Isa Genzken: A Half Century of Prolific, Innovative Art and Openness on Bipolar Symptoms

“She has always courted danger, with predictable results—the life force and the death wish are at odds in her.” - Judith Thurman on Isa Genzken

“I always wanted to have the courage to do totally crazy, impossible, and also wrong things.” -Isa Genzken

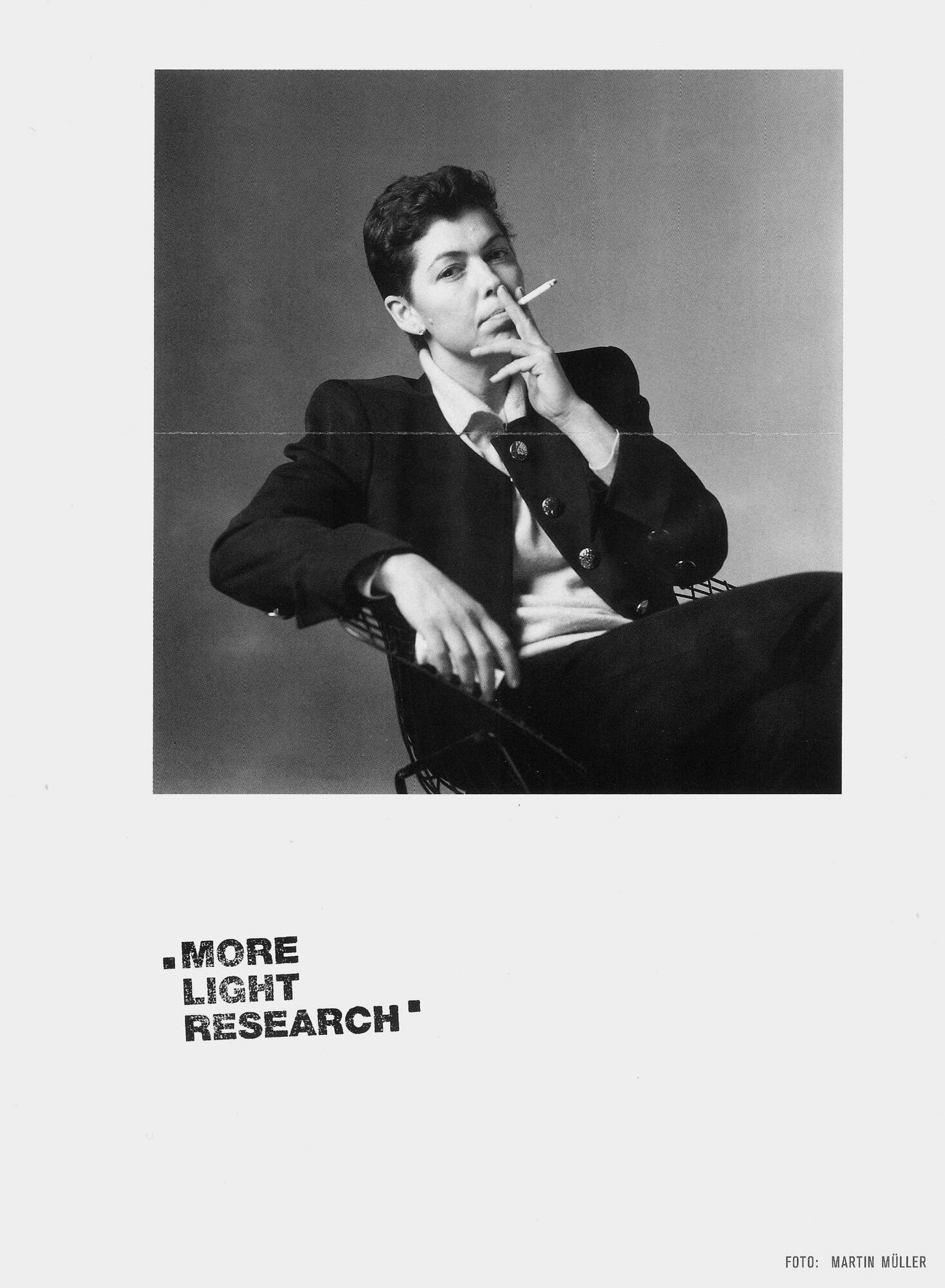

Isa Genzken is notorious for not giving many interviews about her work or her personal life. Despite that, she has been transparent with the interested public about her diagnosis of bipolar depression as well as her struggles with alcohol, a transparency that began relatively recently.

Leigh Arnold, associate curator at the Nasher Sculpture Center, which awarded Genzken their 2019 laureate prize, notes that Genzken’s bipolar disorder went unrecognized for years because the symptoms may have been less pronounced but also masked by drug and alcohol problems.

Indeed, bipolar depression and troubles with alcohol and substance use often go hand-in-hand. The exact link isn’t entirely known, but comorbidity of the two is high, higher than alcoholism among people with unipolar depression. Theories about the relationship include that people drink to self-medicate their bipolar symptoms, that the withdrawal from alcohol triggers brain chemistry to crave drinking, that it’s part of the recklessness of mania, or, more likely, that there’s a complex bi-directional relationship between the two that is so nuanced that we can’t quite understand where one ends and the other begins.

While the alcoholism was more visible, the bipolar depression was always there. Writer Judith Thurman says of Genzken,

“She has always courted danger, with predictable results—the life force and the death wish are at odds in her.”

While this is not a direct statement about the artist’s illness, it is a solid description of bipolar disorder, with its periods of manic exhilaration offset by spells of dark depression. This reference is far from the only one that people have made to the artist putting herself in danger. Curator Sabine Breitwieser notes that Genzken, “takes a lot of risks and puts herself in extreme situations in her art as well as in her life,” a description similar to characterizations of Diane Arbus.

Genzken’s work has always been cutting-edge and unique to her own vision, a vision that changes dramatically from series to series, and which she expresses through multiple mediums including assemblage, sculpture, photography, and film. She once told art collector Brigitte Detker that when someone was in her studio and saw her installation she couldn’t stand that they went away again and she would have to immediately change the installation to make it more her own. In staying true to her own ever-changing voice, she has been lauded for consistently producing fresh, new work, unique not only from what else is in the market but also from what she herself has produced in the past. One example of this is her inclusion in the opening exhibit at the New Museum; all of the other artists were emerging artists and she was well-established but her vision was so fresh that her work was welcomed.

Genzken’s first series to gain her recognition as an artist (after an early foray into photography and film that her peers appreciated) was a set of 10’ - 30’ long wooden ellipsoids and hyperboloids; lengthy pencil-like structures that touch the ground only at the center point (for the former) or the two ends (for the latter.) Realizing that she couldn’t achieve the shape that she wanted working only by hand, she enlisted the aid of a computer engineer to assist her in creating the work, providing all of the direction herself but having him create the code. This was one of the first, if not the first, recognized times when an artist used computers for their work - long before the days when computers were accessible to the average person.

From that series, she switched to concrete sculptures, often informed by urban architecture. The early concrete pieces in particular referenced the rebuilding of Germany after World War II. Born there just after the war ended, she didn’t experience the war itself, but she internalized the trauma in its aftermath. Thurman writes that “the epic reconstruction … of Germany’s rubble and of its guilt—was the unstable scaffolding of her childhood.” She put this experience into her work, not only in the concrete sculptures, but in other mediums including a film that she did of her grandparents in post-war Germany.

In addition to the complexities of life in Germany at this time, her family had to reckon with their own complexities; her grandfather was a Nazi doctor who had to answer for his war crimes; Isa once visited him in his jail cell. In her description of the memory, she recalls an open umbrella in her grandfather’s cell; umbrellas would recur as a motif in her work over the years. Importantly, the artist herself draws no connection between this history and her own work. Notably, society both in Germany and in America tended to go silent about the war in the years after it ended and so the trauma went unspoken and internalized to a degree that even those who experienced deep trauma often denied or minimized it. It is only now, generations removed, that discussions of that intergenerational trauma are beginning to take place.

In addition to the role her own family history did (or did not) play in her art, there was also her personal relationship with her husband. Genzken met her husband, Gerhard Richter, in art school where he was her professor, and he played a critical role in assisting her in getting into her first shows. It was his second marriage and he would go on to have a third with another student. They were married for eleven years, much of which was competitive, tumultuous, and intense, reminiscent of many other artists’ relationships (Georgia O’Keeffe with Alfred Stieglitz for one example.) When they divorced, she struggled to separate her identity from his, not just as a wife, but as an artist. Her worst struggles with alcoholism occurred in the wake of the divorce; at times she would binge on alcohol, living on the streets.

Although Genzken hasn’t spoken widely about her bipolar diagnosis, she has been forthright about it, particularly in this last quarter of her four decade long career. Leigh Arnold was excited to go visit her in her studio in 2018, but wasn’t certain until the last minute whether or not she would get to meet the artist; the colleague / friend that was taking her to the studio let her know that Isa continues to have good days and bad days and that she wouldn’t answer their knock at the door if it was a bad day. Arnold was happy to discover that it was a good day; Genzken was actively working on new pieces.

Similarly, when Genzken had her first American retrospective in New York in 2013, no one knew for sure if she would attend; she did, but when writer Judith Thurman tried to approach to introduce herself, she was turned away by an assistant who said that the artist needed space. This was attributed primarily to her injuries from a recent fall but mental health and physical health often go hand-in-hand.

In fact, it was around the same time as the fall that Genzken quit drinking. She had been battling alcoholism since things had gotten bad with her then-husband in the 1980s. She was in and out of hospitals, including time spent in psychiatric wards. In 2013, her doctor told her that if she didn’t stop drinking, she was never going to get out of the psychiatric hospital; she quit.

The 2013 retrospective was, in part, a celebration of her 65th birthday. She has continued to create prolifically since then. (Last year was another big exhibition for her 75th birthday.) Among her fairly recent pieces is a series of mannequin-based installations called Schauspieler (Actors). She often dresses them in her own clothes and Arnold describes them as “proxies of her that she gets to send out into the world.” This is not her only version of a self-portrait; Slot Machine has her image at the top, for example. The film Little Bus Stop is a series of acting scenes, throughout which she is drunk, and in one scene she specifically plays someone with depression. Moreover, one might argue that much of her work, although certainly a critique on society, has also been autobiographical. For example, art collector Erika Hoffman says that her “concrete sculptures express an unconscious fear that most people understand without knowing it.”

Interesting Fact: Visiting her studio in 2013 Ulrike Knöfel noticed an unfinished work, on the back of which Genzken had attached an obituary of Mike Kelley, “a California artist whose work often centered on the darkness of childhood. He committed suicide.” - source

Sometimes her work seems to represent her own duality. Writer Batyar Ungar-Sargon says that her work conveys “a rage that is somehow mediated through whimsy.” Another example is her trademark steel flower statues, which are simultaneously beautiful as a rose and a little bit monstrous because of their size, perhaps reflecting two sides of herself, although we can only speculate as she hasn’t said this herself.

Perhaps also representative of her duality is that for most of her life she divided her time between New York and Germany. She fell in love with New York the first time she visited as a teenager, had some of her biggest highs and lows in the city, and was there when the Twin Towers fell in 2001. She created a series of work in response to 9/11, starting with a series called Empire/Vampire, Who Kills Death and continuing several years later with Ground Zero exhibit sculptures. Interestingly, she once said of New York that she has never suffered from depression while living there (although it is known that she lived on the streets and struggled with alcoholism there.) She sees striking differences between the two cities and the art people create there; she says New York has the best art in the world whereas Berlin’s is “the most uptight and conventional” but marks herself as an exception to the latter.

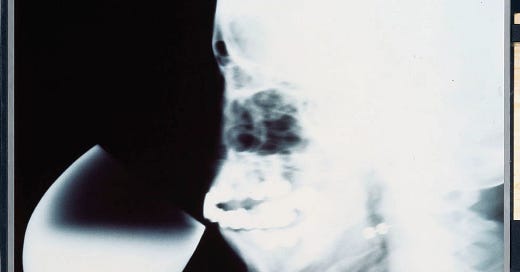

One of her most poignantly personal series is a lesser-known work in which she photographed herself in the hospital. It was a means of acknowledging the role that both her bipolar disorder and her struggles with alcohol have affected her, her body, and her image. Another strong example of how she depicted her struggles through her art is the series X-Rays, in which she has taken actual x-rays of her own head, some while drinking wine.

This work was clearly influenced by her mental health challenges, but other than this series, it’s unclear exactly how art and mental health have interacted across her life. Although her style and materials change often, there is no clear distinction indicating that the changes are relative to her diagnosis. While it’s been argued that she uses art as a “coping mechanism,” that’s not something she herself has been known to say. Gallery owner Daniel Buchholz, who represented her work for decades and played a critical role in helping her through the worst depths of her illness, says that her art is “not the result of an emotional disorder.”

We do know that she always wanted to be an artist, suggesting that she realized this about herself while she was still in the womb. In her sixties, when she got injured in that fall, she was unable to work as much as usual. For most of her career she has preferred to work alone, without assistants, and being unable to do so at this stage “tortured her.” Interestingly, her works sell for a lot of money, but she doesn’t possess a bank card and has to call a “supervisor” if she wants to spend over a certain amount of money. We can only speculate whether or not this is related to her bipolar disorder. People with this condition sometimes engage in reckless spending during hypomanic and manic states, but she has not stated explicitly a relationship between her money and her illness. In fact, although she has admitted to her bipolar disorder, she hasn’t spoken much at all about the details of what that experience is like for her. And although it’s interesting, and perhaps socially valuable, to contemplate the relationship her illness has had with her art-making as well as her art-career, we have to be careful not to make presumptions when she herself has chosen not to offer them.

Isa Genzken continues creating prolifically in her seventies. She also remains in treatment.

Genzken’s work on display in London:

“On view is a revival of Isa Genzken’s expansive installation ‘Wasserspeier and Angels’ (2004), marking 20 years since it was displayed in Genzken’s first major solo exhibition in London, UK. Originally responding to Hauser & Wirth’s former historic space in Piccadilly, London, UK in 2004, the representation of Genzken’s complex assemblage in the city brings her work into a contemporary context, confronting sociopolitical themes that are still relevant today. This moment follows on from the acclaimed exhibition ‘Isa Genzken: 75/75’ at Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, Germany in 2023, celebrating the artist’s 75th birthday with a display of 75 sculptures from her oeuvre from the 1970s to the present.” - source

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

You Might Also Like to Read:

Resources/References

Arnold, Leigh A. “The Power of Art: Creating through Disorders of the Mind.” Art and Health Series. Lecture presented at the Nasher Sculpture Center, 2019. .

Ashraf, Toby. “Film as Art and Art as Film: The Cinematic Concept in Isa Genzken’s Art Practice.” Senses of Cinema, no. 69 (December 2013).

Genzken, Isa. “Isa Genzken: Mach Dich Hübsch!” Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2105.

“Isa Genzken: Hospital (Ground Zero) (2008).” Artsy. Accessed September 29, 2020.

Kennedy, Randy. “No, It Isn’t Supposed to Be Easy.” The New York Times, 2013, sec. AR.

Knöfel, Ulrike. “MoMA Retrospective: The Strange Brilliance of Isa Genzken.” Translated by Christopher Sultan. Graham Foundation, 2013.

Perlson, Hili. “Genzken on Alcoholism and Divorce from Richter.” artnet News. artnet News, May 23, 2016.

Sonne, Susan C., and Kathleen T. Brady. “Bipolar Disorder and Alcoholism.” Alcohol Research & Health 26, no. 2 (2002): 103–8.

This Is Isa Genzken. YouTube. MoMA, 2013.

Thurman, Judith. “Isa Genzken's Beautiful Ruins.” The New Yorker, 2013.

Ungar-Sargon, Batya. “MoMa Catalog Omits Artist’s Nazi Grandfather.” Tablet Magazine. Tablet Magazine, November 21, 2013.

Wasik, Emily. “Isa Genzken, The Artist Who Doesn't Do Interviews.” Interview Magazine, May 15, 2014.