Art History and Mental Health: Surrealist Kay Sage

Do the desolation, prison-like scaffolding, and muted colors of Sage's dreamscapes reflect a history of depression?

Visually, surrealism has always captured my attention. And yet, in writing about artists with mental health challenges, I’ve rarely delved into the work of the surrealists. One exception is a chapter on Leonora Carrington in my book The Artist’s Mind: The Creative Lives and Mental Health of Famous Artists.

I think perhaps I’ve stayed away from the surrealists so far because THERE IS SO MUCH THERE THERE.

Surrealism itself, as a creative movement and a philosophy, is deeply linked with mental health. The two cannot be separated, starting with the way that the surrealists were influenced by Freud’s interpretation of dreams. This aligns with my personal beliefs that we are all artists and all have mental health. But it doesn’t make for ease of studying the mental health of Surrealist artists, particularly in terms of their art’s content. So, I think I’ve stayed away for a long time because it’s daunting, and I don’t know where to begin. But you have to begin somewhere, so I’m going to start today with a dive into the work and life of Surrealist Painter and Poet Kay Sage. I’ll do the best I can … and perhaps I’ll end up having to come back to this eventually when I keep learning more. But that’s okay. My work is a body of work not a single article.

Why Start With Kay Sage?

Perhaps all humans are artists and all have mental health challenges … but in some this is more obvious than others (both the art and the mental health.) When it’s obvious - when someone whose career as an artist has known mental health challenges - it makes it at least a little easier to observe and draw conclusions. Kay Sage, whose work productivity sharply declined due to depression and who died by suicide, is one of these artists.

Also, I actually don’t know her work well at all which gives me a fresh starting point as opposed to with artists I already have lots of preconceived ideas about. So, we start here.

Who Is Kay Sage?

Kay Sage was a surrealist artist, primarily a painter of works that are highly architectural. In later years, she was known more for her poetry. She was born in New York just before the turn of the 19th century to a state senator and his wife; the wife left the senator and raised Kay and her older sister mostly in Europe. Perhaps this unusual start in life (women divorcing their wealthy husbands then was not common, of course) contributed to her unconventional approach to life and art over time. She, too, would leave her first husband (who happened to be a prince) after a seemingly content but purposeless decade she described as years she "threw away to the crows. No reason, no purpose, nothing."

Much of her biography - creatively and personally - is devoted to the fifteen years that she was married to Surrealist painter Yves Tanguy, whose work received better reception than hers at the time - true, of course, for many women in creative relationships throughout history. Sometimes these relationships are truly relevant to an artist’s work and mental health; sometimes they aren’t. In Kay’s case, their creative work influenced one another; they pushed each other but it was also complex and as Karen Rosenberg of the New York Times puts it, “may also have been artistically suffocating.” But more especially, her relationship with Tanguy was known to be emotionally volatile, and his death seemed to lead directly to her depressive decline, which impacted her art.

In terms of the biographical stuff about her art, she started showing her own Surrealist work in the late 1930’s, although she was never fully accepted by the Surrealists as “one of them”. The bulk of her most well known work was done during her marriage to Tanguy, which lasted from 1940 to the mid-fifties, at which time he died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage. They had a passionate, troubled relationship that’s been argued to have been impacted by her moods, his alcohol consumption, infidelity, verbal and perhaps physical abuse.

Life with Tanguy might have been hard at times, but his death devastated her, and upon it, she fell into a deep depression. She began painting less and less, due at least as much to the symptoms of depression as to her failing eyesight. However, the creative urge was strong, and it was at this time that she began to write a lot of poetry and to work on collage/assemblage art. This may have helped her cope but it didn’t save her life. There was a suicide attempt in 1959, and although she continued creating art and life for another few years, she did die by suicide in 1963.

What We Know About Kay Sage’s Mental Health

Many sources report that Kay Sage experienced depression, that her artwork declined as a direct result of this depression, and that the content of her artwork often reflects this depression. I’m going to dig into what people have said to this end. But before I do, I offer the note that mental health is a really personal, unique thing, and Kay Sage was reportedly a really private person who didn’t share her thoughts on her own mental health widely. She did write an unpublished autobiography called China Eggs that I’m not sure it’s possible to find excerpts of (tell me if you know anything about this!) So at some point she did think about sharing her story and thoughts. But she didn’t do so much … So this is all speculative.

Some have suggested signs of mood disorders early in her life. Hinting at this, Gelly Gryntaki over at The Collector writes: “Kay Sage had an unquiet mind, seeking shelter in artistic creation.” Interpretations of her decision to leave her prince husband suggest that she was devoted to art for the benefit of her own mental health over the comfort of the relationship and all of the formality that went with such a life.

Many have drawn interpretations about her relationship with Tanguy and how that impacted/ intertwined with her own mental health and affected her art. Gryntaki again: “Tanguy was her strange attractor: a force fatal and creative at the same time.” And also notes that a war was going on in the world at the same time as the difficulties in the marriage, so perhaps it was both personal and broader that her paintings became increasingly representative of “despair.”

Again, this is speculative. But essentially, most sources agree that she went through a period of deep depression following her husband’s death, due not only to loneliness and loss but also to her declining vision and the impact that had on her ability to paint.

According to Brittanica:

“Her growing blindness made her fear that she would not be able to paint again, a fear reflected in her work of that time, such as The Answer Is No (1958), whose subject is numerous blank canvasses and empty easels.”

[Note: this is not historically uncommon, growing blindness linked to an artist’s depression has been noted in Edgar Degas and Claude Monet, among others. This interests me, of course, because it reflects the important intersection of art and mental health. And shows, too, that we can’t really separate mental and physical health.]

Perhaps painting helped Sage through life and when she couldn’t paint anymore, it was devastating for her. She turned to poetry, and she wrote several collections in the French language, but it seemingly didn’t do for her cathartically what painting did for her. Or maybe it did, for a time, but ultimately art couldn’t save her life. Perhaps it is both as simple and as complicated that living without her husband, aging in body and mind, was too hard. Perhaps she idealized a life beyond death that was better, easier, more complete, more … something … Reportedly, her suicide note included:

“The first painting by Yves that I saw before I knew him, was called ‘I’m Waiting for You.’ I’ve come. Now he’s waiting for me again – I’m on my way.”

Kay Sage’s Art and Mental Health

The short description of The Answer Is No above is a powerful one in regards to art and mental health - blank canvasses and empty easels being obvious expressions of a lack of creativity or an emptiness of creative thought. We’ll look at some of her other paintings through the mental health lens.

But first, an overall view of her work …the color and composition of her architectural dreamscapes have often been suggested to represent depression, reflecting a dystopian view of society. Gryntaki uses the phrase “sad cartographies of a strange world” and adds poignantly: “Placid anxiety and a feeling like pacing towards a nightmare, but not reaching it. There are peaceful seas and ghostly shipwrecks, lunar sceneries, and obscure humanoid shapes, all in plain light … it’s deeper than pure melancholy or gloomy apathy, rather an indiscernible sense of vulnerability and risk.”

Alexander Adams explains how Sage’s work is often a depiction of frozen, barren, dry, excessively ordered landscapes populated with half-formed structures. And says, “There is a touch of depressive paralysis to the art – that sense that change is both impossible and futile.” And adds … “Sage’s palette was drab, exploiting the emotional muteness of earth colours, half-tones and greys. … Psychological research shows that individuals experiencing clinical depression are less receptive to colour than non-depressives are and Sage’s muted palette seems indicative of psychological numbness and isolation.”

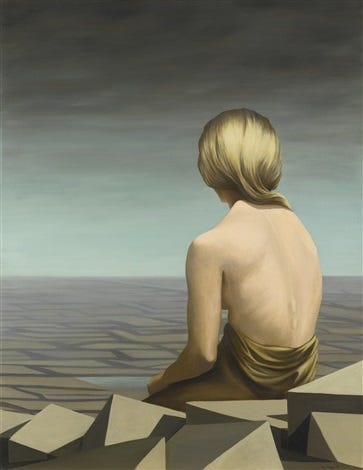

Le Passage

This is personally my favorite of her paintings, although it is strikingly different from most of her work. Most of her work is architectural, although set in the sort of dreamscape that we think of when we think of surrealism. This one is of a woman, one of her only paintings with a figure in it, shown from the back, posture slumped, staring out at an arguably bleak rocky landscape. To me, perhaps because of the figure, perhaps because of knowing how unhappy she seemed to be at the stage of life when she painted it, this one looks most obviously representative of depression in its content and tone. Its emotional content is easy for me to access because it looks so familiar to my own experiences of depression.

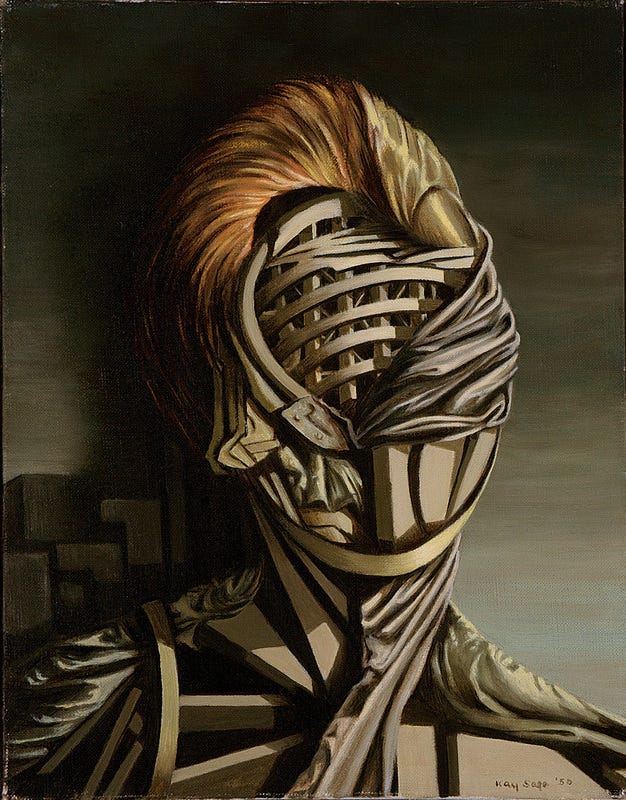

Small Portrait

This is one of the only other paintings featuring a person, and it is such a powerful image. It is a human but also it is not. There are no facial features. The whole head is architectural beams and fabric drapery. It has the effect of depicting a human mind that is cluttered and imprisoned.

Verna Valencia writes about how scaffolding is a theme throughout Kay’s work and how we see it here. She means the lattice work, the architectural beams, the lines. However, scaffolding also has a psychological meaning. It comes from Vygostsky’s theory of the Zone Of Proximal Development in learning … basically, in order to learn, you need to be pushed slightly out of your comfort zone … scaffolding is support that your teacher provides for you to get there and then withdraws because you don’t need the support anymore. They provide the scaffold. Therapists do this as well. At a basic level, they provide you with a support system and validation until you’ve set that up for yourself in your personal world … but they also do it at many stages in many ways throughout the process of therapy.

Knowing this, the painting intrigues me. What scaffolding do we need in order to cope with our own minds, our own identity?

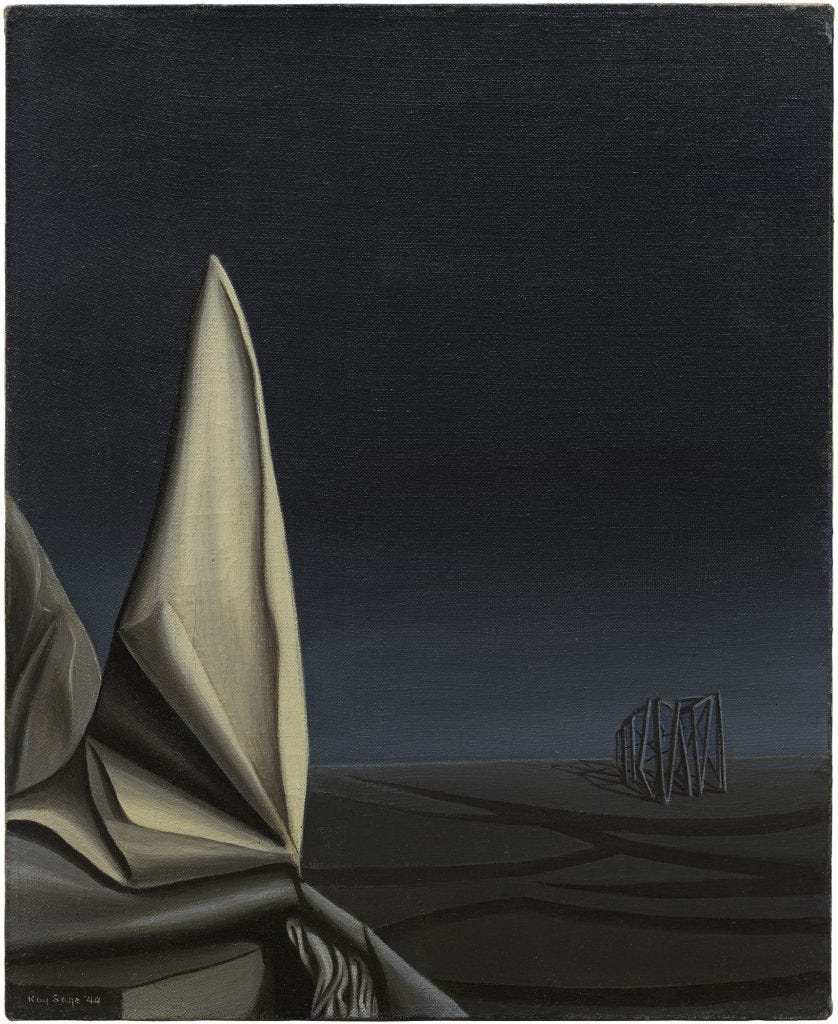

Tomorrow Is Never

This is one of Sage’s most well known works, a piece created shortly after Tanguy’s death, after a period of not creating at all, during a time when she was clearly dealing with grief-turned-depression. Many people have written about this work and its relationship to her psychology but I think The Metropolitan Museum of Art summed it up best:

“Like many Surrealists, she used landscape imagery as a metaphor for the mind and psychological systems of being. Rendered in somber grey tones, “Tomorrow is Never” combines motifs in the later stages of her career, including architectural scaffolding, lattice-work structures and draped figures to evoke feelings of entrapment and dislocation.”

Somber grey … scaffolding … entrapment and dislocation. In addition to these words of description, people have used:

“subdued light with shreds of cloud or fog” (Alexander Adams)

“vast, desolate background” … “buildings half-built, abandoned, and vulnerable — to portray Sage’s feelings of isolation and loneliness” (Erin S.)

“a sense of being closed in and a loss of orientation” (SCHIRN)

“Her latticed structures rise from insubstantial bases of swirling mist in a melancholy monochrome” (Howard Devree, New York Times, according to biographer Judith Suther)

Margin of Silence

Sketchline says:

“The object depicted on the canvas is figurative and static; even the drape looks heavy and frozen. The dark background and the blue-violet fabric, enveloping the foreground figure, hints at the feeling of anxiety in the one whose face the viewer does not see. The poetic names of many works by Kay Sage, including this one, only reinforce the mood of psychological devastation, expressed by the combination of geometric and soft forms, as if this is the last relic left by the civilization in barren landscapes.”

Midnight Street

SFMOMA shares an important thought here:

“Midnight Street suggests a desolate dream, and it is tempting to read loneliness into the work. Indeed, Sage began to paint in this way only after the deaths of her father and her sister in the early 1930s and her later divorce. However, the emptiness of Midnight Street might also convey Sage’s fierce independence. Her personal writings reveal a resolve for privacy.”

Important as a reminder that we can make a lot of interpretations about the way Sage’s work represents her psychological state … but we ultimately don’t know. SFMOMA also notes: “Kay Sage was not inclined to explain her paintings. When asked about one of her works, she famously said that she knew “nothing of [its] origin except that I painted it.”

Kay Sage and Poetry

Sage’s poetry was perhaps a way of continuing to paint when she could no longer see to paint. Gryntaki says, “If her paintings have titles that sound like poetry, her poetry could describe images she never had made. There are empty rooms with more than one colored door, blackbirds, ivory towers, and blood-stained aprons.”

Collage and Assemblage

Although she couldn’t continue painting in the same way. Kay Sage did persist in creating visual work to the end of her life. Elisabeth F. Sherman writing for the Whitney Museum of American Art describes the catalog the artist created for her final exhibition in 1961, a work of art itself incorporating images of the pieces in the exhibit along with one of her related poems, something she seems to have paid as much detail to as the work itself. Sherman notes that the collage pieces required the text of poetry because Sage was “aware, however, the assemblages failed to capture the same complexity of ideas and depth of imagery as her paintings.”

China Egg

As aforementioned, Sage authored an unpublished autobiography titled China Egg. Gryntaki notes how the egg was a recurring theme in Sage’s art, representative of her or a part of her that is fragile and vulnerable, lonely and isolated, “showing a prison of life and creativity that can hatch or be disparaged by predators.” Sherman notes that the work covers only her childhood up to her sister’s death in 1934, so perhaps it doesn’t offer specific insight into her own mental health, and it obviously doesn’t cover her mature years with (then without) Tanguy. But since it apparently is told through two voices and covers topics like the inconsistency of memory, I assume that there’s some richness there to be uncovered in terms of her own mind. If I find a copy, I’ll delve in.

Some of my thoughts …

It is believed that she was creatively stifled during her first marriage. What comes to mind is a scene from the TV show Scandal in which the president’s wife, Mellie, is inanely choosing china patterns when she would rather herself be running the world. It’s one picture of a thousand pictures of a million women across time. We don’t know if she was depressed during this time but she was at the least in a creative drought. Perhaps the boredom made it impossible for her to create and she had to get out of the boredom before she could make art. Or perhaps making art was all that helped her from losing her mind to the boredom and so she turned to it wholeheartedly. Both things have been true for me - when life was so empty because of depression, I couldn’t create and I had to create.

The deaths of others seems to be tied up in her making. It was after losing her sister and father that she began to create actively. It was after losing Tanguy that she stopped creating as much. Loss and grief are very close to depression (notably different, but with similarities, and one can become the other.) What comes to mind is how one writer, Leon, responded to a note of mine today saying in part: “I think part of it is because we fear death. Not the physical death, but the death that comes when our name is spoken for the last time ever. We long for something that lives beyond the small time we have on this planet.” Death, loss, they impel us to create. And also they can freeze us for a time. In Sage’s case, she didn’t paint for about six months after Tanguy’s death … then she created Tomorrow is Never, one of her most famous paintings.

One of the things that interests me is how mental health challenges change our creative content, process, medium, productivity. It is widely accepted that Sage went into deep depression after Tanguy’s death if not before. This is also tied up with her failing eyesight. Mental and physical health aren’t separate. In my own life, my father coped with lifelong untreated depression and “work” (woodworking, writing) was what helped him most get through each day. As he got older and it became harder and harder to do those things, his work changed (smaller scale woodworking, for example, and he adapted) but maintaining a healthy mindset got harder, too. He lost a finger in a woodworking accident and he was never the same after … physically he could still work but mentally it meant something devastating to him and he never quite mentally recovered. Without as much passion for the work, with a lot more hopelessness and pointlessness seeping in, his desire to keep creating was strong but his feelings of not-worth-it were often stronger. We don’t know why Sage died by suicide but we know she had vision loss and depression …. these things changed her medium (from large scale painting to assemblage and poetry), her content (my favorite of her works, Le Passage, is one of the only paintings that has a figure in it), and her productivity (which declined greatly in those later years.) We don’t know why she chose death but I am drawn to a quote of hers as explanation: "I have said all that I have to say. There is nothing left for me to do but scream."

People have had a lot to say about the muted tones of her work, the barren landscapes, and how they might reflect depression. I don’t disagree … or agree … I am still mulling this one. I know that I’m drawn to them and that Le Passage feels like depression visualized for me because depression is loneliness among many other things that it is.

I suppose what I am trying to express here is that my two cents, my interpretation, my narrative that I place over her story (which may or may not be accurate) is that Kay Sage was compelled to create, that creating gave her life meaning and purpose and excitement, and that when it came to the end of her life and she felt her ability to create slipping away from her (because her creative partnership with Tanguy was done, because depression was eating away at her mind, because her vision was failing and surgery didn’t help) she didn’t see a reason to keep on keeping on. Creating was her purpose and without it she saw no purpose. Perhaps.

What do you see in Sage’s work as it relates to mental health? What resonates for you or doesn’t?

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

You Might Also Like to Read:

Source Note: I wasn’t able to find any books about or by Kay Sage through my library, so I’m looking for those online now and hope to eventually add to my understanding of her through that reading. I’d really like to get a copy of Judith Suther’s biography of her but so far the most inexpensive one I’ve found online is $80. So we’ll see. The online sources that I utilized for this initial exploration of Sage’s art and mental health are linked throughout this article. If you’re interested in her story, I recommend diving into those links!