar's surrealist photographs and paintings do explore themes of psychological and emotional distress, anxiety, and trauma, which could be seen as related to or evocative of the concept of hysteria in a broader sense. For example, her 1935 photograph "Portrait with Hand," which depicts a woman's disembodied hand gripping her own face, has been interpreted as a commentary on the experience of psychological fragmentation and dissociation.

Similarly, her later paintings, which often incorporate surreal and abstract elements, can be seen as a reflection of her own psychological struggles and emotional turmoil. Many of these works feature distorted or fragmented forms, vivid colors, and ambiguous or unsettling imagery that suggest a sense of psychological unease or disturbance.

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson's life and work have been the subject of much scrutiny and speculation, and there is ongoing debate among scholars about the nature and extent of any psychological or emotional issues she may have experienced.

During her lifetime, the term "hysteria" was often used to describe a wide range of physical and emotional symptoms that were believed to stem from an underlying disturbance of the female reproductive system. Dickinson's letters and poetry suggest that she did struggle with a number of physical and emotional issues throughout her life that could be interpreted as related to or reflective of the broader cultural and medical discourse around hysteria.

For example, Dickinson suffered from frequent bouts of illness and physical discomfort, including headaches, neuralgia, and digestive problems. She also experienced episodes of extreme emotional intensity and agitation, as well as periods of withdrawal and isolation. These symptoms have been attributed by some scholars to various psychological or physiological conditions, such as anxiety, depression, or a possible neurological disorder.

In her poetry, Dickinson often explores themes of inner turmoil, psychological distress, and existential questioning, as well as the limits and possibilities of language and communication. Some of her most famous poems, such as "I felt a Funeral, in my Brain," "After great pain, a formal feeling comes," and "The Soul selects her own Society," can be seen as reflections of her own psychological and emotional struggles, and have been interpreted as evocative of the broader cultural preoccupation with hysteria and related issues during her lifetime.

Florence Nightingale

English nurse and social reformer Florence Nightingale, who is widely regarded as the founder of modern nursing, was born in 1820 into a wealthy and privileged family, and was initially discouraged from pursuing a career in nursing due to its low social status at the time. Nevertheless, Nightingale was deeply committed to the idea of nursing as a profession, and spent several years training and working as a nurse in hospitals and clinics throughout Europe. During the Crimean War, she gained international recognition for her work as a nurse and for her efforts to improve the conditions of military hospitals and medical care. Nightingale was also a vocal advocate for public health and sanitation, and believed that poor living conditions and inadequate medical care were major contributors to the high mortality rates and poor health outcomes of her time. She conducted extensive research and wrote extensively on public health issues, and her work laid the foundation for modern healthcare practices and policy. And yes, it has been reported that she experienced hysteria.

Surrealists

A number of the surrealists were influenced by the hysteria diagnosis. And sometimes glamorized it:

"Hysteria is by no means a pathological symptom and can in every way be considered a supreme form of expression." - source

The Surrealist movement emerged in the early 20th century as a reaction against the rationalism and materialism of modern society. Surrealists believed that the unconscious mind held the key to artistic and intellectual freedom, and sought to explore the irrational and fantastical elements of human experience.

In the context of the Surrealist movement, hysteria was often seen as a form of rebellion against the strict social norms and conventions of the time. Surrealists viewed hysteria as a kind of "psychic revolt" against the repressive and limiting aspects of modern society, and saw it as a potential source of artistic inspiration.

Surrealist artists often depicted dreamlike and irrational scenes that were infused with psychological and emotional symbolism, and saw the exploration of the unconscious mind as a way of tapping into a deeper, more authentic form of creativity. The Surrealists also saw the exploration of psychological and emotional experiences, including those associated with hysteria, as a way of challenging traditional gender roles and hierarchies, and of opening up new possibilities for personal and social transformation.

Recommended Viewing: "Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch's Accuser”

“The creative journey to realize Vireo began over 20 years ago at Yale, where Bielawa was a literature major working on her senior thesis. During the course of her research, she repeatedly encountered groups of men -- neurologists, priests, the Surrealists -- who were obsessed with authoring studies on teenage girls' visions and what those visions meant. Parisian doctors in the 1890s were fascinated with hysteria, and 50 years later, the Surrealists wrote a collaborative essay celebrating hysteria's anniversary.

"What you're missing in many of these texts, of course, is the voices of the young girls. There's this silent author in there, and I was captivated, bewitched by that," she says. "A yearning to know more about these girls who were silent yet so documented. I came away thinking, 'Gee, a scholarly essay is not the best place to explore this.' - PBS

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

A Feminist Art Exhibit Begins with Hysteria

A few years ago, I reviewed a feminist art exhibit that began with a room that introduced the concept of hysteria:

DiQuinzio explained that this room was her way of “setting the territory”. womxn have had to overcome so much in society and history. The diagnosis of hysteria is one prime example. Basically, white cisgender male doctors pathologized womxn’s every emotion. They sometimes forced reactions out of the womxn, and through documenting their patients via drawings and photographs created a library of “medical art” that reflects images of womxn in pain or outright torture. This room holds some of those historical renderings. There’s a well-known drawing of an arched form tied to the bed, convulsing. This drawing is replicated in a sculpture in the center of the room, missing its head because, of course, what does a woman’s mind matter anyway? DiQuinzio sets this stage for us so that as we move through the rest of the more modern artwork, we have to actively remember what womxn have lived through during the preceding decades and centuries.

RELATED: Artist Leslie Holt’s series Hysterical Women

“The Pelvic Theatre Presents the History of Hysteria” by Alison Pirie

Pirie’s senior thesis is entitled, “The Pelvic Theatre Presents the History of Hysteria,” an artistic project that culminates in a series of filmed theatrical scenes, in which Pirie plays key characters in the narrative of hysteria. But the roles she takes on in these scenes are far from typical, and deliberately provocative to bring light to the wild falsehood of the roots of hysteria as a female-bound disease. Playing unorthodox roles such as the uterus and the clitoris, as well as taking on the opposing personas of the female patient and the male doctor, Pirie’s work is “empowering the female voice in this narrative and challenging the power dynamic between the historically active male physician and passive, female spectacle.” - Chapman University

“Female Remedy” by Leila Hekmat

“Many patients were sent to asylums and even received surgical hysterectomies. The notion of female hysteria, and its links to sexuality in particular, offers a lens through which to consider Los Angeles-born, Berlin-based artist Leila Hekmat’s first institutional exhibition. Female Remedy transforms the idyllic lakeside villa Haus am Waldsee into a satirical, surreal sanatorium where nurses and patients engage in debauched, erotic activities. This so-called ‘infirmary for an illness which needs no cure’, recasts the symptoms of female hysteria as positive forces, confronting the misogynistic notion that stereotypically feminine behaviours require medical attention.” - ArtReview

Infomative

Did you mention that hysteria comes from the word ‘hyster’ or womb?