The Complicated Family Dynamics in the Life and Work of Diane Arbus

Daughter and mother, possibly the lover of her own brother, what role did family secrets and fuzzy boundaries play in the photographer's art?

This is how art and health intersect for a famous artist. If you are interested in understanding this relationship in your own life: Order a Creative Health Assessment or Book a 1:1 Coaching Call.

So far, looking at the complex relationship of art and health in the life of photographer Diane Arbus, I’ve shared an overview of what I covered in my book chapter about her along with some of the material that didn’t make it from the first draft into the finished chapter. And then I shared a deeper look at one of her specific photographs: Woman on a Park Bench on a Sunny Day. Today, I want to return to the book chapter that I wrote and the discussion of Diane Arbus’s sexuality. More specifically, I want to turn to the way that fuzzy boundaries in her family of origin might have potentially impacted her mental health and her art.

In Lubow’s 2016 biography, he revealed the shocking confession that Diane had not only likely had an incestuous relationship with her brother when she was a child, but that they had resumed the affair as adults, having sex with one another as recently as just a few weeks before her death. We can only guess at the sexual trauma and unhealthy dynamics that may have been at play in that relationship, what might have caused that to occur in the first place, what impact it might have had upon her psyche.

Reportedly, as a child “Diane masturbated in the bathroom with the blinds up, to insure that people across the street could watch her, and as an adult she sat next to the patrons of porno cinemas, in the dark, and gave them a helping hand.” This phrase comes from Anthony Lane in The New Yorker. There’s much to unpack there, and mostly it’s stuff that’s all up for speculation. There’s a lot that we simply don’t know. We don’t know what her family thought about her masturbation or if they shamed her for it in any way but although Lane shares a story that her father once caught her brother masturbating and said he’d murder him if he ever caught him doing that again. We don’t know why she was masturbating for the neighbors to see; it’s tempting to pathologize this, particularly in light of the stories about incest in the family, but we don’t know for sure what motivated young Diane in this way. And I’m not sure about juxtaposing that action with the adult action she takes at the adult movie houses, if indeed the reports of that are true, since adult actions are read quite differently than children’s. We don’t know whether that was consensual activity among adults or really any of the circumstances around it. Lane also says in the same essay: “She once said that she had sex with any man who asked for it, and described a pool party at which she worked through the various men, one after the next, as if they were canapés.” This is, mostly, a continued example of what I mentioned in the previous essay - Arbus has often been oversimplified particularly in terms of harsh judgments about her sexuality.

And yet … if it is true that she was masturbating for the neighbors as a child, that she had an incestuous relationship with her brother as both a child and as an adult, it’s something that certainly plays a role in her identity, which relates, inextricably, to both her mental health and her creativity. Of course, this could be a chicken-and-egg thing as it regards mental health. If she were bipolar (which may or may not be the case, as previously discussed), then the hypersexuality could be an expression of that. If she were molested or otherwise had sexuality placed on her at a young age, this might have contributed to her experience of depression and numbness. We don’t know. Lane acknowledges this in The New Yorker piece, although he puts the onus on Arbus:

“Are we dealing with verifiable facts here, or with a yarn entwined with myth and spun by a woman in distress? Either way, what stands out is the tone of Arbus’s telling. The intimate rapport of brother and sister was apparently recounted to the psychiatrist in a casual manner, as though incest were no big deal—just a family habit that you kept up, like charades. And that otherworldly coolness drifts into Arbus’s art. What her admirers respond to is not so much the gallery of grotesques as her reluctance to be wowed or cowed by them, still less to censure them or to set them up for mockery. She makes Fellini, a more urbane soul, look a little hot in the blood. Freaks may abound in her art, but not once do they freak her out.”

Sexuality is complicated to define, and I don’t want to pigeonhole hers, particularly in regards to the choices she made as an adult. What I do feel comfortable saying is that if these stories about her family of origin are true, then there was, at the very least, an extreme lack of boundaries. Often, when one doesn’t learn boundaries in their childhood home, it becomes difficult to embody them later on. This could speak to Diane’s attitude towards sexual relationships, which Alex Mar says, “...contributed to the instability of her life, confused some of her friendships (both social and professional), and possibly made her sick.”

I find myself curious about her relationship with husband Allan Arbus. Lubow, in a WSJ article, writes:

“That word seductive is often applied to Diane, and it’s a pretty good word for her,” observed Pati Hill, one of Arbus’s intimates. When she was only 13 (and still Diane Nemerov), she bewitched Allan, a penniless young man who had come to work in the advertising department of Russeks Fifth Avenue, the large women’s department store owned by her family. Overriding her parents’ objections, Diane married him when she turned 18.”

I take issue with the Lolita-esque description of a 13 year old seducing anyone. From my calculations, Allan was 18 at the time. Yes, it was a different era. I haven’t found writing that questions this relationship; most refers to them as high school sweethearts. But she was still a thirteen year old girl. I have questions. Should there have been different boundaries in place?

Diane remained married to her daughters’ father, Allan Arbus, although they separated, and neither reportedly considered monogamy a requirement of marriage anyway. While still married, she started seeing artist Marvin Israel who was also married. About a decade into their marriage, at least according to Lubow, Israe; began sleeping with her adult daughter Doon. While this appears to be consensual and reportedly didn’t begin until Doon was an adult, it does speak to continued fuzzy boundaries in the family.

Alex Mar, writing for The Cut, depicts the relationship between mother and daughter as a strong and positive one although the example given could raise eyebrows:

“In stark contrast to her own mother, Diane, to the best of her ability, was devoted to her children. Her daughter Doon would later describe how she and her mother would dare each other to rush up to total strangers in Central Park and try to get a rise out of them. It comes off like a kid’s-play version of Diane's work.”

After Arbus’s death, Doon became Arbus’s estate administrator by default. She seems to have worked hard to protect her mother’s legacy - and also at times, her secrets, a legacy that Israel has assisted her with at times. Sabine Heinlein writing for Tablet, describes the biography that Doon co-authored about her mother as thoughtful: “eclectic assemblage, its circumspect selection of material, and its simple and elegant design pay tribute to a complex woman” while retaining privacy and respect.

In addition to fuzzy boundaries, the family seems to have been very bent on keeping secrets. Lane points out that she concealed her separation from the girls’ father from her parents for three years. Olivia Lane puts it in an article for The Daily Beast, “A strained family life is the obvious Freudian interpretation for Arbus’s fascination with secrecy. “We were a family of silences,” Diane’s younger sister Renee recalled. What filled them? What was so unspeakable?” Was it her experience with family secrecy that compelled her to photograph the secrets of others. As Lubow writes:

“(She spent) weeks, sometimes years, getting to know her subjects so well that they would drop their guard in her presence. If time was limited, she learned to surprise people into candor, or exhaust them into it. It wasn’t just truth she was after, but Truth. She could be devious in her efforts to produce a photograph she considered honest. “I love secrets, and I can find out anything,” she told a Newsweek reporter in 1967.”

But for another perspective on this, we have Geoff Dyer of the Guardian:

But if we locate Arbus in relation to the larger history of photography her peculiarities seem less, well… peculiar. Schultz, naturally, is alert to Arbus's obsession with secrets, especially "naughty" ones. But when she says that "I really believe there are things which nobody would see unless I photographed them" she is reaffirming the faith in the mainstream documentary vocation as expressed and embodied by Walker Evans: "It's as though there's a wonderful secret in a certain place and I can capture it. Only I, at this moment, can capture it, and only this moment and only me."

It’s probably not either/or but both/and … The experiences she had in her family made her acutely aware of secrets and gave her a fascination with them which she channeled into her art and pulled out of others, doing so in a way that was aligned with documentary photography theories. At least, that’s my two cents.

As I’ve expressed, I believe that we all exist on a mental health spectrum and we also all exist on a spectrum of creativity. It’s widely accepted that many mental health conditions are, if not genetic, then at least more likely to show up in family members as a result of circumstance. And, perhaps, artistic drive and creative talents also run in families. If so, Arbus’s family is an example here as well. Her father was a successful painter. Her brother was a poet who won a Pulitzer Prize and was named 1988’s US poet laureate. Her sister was a designer and sculptor. The lineage would continue; her daughters Doon and Amy are a writer and a photographer.

So where did Diane fit on each of those spectrums? Depression was a lifelong issue for her. She started painting at a young age although she quit and said that she hated doing it even if she did have a talent for it. Photography came into her life later but was her deep, compulsive passion. When people talk about the work that she did at the end of her life, the almost always talk about her portraits of institutionalized women. They’re remarkable, for sure. But another project she was working on in those last years is also intriguing: Family Albums.

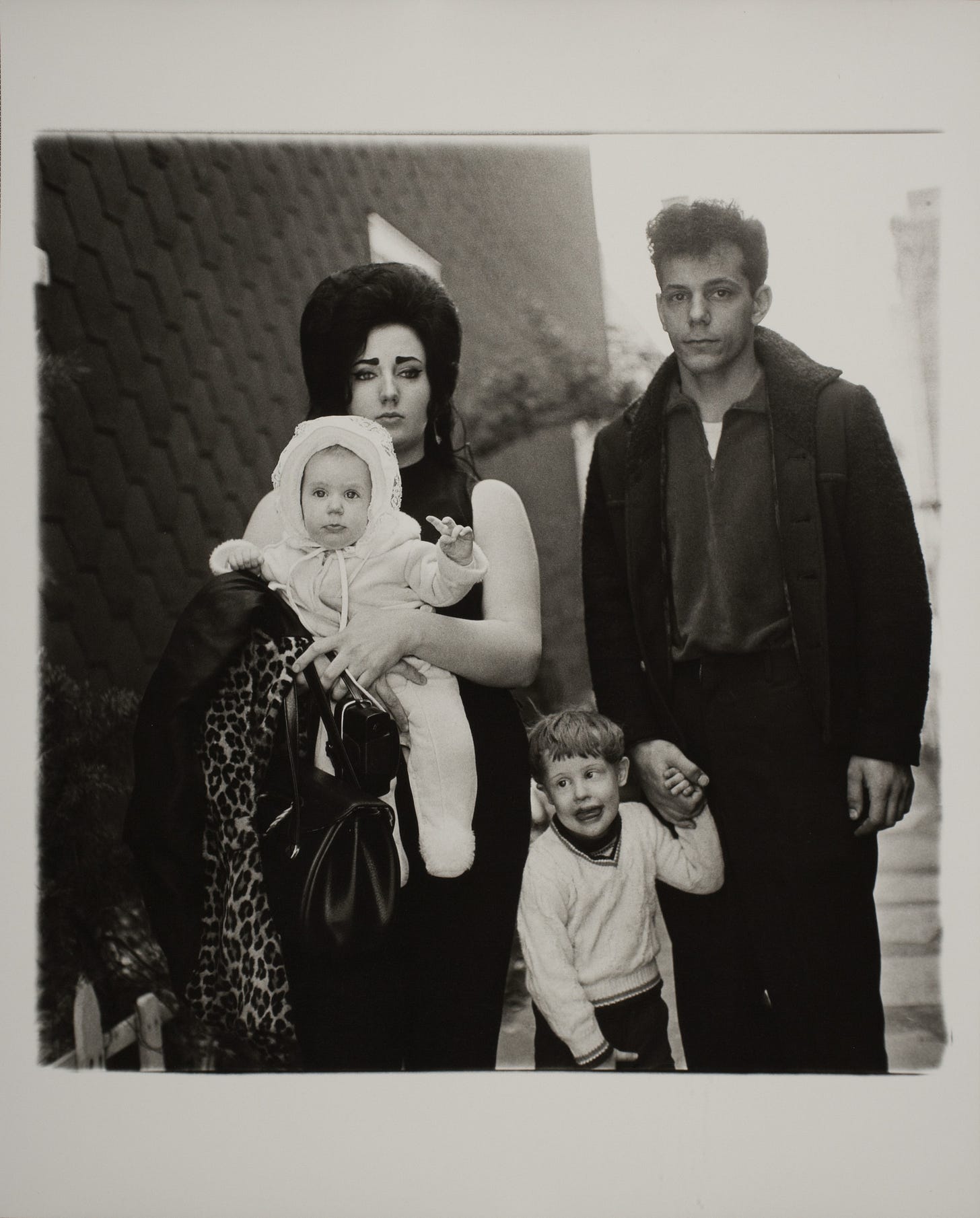

In 2004, Grey Art Gallery at New York University mounted an exhibition of her work under the name Diane Arbus: Family Albums, describing:

“What was Arbus’s documentary vision? In 1968, three years before her suicide, Arbus wrote that she was compiling her photographs into a “family album,” likening it to a “Noah’s ark” and perhaps imagining in it the people who might be remembered and saved in the aftermath of the tumultuous 1960s. “Family,” in Arbus’s sense, consisted of people held together by all sorts of bonds, some traditional and others alternative, and deserving of special attention.

This exhibition re-examines Arbus’s never-completed project and offers a glimpse into what such an album might have looked like. It assembles pictures of various kinds of families and family members and offers Arbus’s critical, sometimes humorous, often sympathetic viewing of mothers, fathers, children, and partners. In addition, it includes the contact sheets for six different portrait sessions and reveals Arbus’s working methods and selection process as she aimed to find appropriate subjects for her ark. In all, Diane Arbus: Family Albums proposes a new way to understand the concerns and goals of this most important American photographer.”

Grey Art Gallery goes on to describe how Arbus’ portraits seem to depict mothers, fathers, children, partners. The majority of the photos in the exhibition come from a commissioned project in which Arbus followed around a family for a few days, taking hundreds of photographs of their lives. What caught my interest most was that some of the most compelling images are of the family’s 11 year old daughter. 11 is cited as the age when Arbus’s mother had a nervous breakdown and Arbus experienced her own first period of depression. The portraits Arbus took of the 11 year old girl in this family are striking enough that one is the star of the introductory paragraph to an exhibit review by Michael Kimmelman for The New York Times:

“IN the photograph, the 11-year-old girl stands stiffly before a plain wall in her sleeveless, white crocheted dress, arms leaden, mouth shut. Her grave face is tightly framed by long hair and bangs, which almost conceal her eyes. She stares back at us from the shadow cast by the bangs, with a look that I might register as fear, although who is to say for sure? The heavy formality of the transaction between photographer and subject announces itself. The girl is clearly responding to the person making this portrait, whose presence we sense. By its nature the picture tells us who this photographer is. She makes sure that we know.”

Kimmelman took issue with the exhibit’s attempt to create a sense of “family” out of a collection of Arbus’ photographs. He reminds us that Arbus used the word “creepy” to apply to “all families.” And he says that the exhibit doesn’t necessarily tell us what her feelings about family are. But if his criticism is that the inclusion of a wide variety of photos under labels like “father” is too broad and not accurate to her vision, I wonder … because while it may not have quite been her vision, her experiences with fuzzy boundaries might actually be well represented by such a collection.

Richard B. Woodward, who also latches on to Arbus’ “creepy families” comment in his New York Times piece, notes:

“And yet the falseness of the categories highlights the true themes of Arbus's photographs: the bravery and fierce individualism that people are able to sustain, despite the wretchedness of their lives. She didn't lump her subjects together, but let them stand nakedly alone. Families are creepy, in Arbus's view, because they offer such an arbitrary sense of belonging. Children don't choose their parents, but the accident of consanguinity forges bizarre, everlasting bonds.”

Again, this makes me wonder about her own experience of childhood, of what it meant to her to be in a family, of how her role as daughter or sister impacted what she chose to create. We don’t know, but I find myself looking at her photographs with the question in mind.

In an article for Disability Studies Quarterly called Exceeding the Frame: The Photography of Diane Arbus, Ann Millett gives us insight into the family dynamics of one of Arbus’s “freak show” subjects: Eddie Carmel and his parents. She writes:

“Arbus shot a series of images of Carmel and his parents; the one developed into Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents in the Bronx, NY (1970) is a black and white image featuring Carmel in the center of a working class family's living room leaning on one cane, towering over and gazing down at his two comparatively miniature parents, who stare back up at him with facial expressions of awe, amazement, and perhaps a bit of fear. The grainy quality of Arbus's technique and the detail captured by her camera emphasize this non-idealistic atmosphere in an amateur style family photo. The compositional arrangement and exchange of gazes may be interpreted as an ominous family album snapshot of parents confronting the monster they have created.”

There’s much more that I hope to explore about the way families are depicted in Arbus’s work and how that may or may not relate to her own family history. However, for now, I’ll wrap up with this “fun fact” that I found interesting … Writer and activist Susan Sontag famously hated the work of Arbus, seeing it as a wealthy artist exploiting oppressed and marginalized people. This debate, about whether her art is exploitation, has raged for decades and changes with the times. And yet, the interesting part: Arbus photographed a touching image of Sontag and her son sharing a mother-child moment.