Leonora Carrington Art and Mental Health

The surrealist artist's psychotic breakdown, a closer look at a specific piece of her art, and a few fun facts ...

“Art is a magic which makes the hours melt away and even days dissolve into seconds.” - Leonora Carrington

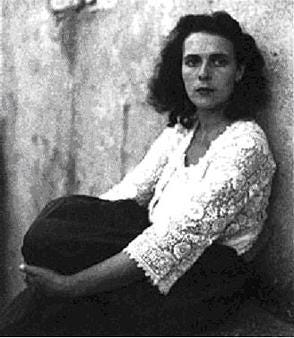

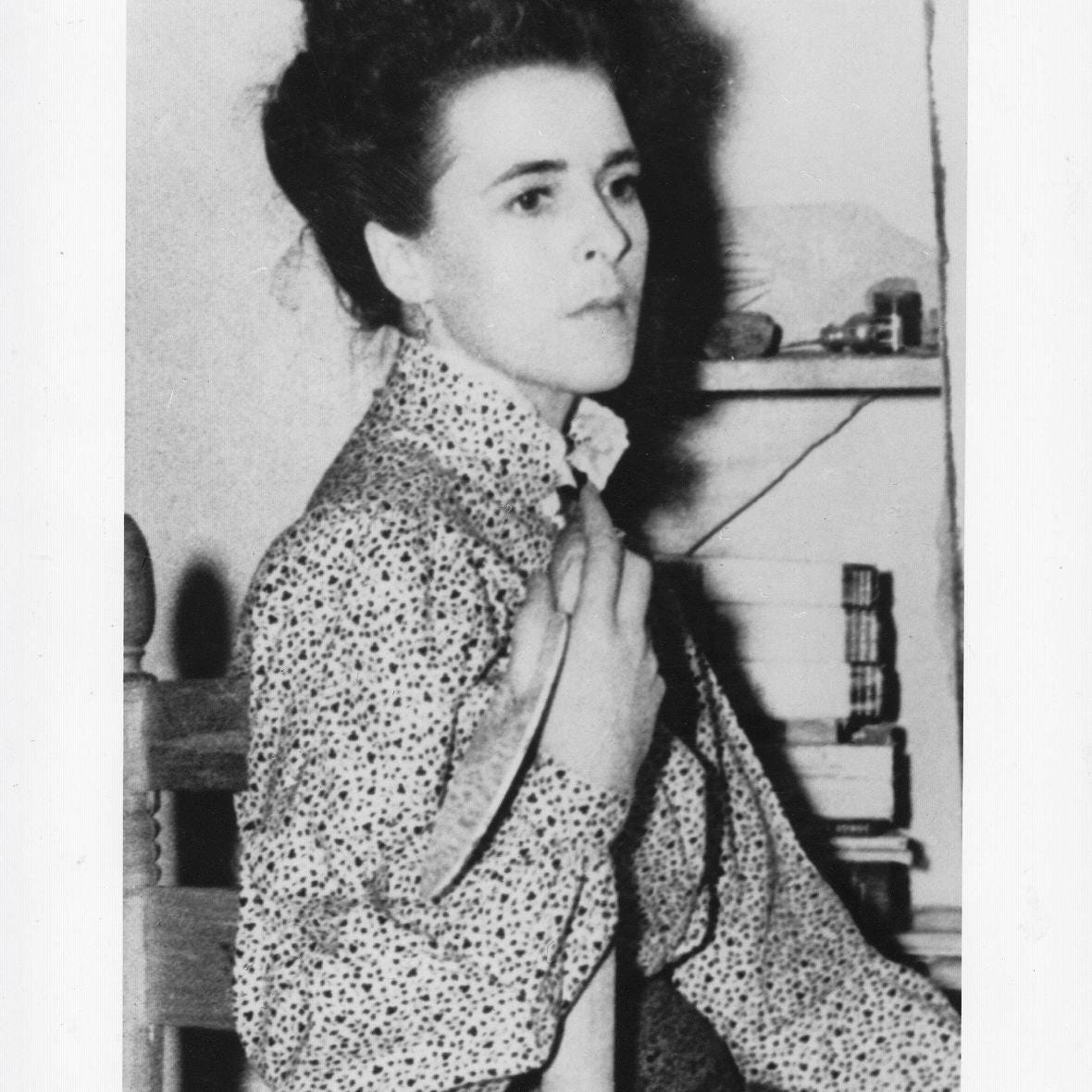

Surrealist painter and novelist Leonora Carrington’s life, art, and mental heath intersected with history in terms of the changing role of women and through the traumas of World War II. Her partner, Max Ernst, was arrested by the Nazis who interned him in a concentration camp, in large part because of his artwork. Ernst’s paintings toured in the Nazi show exemplifying “degenerate art.” Carrington, not knowing whether or not he would ever return, was left alone in their countryside home, showing the early symptoms of a breakdown.

Carrington manifested both mental and physical health symptoms, including taking on a strange limited diet and experiencing “exasperated nerves,” “an inability to walk straight,” communication with animals and nature instead of humans, and “paralyzing anguish.” Later in her life, she made it clear that this experience was indeed the direct result of trauma, writing

“I’d suffered so much when Max was taken away to the camp, I entered a catatonic state, and I was no longer suffering in an ordinary human dimension.”

Her suffering was so much that it felt beyond human.

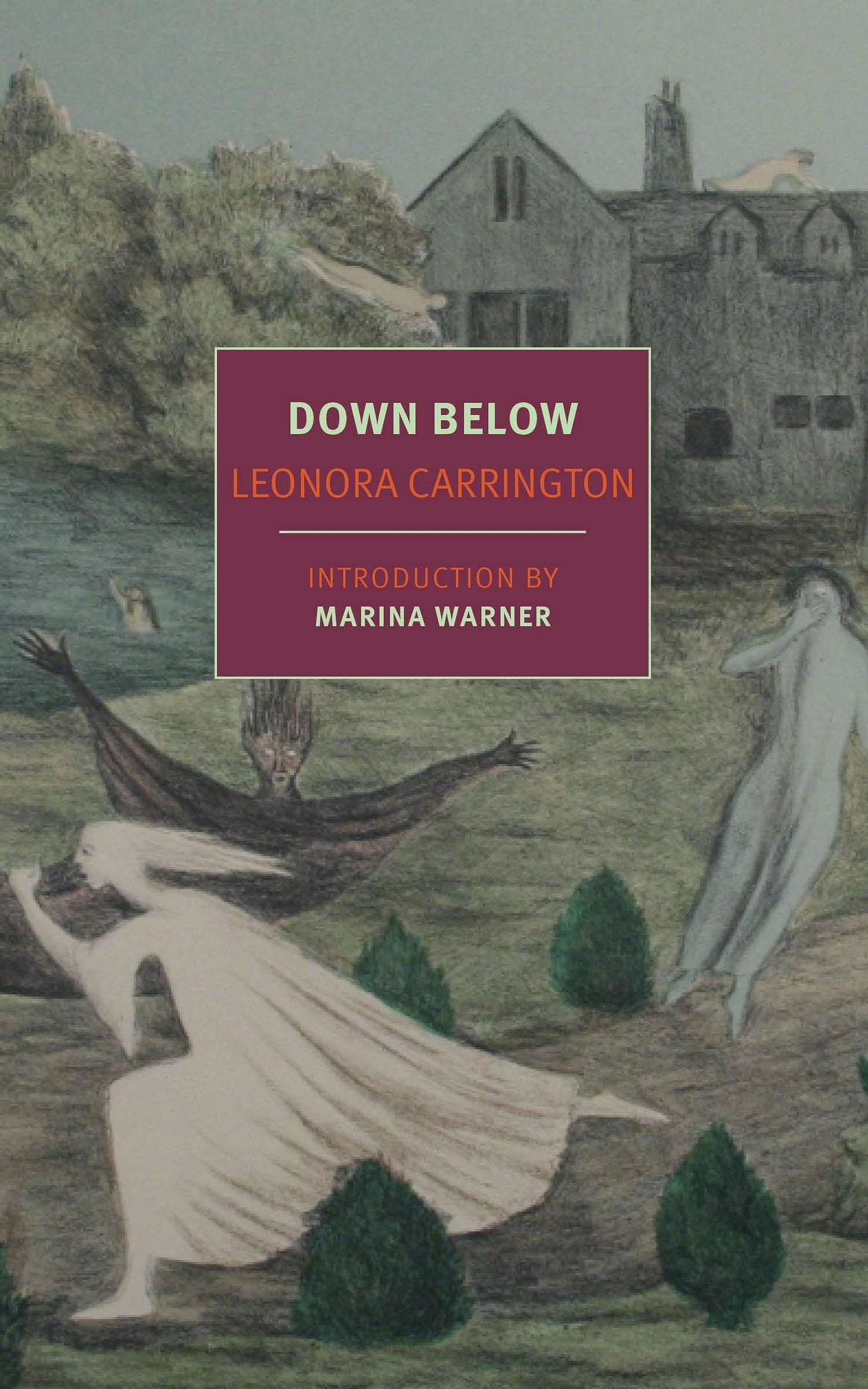

Carrington felt at times like she was various animals and at other times like she herself was the entire universe. She had always been fanciful, representing herself as different animals in her art, but this was beyond the Jungian-esque exploration of the personal and collective unconscious. She was truly unable to separate reality from delusion. As a result, she was placed in the Santander Mental Asylum - but not before one more trauma was to occur. She writes in Down Below of how, as she descended into her madness, she encountered a group of officers who kidnapped her, robbed her, and gang-raped her, afterwards abandoning her in a park.

Down Below is best known for its description of the terrible treatment she experienced in institutionalization. In the asylum, Carrington was given barbiturates as well as cardiazol. An alternative to electroshock therapy, this was a drug that induced horrifying seizures. It was a common treatment believed to help cure people of psychosis. A psychiatric review of the drug describes it as inducing “seizures strong enough to fracture vertebrae and stop the heart.” Carrington’s physical heart didn’t stop but the torture of the asylum certainly hurt her metaphorical heart.

In addition to medication-induced seizures, Carrington recalls “hallucinating naked and strapped to a bed, as she lay in her own feces,” and describes feeling in the asylum as though she were dead. Like Frida Kahlo, she was force-fed while she was there. And she hated being watched through the glass. One of the most horrifying “treatments” she was forced to endure was that doctors induced abscesses in her thighs specifically to prevent her from walking. Between that and the barbiturates, she was effectively immobilized.

Carrington’s mental health did ultimately improve, but it is unclear whether that was because of, or in spite of, her treatment in the asylum. She did describe that the experience brought her “clarity and power of mind,” and attributes at least some of her recovery to a specific doctor named Etchevarria. But for her, the journey to health was a horrific one. We can presume from her descriptions in Down Below, which was only written after she had left the asylum, that she was not permitted to create art while in treatment. Had she been allowed to write and draw and paint, would it have helped her work through the trauma? What amazing work might she have brought into the world if she painted during that direct experience? Or perhaps she couldn’t have created at this time even if given the right to do so; we will never know.

We almost always think of mental illness, particularly when it includes psychosis and delusions, as a lifelong struggle for the individual. In some instances, though, a person has a single, specific breakdown, emerges from it, and doesn’t suffer from such issues again. The rest of Carrington’s life was apparently unmarked by mental health challenges. This is why, although some have tried to posthumously diagnose her as schizophrenic, she doesn’t meet the criteria for the diagnosis. Although Carrington would never experience another breakdown, she never forgot the terror of the experience, and always feared that it could happen again.

Writing and making visual art about her experience certainly seemed to be therapeutic for Carrington as she grappled with her early trauma. For Carrington, the breakdown was a breakthrough and perhaps her art was what helped that to happen. As a surrealist artist, she “was able to imbue domestic objects and processes with value, and power.” She could view life through a lens that was bigger than just the tangible, that incorporated the personal and collective unconscious, metaphor and mythology. Although she couldn’t create art in the asylum, she used this ability while there to mentally impose structure on the chaos of the place, even though she was “always clear that the structures she imposes on the asylum while incarcerated are delusional: there is no system, and the inmates are no less sane than their keepers.”

In addition to her memoir, she also has a 1940 painting called Down Below, in which she and a white horse (also representative of herself) are in a dark garden approaching inmate asylums (who are also, of course, representations of parts of her.) This piece is the one created closest to the time that she was in the asylum.

If you read this far, perhaps you like the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

Art for Thought: Samhain Skin

Let’s take a closer look at Samhain Skin, a 1975 piece that Carrington created using gouache on vellum. Vellum, if you’re not quite familiar with it, is the skin of an animal that has been prepared for painting or writing on. This piece exaggerates the original source of the material by using vellum shaped like the body of a lamb. Most of her art is so dramatically painted with references to strange creatures; in this case, preserving “the shape of the lamb from which it was flayed” and using that as the surface is hauntingly powerful enough.

Samhain is a Celtic festival, held at the same time as Halloween, is one of the quarterly “fire festivals” that land between the equinoxes. This one marks the end of summer and the ushering in of the darker part of the year. One of the underlying beliefs of this celebration is that it’s a time of year when the boundaries between the physical and spirit worlds blur, and one can more easily move back and forth between them. This must have felt so powerful for Carrington, who had always identified so strongly with animals and the nature and spirit worlds. The Celts believed that ancestors who had already died could cross back to come capture those still living, so the living would dress as monsters and animals to trick their ancestors and not get captured. All of the various animals and masks and half-human creatures in Carrington’s other work make infinitely more sense when considered through the lens of her Celtic heritage, passed down to her through stories from her grandmother.

Her grandmother had taught her that they were descended from Sidhe, a Celtic fairy race of angels that were cast down from heaven and now come to sow seeds of trouble during Samhain. The animals, creatures and other imagery on Samhain Skin were references to these ancestors. The creatures painted at the edge of the piece have garlic atop them; as an adult in Mexico Carrington used garlic and other kitchen supplies to study alchemy, the occult, and the arts. Therefore, it’s a reference to Surrealism itself, particularly her friendship with Remedios Varo with whom she practiced these arts, as well as to the ancient past in her family. She was exploring the realm of women’s magic.

This piece is clearly dominated by a strong female influence, from her grandmother’s stories to her witchcraft studies with another female Surrealist artist. “Goddess imagery, domestic references, and reverse-handwritten Celtic terms create dense layers of symbols and meaning.” She was a fan of the book The White Goddess, which looks at early goddess-dominated religions predating patriarchal Christianity and Judaism. Samhain Skin was created decades after the rape trauma and all of those struggles she had with men who may have felt like father figures. The biological father with whom she had so much trouble was a textile producer, and she has used a textile as the basis of this piece, but one which is directly drawn from nature and the feminine side of her heritage. This female-centric piece may represent the journey she’s taken back to herself, to wholeness and health as an adult woman.

The piece is from 1975 and she was very aware of the women’s rights movement. Some suggest that this piece is a guide to help the women in the movement trace their power back to its source in order to regain it. Alternatively, or additionally, the piece could be seen “as a self-portrait that demarcates Carrington’s transition into maturity, which is later personified by the crones who populate her paintings of the 1980s.”

Of course, Carrington had incorporated many of the references from nature, and sometimes directly from this personal history, in her other work. For example, she often depicted birds in her work. Her Portrait of Max Ernst is half-bird. But this work feels decidedly different - a continuation and growth of those themes but presented in entirely new ways due both to the direct references to Samhain and to the choice of material. A bird does appear in this painting, but it is a tiny bird, and it sits next to Macha, a Cetlic goddess of the crow. Has Ernst … his power, his father figure role, his maleness … shrunk to a tiny place in her narrative while the power of the female has come to dominate her healthy adult mind?

Leonora Carrington’s mind is no doubt a fascinating place. But how much can we connect her art and her mental health? She had one very serious breakdown, during which time it appears that she didn’t have much or any opportunity to paint. She did represent that time with the painting Down Below, which appears to be the work created closest to her period of institutionalization. She wrote the memoir shortly thereafter. This seems to have been a cathartic experience for her. Perhaps by taking the story of all that happened to her - her childhood, the rape, the instituionalization - and putting it into her own voice, she performed a sort of alchemy that allowed the trauma to move through her. She would continue to paint for decades, creating works like Samhain Skin. So perhaps she created out of a mentally healthy aspect of her psychology? We can only surmise and intuit. Like this painting and so many others, there is a lot to decode and she didn’t necessarily expect people to be able to grasp the exactitude of what she was portraying.

Four Fun Facts About Leonora Carrington

1. Carrington was inspired by Remedios Varo and Kati Horna. When all three met, they had close romantic relationships with male artists (Ernst, surrealist poet Benjamin Peret, and Robert Capa respectively.) However, all of them later ended up in Mexico, each with supportive, but not particularly artistic, men as companions.

2. On one hand, Carrington’s book Down Below is used to understand the horrific asylum treatment that some have experienced. On the other hand, because she was a Surrealist Artist, many professionals and researchers dismissed the legitimacy of her claims of horror as output from her fantastical imagination.

3. Carrington actively rejected the idea that she was a muse to the men around her, saying, “I didn’t have time to be a muse. I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” Carrington also once recounted a time for a biographer when artist Joan Miro gave her money to go buy cigarettes for him and, “undaunted,” she handed the money back to him and told him to get them himself.

4. People have said that Carrington physically resembles Virginia Woolf, who is, of course, another woman famous as much for her mental health as for her writing.

This post was part of The Artist’s Mind virtual book tour.

This is an edited selection of the book’s chapter on Leonora Carrington. Following that are two pieces of the original manuscript that didn’t make it into final publication: a closer look at one specific piece of art (Samhain Skin) and four “fun facts”.

I had no knowledge of Carrington until now, and you did such a fantastic job of explaining her mental illness episode and her artistic expressions. Amazing stuff!

Love Carrington so much!