By Guest Contributor Kathryn Vercillo

This is a guest post by Kathryn Vercillo, author of The Artist’s Mind: The Creative Lives and Mental Health of Famous Artists. It is part of her month-long virtual book tour where she shares behind-the-scenes and bonus info including other guest posts, interviews, excerpts and more. You can find all of the stops on the tour here.

The Artist’s Mind is a book of short biographies of well-known painters and sculptors throughout history who also dealt with mental health challenges. It explores the complex relationship between art and mental health, with the goal of starting a deeper conversation in society around the nuances of this relationship. It looks at ways art was therapeutic for some of these artists, ways it might have exacerbated mental health problems, and ways that mental health impacted their creative content or process.

I am a writer because I am a reader. Although the act of writing feels as critical to my life as the act of breathing, reading runs even more deeply through me. It is in many ways my heartbeat.

So, researching through reading is one of my favorite parts of writing. I read dozens of books during the research phase of writing The Artist’s Mind. Many of them were helpful. Nearly all of them were interesting. But here are the five that really stood out as critical to making the book come to life:

Frida Kahlo: Song of Herself by Salomon Grimberg

There are countless books out there about Mexican artist and painter Frida Kahlo. But this one is a goldmine when it comes specifically to her mental health. Most books don’t even address her mental health, especially not with specific detail as to how it was intertwined with her creativity. In contrast, that’s what this entire book is really all about.

The book, written by the psychiatrist Salomon Grimberg, is based on an interview the artist did with a psychologist friend about the creative process. So, it draws from Kahlo’s own thoughts about creativity, shared warmly and openly with a friend, through the lens of psychology and then psychiatry. This really created an amazing framework for understanding the different ways of looking at the relationship between art and mental health within the context of Kahlo’s life.

By extension, it helped me look at this relationship for other artists as well. In other words, it allowed me to take something I read about a different artist and try to apply this lens to it. Because this book is an easy read, it was really helpful at times when I got stuck writing The Artist’s Mind.

Women on the Verge: The Culture of Neurasthenia in Nineteenth-Century America

One of the things that I had to reckon with when writing this book was the way that mental health diagnosis has changed over time. I felt that it was important to explore some of this history, because the way society views mental health ties into the way that we view artists and creativity.

Our view of mental health informs how we treat the severely mentally ill, such as those living in asylums. We see in The Artist’s Mind that some artists were allowed/encouraged to paint/draw while institutionalized whereas others were not allowed to; this affected them greatly and related to how person-centered the treatments were at the time.

This book was helpful because it provided a close look at neurasthenia, a historic diagnosis that was only around in society for a very short period of time. Neurasthenia was understood as a condition not entirely dissimilar to depression in that the symptoms included trouble sleeping and eating, physical aches and pains, and listlessness. However, it was specifically diagnosed in relation to the belief that “the harsh conditions of modern industrial society had generated new nervous disorders.”

More often than not, it was applied to women, who were then encouraged to go on total bed rest and were sometimes not even allowed to feed themselves. They certainly weren’t encouraged to read or create art.

Arguably, this “rest cure” was more harmful than helpful to their mental health. While I didn’t incorporate a lot of this book’s specific details into my own book, it gave me a solid understanding of how the state of society, and the way that plays out in regards to how we treat specific sections of that society, relates to individual mental health. This is something that informed a lot of the underlying philosophy of my own book. I tried to add context when sharing about each artist, looking at the impacts of war and racism and sexism and poverty and so forth as it all relates to mental health and creativity.

The Discovery of the Art of the Insane by John MacGregor

Whereas the book about neurasthenia gave me a concise lens for that type of exploration, this book provided a much more comprehensive look at the topic. In fact, this book is so dense that I think I’d have to read it a dozen more times before I really soaked it all in. It takes a long lens at the history of mental health and how we as a society have treated those considered “mentally ill.”

It is a mental health history. But it’s told through the very specific lens of the art created by those described as “insane.” MacGregor shares a variety of artists throughout history, some educated in art and others not at all, who created art while deeply mired in mental health challenges. The book further explores how that art helped us understand mental illness (and also how our understanding of the artists was limited by our understanding of mental illness at the time they created).

It also looks at how the art created by these people, and the way that it has been interpreted then and since by art historians and psychiatrists, influenced the development of modern art. As I said, it’s a dense book - not just in terms of extensive content but in terms of the intellectual approach it takes. The beauty though is that it served as an encyclopedia of ideas for me as I worked on The Artist’s Mind.

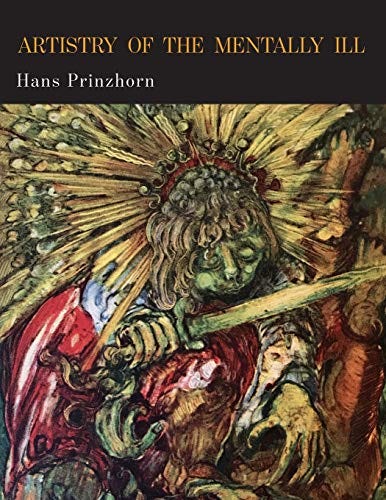

Artistry of the Mentally Ill by Hans Prinzhorn

This is one of the books that you pretty much have to read if you are going to study the relationship between art and mental health. It’s like reading Freud if you are going to study psychology. There are many theories and revelations that come after Freud, including plenty that discredit Freud’s work, but in order to really understand the evolution of psychology, you have to study Freud at some point. And that’s how I feel about Prinzhorn’s book.

It was written almost one hundred years ago; it’s in the public domain. Prinzhorn collected art from people who lived in asylums. He studied that art to find clues as to why we as humans create, identifying six drives such as “the urge to play” and “the need for symbols.” This really gave us a language for understanding the psychological motivations behind creativity.

Moreover, because he was particularly interested in the kind of mental health issues that would fall into a description of schizophrenia today, he gave us some insight and understanding into this specific condition as it relates to society. Other artists decades later used his findings to further explore their own art.

Prinzhorn is considered a forerunner in “discovering outsider art” - a problematic term and practice but one that’s been historically relevant to the discussion of art and mental health. So, this was a foundational text for me particularly for the background it delivered for writing the section on artists with schizophrenia and “outsider art” in the book.

Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and The Artistic Temperament by Kay Redfield Jamison

I first read this book in my late teens, more than two decades ago, which reflects how long I’ve been interested in the relationship between art and mental health. I remember at the time feeling really intrigued by Jamison’s description of bipolar creativity and how much it differed from the lens of “mental illness is a bad thing to experience” which was so much of the narrative back then and remains part of the narrative today. Because of Jamison’s work and those like her, though, we as a society have started to understand, at least a little bit, that it’s more complicated than that.

There are some really challenging things about living with bipolar, of course, but there are also some beautiful things about this kind of mind, and Jamison celebrates that in an honest, detailed way. In this book, she looks at famous creatives like Van Gogh and Virginia Woolf to explore the role of bipolar experiences in their creativity without giving into tropes about the “mad genius.” This aligns with, and perhaps helped me initially form, my thoughts about how mental health challenges are not necessarily “bad” or “good” for art but are just realistically going to impact the how and why of creativity so it’s worth digging deep to understand that impact.

The Artist’s Mind is just the beginning of the conversation that I am interested in having about the nuances of how mental health and creativity are entangled with one another. You can stay on top of my newest writing and research into this topic by signing up for my newsletter at Create Me Free.