The creativity and depression spectrum: behind the scenes of The Artist’s Mind

A guest post by Kathryn Vercillo on the relationship between mental health and art.

The relationship between mental health and art — or any creative pursuit — is an area of interest for me, as I picked up the paintbrush at a particularly tumultuous time in my life. Art has been a tool for healing for me, and also, sometimes, a source of mental distress. Perhaps that is why Vincent Van Gogh is one of my patron saints — an artist whose work and life I reference to navigate both the highs and lows of the creative life.

Today, I’m sharing a guest post by whose work focuses on the complex topic of how art/creativity interacts with mental health/wellness/psychology, with the aim of helping artists with mental health challenges to thrive creatively, financially, and psychologically.

This post is part of a month-long virtual book tour for her latest book, The Artist’s Mind: The Creative Lives and Mental Health of Famous Artists. Yesterday, the tour stopped for a book review from Samantha Rose McRae of I Have Thoughts. One of Kathryn’s favorite posts by Samantha is I Have Depression, which is particularly relevant to today’s guest post.

The Creativity and Depression Spectrum: Behind the Scenes of The Artist’s Mind

I find it helpful to use spectrums as frameworks for many things. For example, I believe that we’re all on a mental health spectrum and we’re all on a creativity spectrum. The intersection of those spectrums for each individual fascinates me. So, it’s no surprise that I am one of the people who looks at the depression spectrum, rather than “depression” as a diagnosis. How creativity relates to mental health can differ greatly along this spectrum.

The depression spectrum refers to the different types of depression diagnosis one might receive. At one end is unipolar depression, where you’ll find persistent depressive disorder and major depression, the things people usually mean when they say “depression.” That’s my own diagnosis and so the experience I understand best. At the other end is bipolar depression, which co-exists with the mania of bipolar experiences. And in the middle are variations on these - postpartum depression, cyclothymia, and others.

In writing The Artist’s Mind, a book of short biographies exploring the mental health of famous artists and the way it affected their work, I went back and forth about how to present the depression spectrum disorders. There were a lot of artists in this category, as opposed to say a category related to schizophrenia, and I didn’t want to overload the chapter but I also wanted to give it its due attention. I debated a lot about whether to put depression and bipolar as two separate parts of the book for that reason.

There’s a great case to be made for separating them, the biggest of which is that the artists who experience hypomania or mania in bipolar often find that to be a really fertile creative time whereas people with depression don’t have that experience. There’s also a case to be made for not separating them, the biggest of which is that some artists, especially from much longer ago in history, may have received an incorrect diagnosis of depression when they were elsewhere on the depression spectrum.

As a writer, I considered this carefully, but ultimately, I chose to keep the depression spectrum together as one section of the book, even though that makes it a lot longer than the other sections. I did this because I really do believe in the depression spectrum model rather than the historic binary approach to the two conditions, and I couldn’t see myself separating them out just to make the book a little neater and more even.

The one big drawback to this is that I did have to filter out some artists that I’d intended to include so that Part 1 didn’t become even longer than it already is. Depression, along with anxiety, is one of the most prevalent mental health conditions. It’s also less stigmatized than some other conditions, and it has been spoken about publicly for much longer. As a result, there are not only more artists with depression than with other conditions, but also more information about those artists and their mental health. I worked to create a balanced perspective across history, incorporating different gender, race, orientation and other points of intersectionality within the limited list of artists that my publisher and I had already settled on.

And then within that I also tried to include diversity along the depression spectrum. Alice Neel and Mark Rothko both experienced life-threatening depression. Edvard Munch and Diane Arbus likely had bipolar depression. Joan Miro is usually described as having depression but it’s been argued that it was cyclothymia - which essentially has lows that aren’t quite as low as life-threatening depression and highs that don’t rise so high as to be manic. Georgia O’Keeffe had depression in combination with anxiety, although is considered “high-functioning” in both categories.

The thing about diagnosis is that it’s a useful tool for many things and then once you have the tool you might want to throw it out because it also has its limitations. The tool is useful in the context of this book because it gives us a sense of the artist’s experience and a starting point for a conversation about how their mental health relates to their creativity.

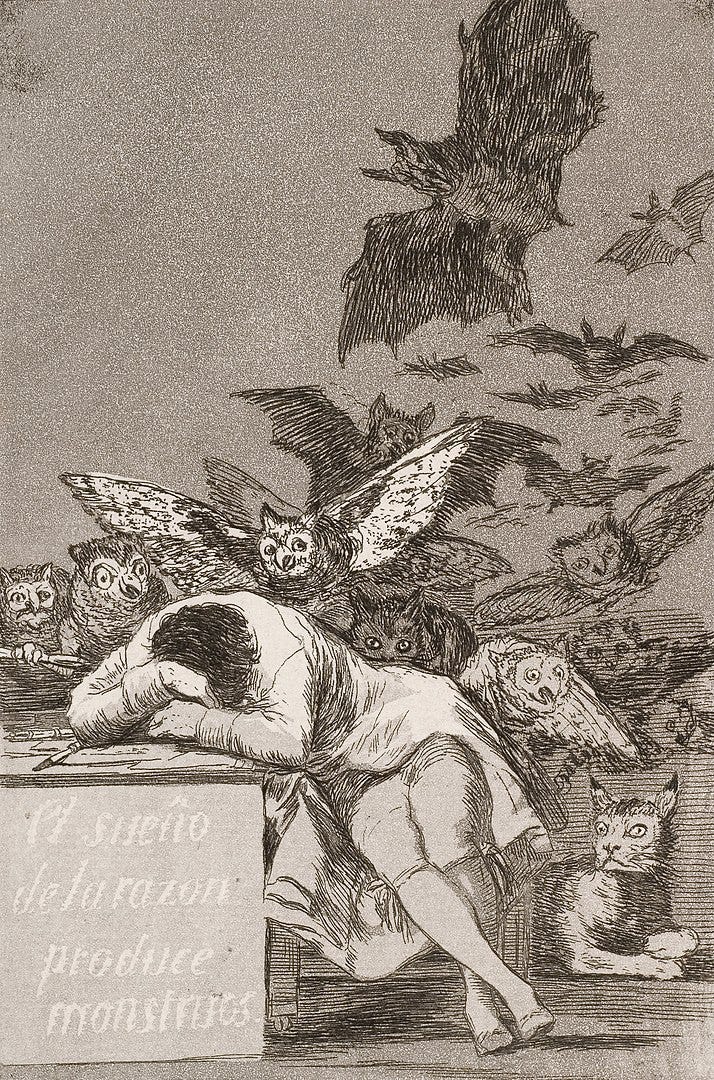

For example, Goya lived with depression that was exacerbated by self-imposed isolation — something that gave him the opportunity to really delve into a fantasy world of dark thoughts that come through in some of his most powerful emotional work. That’s a good place to begin talking about whether art was therapeutic for him or exacerbated his depression. The artist himself felt that his mental health and creative self derived from the same place so he couldn’t have one without the other. And we see in his personal history that depression for him was likely caused by or tied to a physical health issue as well as to global trauma that impacted his experience of life.

As you can probably surmise, none of this is simple … I wanted to share the stories of these artists with attention to their diagnosis and yet without limiting our understanding of them to this diagnosis. I wanted to share as many versions of depression experience as possible among the artists while choosing artists diverse in other ways as well. But more than anything, I wanted to start a conversation that asks:

In what ways does art help people living with mental health challenges?

In what ways might creating art, or making a living from art, exacerbate mental health symptoms?

In what ways do mental health symptoms affect an artist’s creative process, content, medium, and productivity?

As someone with depression, creativity has often been healing for me. I write to understand my mind and receive cathartic release. I crochet to bring my mind and body to a meditative space where I can heal. And yet, as someone with depression, I also find that my symptoms sometimes make it impossible to create: fatigue, brain fog, trouble with concentration, low self-esteem, hopelessness … these all make it so that I can’t always write or crochet or create when I would like to. I’m still puzzling through how this all balances out for me, how to accept all of it but also maximize the benefits of creativity I want while maintaining holistic wellness. And I hope that this book begins a conversation that assists other working artists in achieving that same thing for themselves.

I hope you enjoyed reading Kathryn’s thought process behind writing The Artist’s Mind. One of the things that I found interesting was her explanation of the depression spectrum, which makes it more inclusive and holistic, I think. There’s also hope in realizing that there are a whole plethora of artists who continued to create through the fog and the isolation and the debilitating effects of their mental health struggles. It makes us feel a little less lonely, I think, and a little more hopeful that we can create beauty and make meaning despite our struggles.

Don’t forget to stop at the next stop on the virtual tour, which you can find on the schedule here. You can follow the whole tour and Kathryn’s continuing research in this area by signing up for her Substack.