When Dickens stepped in to keep me company: How reading literature gave me purpose during a time of grief

A Create Me Free guest post by Jeffrey Streeter

Today I have a guest post for you from

of . I’ve shared his work with you here before, in this roundup:One of the things I’ve written about often is the power of experiencing art. Making art is cathartic but simply experiencing art can also be extremely healing (or conversely, potentially traumatizing). We sometimes forget this when we watch tv or listen to podcasts or even read books. But then a work will grab us by the shoulders and shake us or hug us and we remember that the reason we make art is not only for us but for the others who may experience it. So, I am happy to be able to share this guest post with you about reading Dickens to deal with grief.

When Dickens stepped in to keep me company

How reading literature gave me purpose during a time of grief

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” You half expect any essay about Dickens to start with the celebrated opening of The Tale of Two Cities. But to be honest, only the second half of that phrase seemed true in November 2021, when my brother called to tell me about my mother’s accident. The opening of Dickens’ novel goes on: “It was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair,” but again, it seemed only half true at that time.

My mother had “had a fall,” as they say, and a bad one. Somehow, she’d fractured both her hips, something the doctors at the local hospital had rarely seen. She was just about to turn 88 and had a weak heart. It was touch and go whether she’d survive the operation.

I was working in Hong Kong at that time, and my mother was in England. Hong Kong had weathered the pandemic pretty well until then (things were to change drastically in early 2022), but at great cost to freedom of travel into the city. I’d only just made it back to Hong Kong after attending my father’s funeral in February 2020, before the city effectively closed its borders. Those restrictions remained, and if I left now to visit my mother, I probably wouldn’t get back in. There was a strong risk I’d lose my job and be separated for an indefinite period from my immediate family.

I was thus in a quandary. Leave or stay? I discussed it with my brother, and we decided that I’d stay—for now. But we both knew—without either of us saying anything—that if things got worse, I’d get on that plane anyway.

My mother’s operation took place during the night in Hong Kong. It was perhaps the longest night of my life. I went to bed, but without any thought of sleep. I checked my phone every five minutes for news—there was none for hours—as I lay there, desperately hoping my mother would pull through. I felt utterly helpless. And completely lost.

It was then that I thought of reading Dickens. All fifteen of his novels, which have an average length of around 700 pages.

I’d had the experience of reading through grief for my father in 2020 and 2021, as in the spring of each of those years I’d sat on the balcony overlooking Victoria Harbour reading Louise Glück’s Collected Poems. I don’t know why I’d turned to Glück. There was no special connection between her and my father, who didn’t read poetry and who’d probably never heard of her. But the connections came as I read her beautiful meditations and observations, with images of loss, grief, her father, and burning fields (my father had been a farmer), all moving me in ways I could hardly understand.

But why Dickens now, as I lay shattered by worry as my mother’s life hung in the balance? The connection was slender. My mother, like my father, was born in Portsmouth. And Dickens was the most famous English person born in that naval port. That was all. But it was enough.

In 2016, I read all of Shakespeare’s works during his anniversary year, which at first felt almost like a duty but turned into one of the most joyful and richest experiences of my life. I would do the same with Dickens, I thought, and it would be something to sustain me, regardless of the outcome of my mother’s operation.

My mother survived. My longest night finally came to an end, and I downloaded Dickens’ complete novels onto my Kindle. I had no way of knowing when I would be in the right state of mind to begin reading them, but I would be amply prepared when I felt more at ease and ready for the task. After 8 hours, which of course felt like 8 days, I felt relieved when I heard the encouraging news from England; my mother’s operation had been a success, though she’d need special help to learn to walk again. Relief flooded in and lifted me like a ship in dry dock.

The days passed, and my mother was transferred to a local NHS nursing home that gave her all the care she needed. Within a week or so, I was even able to briefly talk to her.

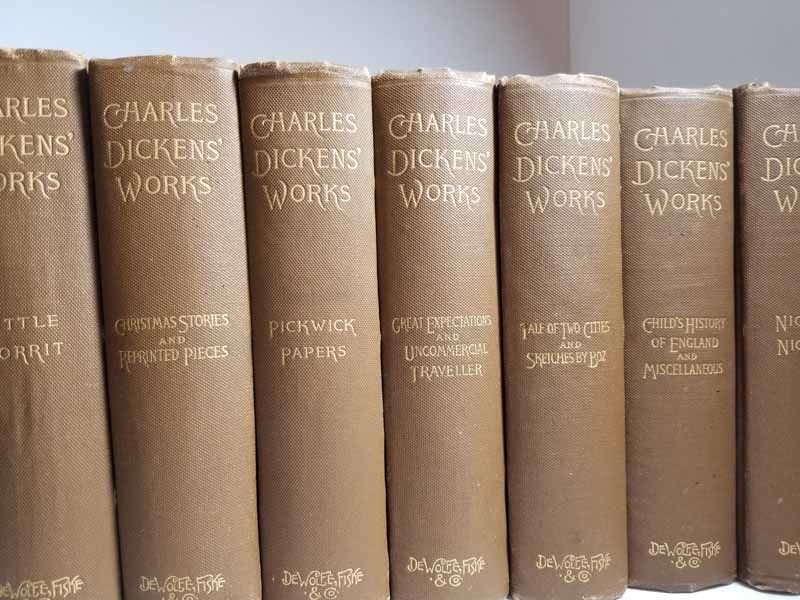

As the days and then weeks went by, as my mother regained her strength and some of her mobility, Dickens kept me company through The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickelby. My mother impressed the care staff with a bravery and resilience I could also recognise in Dickens’ strongest characters, such as Mrs Bagnet from Bleak House.

When I sat reading Nicholas Nickleby, it was as if Dickens was trying to celebrate with me how strong my mother was. The account of Nicholas’s journey to Portsmouth in that novel, the only trip to that city in any of his novels, struck me as especially auspicious:

“Onward they kept, with steady purpose, and entered at length upon a wide and spacious tract of downs, with every variety of little hill and plain to change their verdant surface.”

Dickens was describing the South Downs, the chalky hills that straddle across the southern part of England and that separate London from Portsmouth. My mother had grown up in constant view of their uncannily pale contours. It was a landscape I’d first seen while visiting my grandparents with my own parents as a child. Somehow, this brought me as close to her as I could get at a time of pandemic travel restrictions. I almost felt like I was reading my way to her.

And as I continued to read and my mother continued to recover, I realised that Dickens was part of my recovery. Partly, it was because of the connection I’d formed in my mind between him and my mother during that dark night. Partly, it was the fact that I had something on which to focus my mind—a positive displacement activity, if you like. But there was something else. Reading a particular author’s works one after another gives you a special feel for their writing. And I connected with Dickens’ pulsating buoyancy, his forward momentum, and the life-affirming panache in his style, which lifted me and carried me in its wake.

When April came, my mother was already getting out of the house on her mobility scooter. Not yet half-way through my reading of Dickens, I successfully negotiated my final departure from Hong Kong (and my career) for the summer of the year so that I could return to England and care for her.

The NHS (the most popular of British institutions) and her own courage had saved my mother. And my mother’s inspiring bravery, along with the writing of Britain’s most celebrated novelist and Portsmouth’s favourite son, had saved me from despair. No, it was more than that; Dickens’ all-encompassing prose was transporting me to a happier place. I chose to see this as a stealthy gift from my mother, for whom her six sons’ happiness had always come first.

At last, the winter of despair had finished, and the spring of hope had arrived.

About Jeffrey Streeter

Jeffrey Streeter grew up in the English countryside but has lived mostly in large cities around the world. In 2022, he stepped back from full-time work and dedicated himself to writing and reading. He publishes the English Republic of Letters, which focuses on literature and the role of language in our lives. He also enjoys going to the ballet, cooking, and appreciating the passage of the seasons in Japan, where he currently lives. He finished his reading of Dickens' novels in March 2023.

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

“I connected with Dickens’ pulsating buoyancy, his forward momentum, and the life-affirming panache in his style, which lifted me and carried me in its wake.” Wonderfully realized, Jeffrey.

I read all of Shakespeare's works last year and am reading Steinbeck's works this year. It is a fascinating experience to read through an author and have them keep you company for a time. I have read a few of Dicken's works but not all of them. Love the way the literature is intertwined with life.