Hilma af Klint: Charting the Unseen Through Art, Spirituality, and the Psyche

Her art was primarily a "medium for spiritual communication rather than an end in itself." This is critical framing: "visions" as a unique mode of perception and spiritual engagement, not pathology.

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), Swedish artist and mystic, is now recognized as a pivotal figure whose abstract paintings are among the earliest in Western art history. Her groundbreaking work significantly predates the acknowledged abstract compositions of Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Piet Mondrian. This challenges the established, male-centric narrative of abstract art's origins and calls for a re-evaluation of art historical chronology.

Despite her pioneering contributions, af Klint's extensive body of work remained largely unseen for decades due to her explicit directive that her paintings be withheld from public view for 20 years after her death. This intentional obscurity, a deliberate choice rather than a passive state, has only recently given way to global acclaim. Exhibitions, such as the Guggenheim's "Paintings for the Future," have broken attendance and sales records, marking her posthumous ascent to international prominence. This act of withholding suggests a profound statement about the world's readiness to receive her message, implying a belief that the prevailing artistic and societal paradigms of her time were insufficient to comprehend the spiritual depth and unconventional origins of her art. This reorientation of her work's purpose, prioritizing future understanding over immediate worldly fame, offers a subtle critique of the art system's limitations during her lifetime.

Understanding af Klint's unique contribution necessitates an interdisciplinary approach, integrating insights from art history, spiritual philosophy, and psychological inquiry. Her artistic output is not merely an aesthetic exercise but a deeply integrated expression of her profound spiritual experiences and a unique psychological landscape. This report will delve into her biographical context, her deep engagement with spiritualism, the distinctive characteristics of her abstract oeuvre, and contemporary psychological interpretations of her experiences, culminating in an analysis of her belated, yet powerful, legacy.

I have developed these ideas after decades of lived experience, interview-based insights, and deep research into the complex relationship between art and health. They are based on my unique 6-part framework. If you are interested in assistance in applying these ideas to your own life: Order a Creative Health Assessment or Book a 1:1 Coaching Call.

Transmuting Grief Into Spirituality Into Creativity

Hilma af Klint was born in 1862 into an affluent, noble Swedish family with a distinguished naval lineage. Her father, a high-ranking naval officer, fostered in her a keen interest in nature and mathematics, disciplines that would profoundly influence her later artistic endeavors. This early exposure to rigorous scientific observation, alongside her subsequent spiritual pursuits, highlights a fundamental duality in her approach to understanding the world, a quest for underlying order in both the material and immaterial realms.

At the age of 19, af Klint gained admission to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, notably one of the first art schools in Europe to admit women full-time. Between 1882 and 1887, she underwent rigorous training in traditional genres, including drawing, portrait painting, botanical illustration, and landscape painting, graduating with honors. This academic foundation provided her with a strong command of empirical observation and technical skill, which she later adapted and applied to her investigations into spiritual and unseen realities.

A pivotal event in her early life was the death of her younger sister, Hermina, at the age of 10 in 1880. This profound loss significantly deepened af Klint's interest in the spiritual dimension, leading her to begin participating in séances as early as 1879, at seventeen years old. This early engagement with spiritualism, preceding her abstract work, suggests a personal quest for understanding beyond the material world, likely fueled by her grief. The experience of deep personal suffering can serve as a fundamental reorientation of creative purpose, pushing artists beyond conventional forms to seek meaning in transcendent ways. For af Klint, this personal trauma appears to have been a direct causal factor in her turn towards spiritualism and the unseen realms, which subsequently became the primary subject and method of her groundbreaking abstract art.

The Spiritual Compass: Theosophy, The Five, and Mediumistic Practice

In the late 1880s, Hilma af Klint profoundly immersed herself in spiritualism and esoteric philosophies, most notably Theosophy. Theosophy, as a movement, posits that science, art, and religion are interconnected reflections of an underlying life-form accessible through meditation, study, and experimentation. This holistic worldview profoundly shaped her artistic and spiritual development. She later joined Anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner's system, which placed a greater emphasis on artistic expression. Steiner, whom she met in 1908, also notably advised her not to release her paintings for fifty years, a directive she largely followed.

A crucial development in her spiritual and artistic journey occurred in 1896 when af Klint, alongside four other like-minded women artists (Anna Cassel, a lifelong friend from the Academy, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, and Mathilda Nilsson) formed a spiritual group known as "The Five" (De Fem). This collective was emblematic of the era's intersection between spiritual exploration and female empowerment within the context of prevailing restrictive social norms.

"The Five" engaged in structured mediumistic practices, including regular séances, meticulous documentation, and experimentation with automatic writing and drawing. They believed these practices enabled them to communicate with "High Masters" or spirit guides such as Gregor, Clemens, Amaliel, and Ananda from the astral plane. These automatic techniques were instrumental in af Klint's development of her unique visual language, allowing her to move beyond her formal academic training towards abstraction. She attributed her early revolutionary forays into abstract art to external spirit guidance rather than her conscious mind.

The 2022 film Hilma highlights that af Klint alone would not have achieved the same results without the collaborative framework of "The Five." Their structured approach, which included beginning meetings with prayer, meditation, scripture review, and then proceeding to the séance, as well as their meticulous documentation in notebooks underscore the collective and disciplined nature of their spiritual and creative work. This communal practice served as a crucial enabler of radical abstraction. While the "mad genius" trope often emphasizes solitary creation fueled by individual suffering, , the truth is most of us thrive in some way in creative community, and af Klint's groundbreaking abstract work is an example of creative work that was deeply rooted in collective practice.

The group provided not just spiritual guidance, but a social and intellectual scaffolding that fostered and validated unconventional artistic methods like automatic drawing and channeling. It was a safe creative space in which to play. This communal support was likely critical for a woman artist operating outside the male-dominated academic and gallery systems, allowing her to develop a radical visual language without immediate external judgment or dismissal.

Pioneering Abstraction: A Visual Language for Higher Consciousness

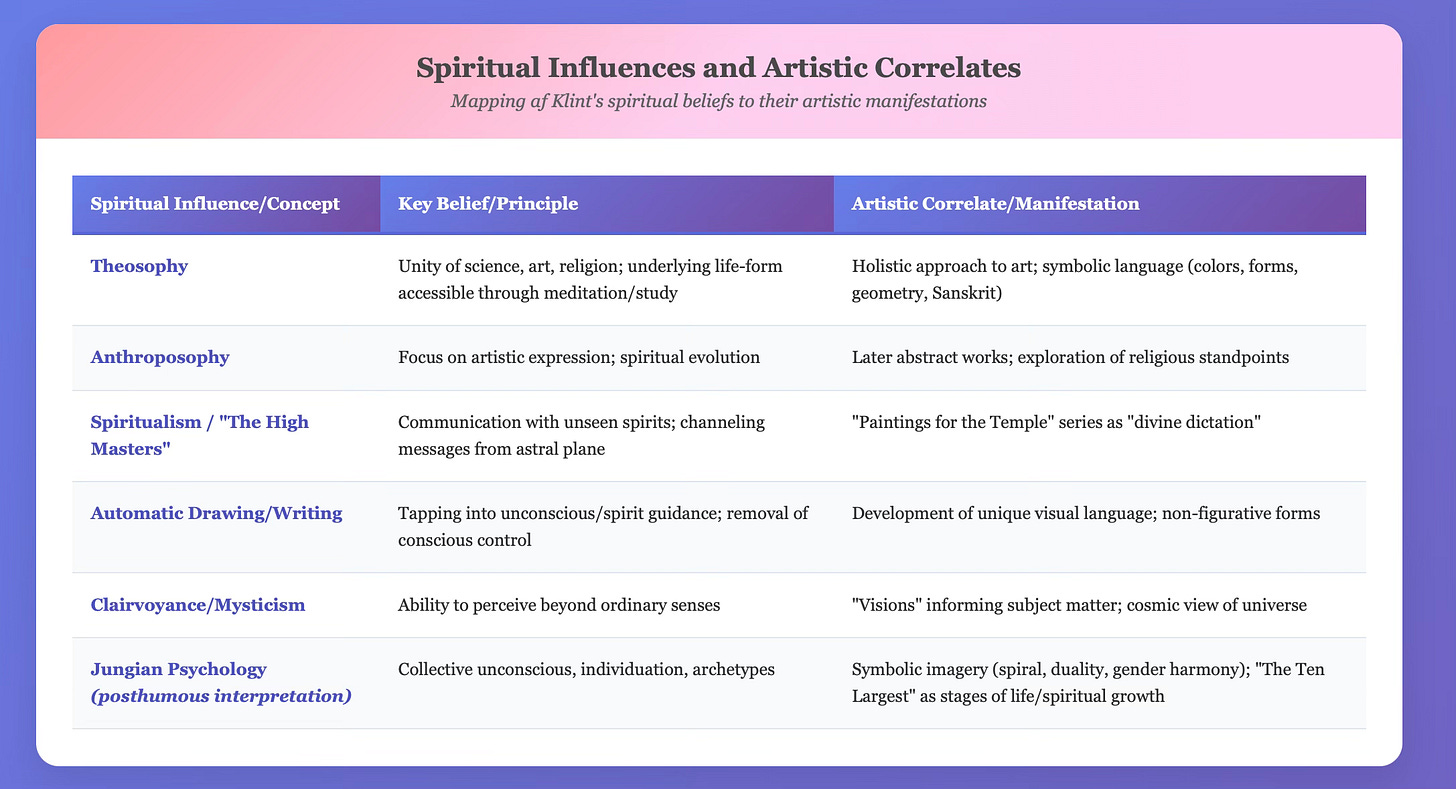

Let’s take a look at some of the ways that Klimt’s spiritual beliefs manifested in her artwork:

This systematic mapping of Klint's spiritual beliefs to their concrete manifestations in her artistic practice provides an overview of the intellectual and spiritual framework guiding her work. This is essential for understanding her unique approach to abstraction. Without comprehending these influences, her abstract forms might appear arbitrary, which they most certainly were not. By correlating specific spiritual concepts with their artistic outcomes, this table visually demonstrates the systematic and intentional nature of her abstract language, countering any perception of her work as merely "random" or "pathological" visions. It serves as a Rosetta Stone for deciphering her complex visual vocabulary, making her work more accessible to an academic audience and reinforcing the interdisciplinary focus of this report.

Hilma af Klint began painting non-figurative works as early as 1906, firmly establishing her as an early pioneer of abstract art, years before her male contemporaries, which directly challenges the established narrative of abstract art's origins, which was largely centered on the European avant-garde and emphasized the autonomy of the art object. Klint, conversely, viewed her abstractions as mediums for spiritual communication rather than ends in themselves, a fundamental difference in approach that contributed to her initial obscurity, and contributes to the power of her work.

Paintings From The Temple

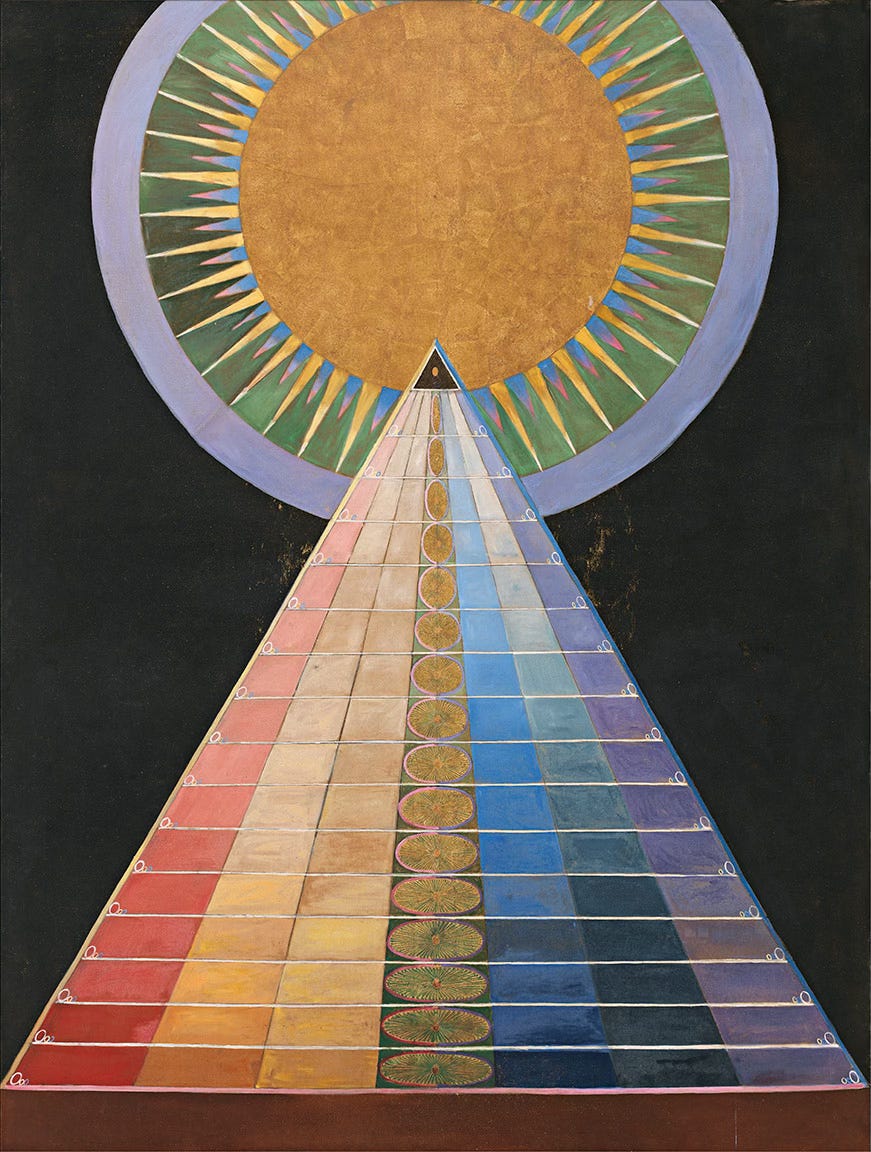

Her most significant undertaking was the monumental "Paintings for the Temple" project, created between 1906 and 1915. This series, comprising 193 powerful paintings, was conceived as a "new philosophy of life" proclaimed through art, guided by the spirit Amaliel. The works are subdivided into thematic groups exploring metaphysical concepts and the evolution of human consciousness from youth to old age. Notable examples include series titled "Primordial Chaos," "Eros," and "Evolution."

I was intrigued by this story of how this series began:

“During a séance in 1906, Hilma af Klint was asked by Amaliel, one of the High Masters, to take on a project more extensive than the automatic drawings she had been producing with The Five. The other women in the group were not willing to accept this commission and warned af Klint that the intensity of this kind of spiritual engagement could drive her into madness. Af Klint accepted anyway.”

Klint developed a complex symbolic language using colors, forms, and geometries drawn from Theosophy and other esoteric traditions to create what she intended as a "universal language of spiritual truth." Her color choices were highly metaphorical: blue represented the female spirit, yellow the male, and pink or red signified physical or spiritual love. The overlapping of blue and yellow frequently produced a soft green, symbolizing gender harmony and unity. Her paintings also feature geometric and organic forms such as spirals, which represent the soul's evolutionary journey, as well as circles, intersecting lines, waves, and particles. These elements reflect her interest in contemporary scientific discoveries like quantum mechanics and electromagnetic waves, demonstrating her unique melding of science and spiritualism. Her compositions often depicted symmetrical dualities, such as up and down, in and out, earthly and esoteric, or male and female. Furthermore, she incorporated letters and words, sometimes from the Sanskrit alphabet, alluding to sacred sounds and creative power.

A striking sub-series within "Paintings for the Temple" is "The Ten Largest," created in 1907.

These monumental canvases, each over 10 feet tall, were completed in a remarkable six-week period. Their dynamic, swirling compositions depict the stages of life from childhood to old age, vibrating with spiritual energy. The monumental scale and rapid creation of "The Ten Largest" suggest a manifestation of heightened creative flow. While af Klint attributed this to "spirit guidance," such rapid, prolific creation can be observed in states of intense creative absorption. This intensity of creative drive, whether spiritual or psychological in origin, shares characteristics of profound absorption and energy, allowing for a discussion of creative states that transcend typical diagnostic labels and inviting a broader understanding of how intense inner experiences can manifest in extraordinary artistic production. In other words, we could dismiss this as some kind of mania - and perhaps it was in ways - but that doesn’t mean we should pathologize it.

Other Hilma af Klint Works

After completing "Paintings for the Temple" in 1915, af Klint's "divine guidance" reportedly ceased. However, she continued to pursue abstract painting independently, often using watercolors and creating smaller works. In this later period, she explored different religious standpoints and the duality between physical and esoteric levels. This evolution demonstrates a transition from channeled creation to self-directed artistic exploration, showcasing her sustained commitment to abstract expression.

Contemporary Jungian thinkers and scholars have extensively analyzed af Klint's work, viewing her artistic and spiritual journey as a profound engagement with Carl Jung's concepts of individuation and the exploration of the collective unconscious. Her automatic drawings and abstract paintings are seen as anticipating Jung's concept of active imagination and his understanding of the archetypal realm. Jung posited a "transconscious disposition in every individual which is able to produce the same or very similar symbols at all times and in all places," a concept that resonates with af Klint's universal symbolic language.

Her paintings, particularly "The Ten Largest," "The Swan," and "The Dove," are interpreted as visual representations of the individuation process, which is the journey towards self-realization and the integration of conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche. These works depict stages of spiritual growth and the integration of opposites, central themes in Jungian psychology. The spiral, a recurring motif in her work, symbolizes this evolutionary journey of the soul and psychic transformation. Furthermore, af Klint's exploration of gender in her paintings, with abstract forms resembling reproductive parts unattached to bodies and the overlapping of male (yellow) and female (blue) colors to create unity, is interpreted as an exploration and integration of the anima/animus. Her work is seen as leading to "harmony beyond sexual difference" and resonates with contemporary fascination with nonbinary and transgender identities.

Synesthete?

I have long been intrigued by the condition of synesthesia, something I know that I can’t really comprehend because it’s not my experience of the world but that I love to learn about anyway, and have been lucky to meet some people who have shared their experience of it with me. Was Klint a synesthete?

Speculation exists among individuals associated with the Hilma af Klint Foundation, including family members who also possess the trait, that af Klint did indeed experience synesthesia. Her "visionary renderings" are interpreted as a "journey through her inner life as a synesthete," where "richly hued photisms"(colored shapes perceived in response to sound or other stimuli) appear kinesthetic and motile within her geometric compositions. This perspective suggests a neurological basis for her unique visual experiences, which may have profoundly influenced her distinctive artistic style.

Catalog descriptions of af Klint's work sometimes refer to her "visions" in a casual manner. However, contemporary analysis emphasizes that the definition of "pathology" is relative. Experts caution against definitively labeling her experiences as pathological, highlighting that her "visions" or "hallucinations" (if they occurred in a clinical sense) should be understood within the context of her deep spiritual engagement and the evolving understanding of mental health. Curator Massimiliano Gioni says:

“Af Klint had visions or hallucinations—I don’t know if they were pathological or not, but we have enough history under our belts to understand that the definition of pathology is relative, and historical, and cultural.”

For af Klint, her art was primarily a "medium for spiritual communication rather than an end in itself." This framing of "visions" as a unique mode of perception and spiritual engagement, rather than pathology, is critical.

Synesthesia may be a plausible neurological basis for understanding her unique visual experiences. We don’t know for sure.

Beyond the potential for synesthesia, a striking parallel can be drawn between af Klint's artistic process and experiences often reported during psychedelic journeys. The connection between af Klint's art and the psychedelic experience extends beyond mere visual similarities to touch upon the profound psychological states they evoke. Psychedelics frequently induce a profound realization of interconnectedness and universal truths, blurring the lines between the physical and metaphysical. Similarly, af Klint's art, with its intricate spirals, mandalas, and luminous colors, acts as a portal, inviting viewers into realms where reality blurs and deeper consciousness is stirred, often mirroring the experiences reported during altered states. This parallel suggests that both art and certain altered states of consciousness can serve as pathways to exploring the "inner landscape" of the mind, potentially offering unique modes of perception and engagement that challenge conventional understandings of mental states and reality itself. This can be viewed not as a pathological deviation, but as an exploration of the vast capabilities of the human psyche to perceive and express profound truths beyond ordinary sensory experience.

Legacy: Reception, Gender, and Art Historical Revisions

Hilma af Klint's decision to keep her work hidden for at least 20 years after her death stemmed from her conviction that the world was "not yet ready" for her profound spiritual messages and pioneering abstract forms. She expressed a hope that with the passage of time, humanity would develop the capacity to receive the inherent message in her spiritual paintings. This directive underscores her long-term vision and her astute understanding of the limitations of her contemporary art world.

This intentional obscurity represents a visionary critique of the contemporary art world. Her decision to withhold her work for decades was not merely a personal eccentric quirk; it was a strategic act of profound foresight. She recognized that the "male-dominated art world of the early 20th century" and its "rigid acceptance of new forms" were not equipped to understand or appreciate art born from spiritual mediumship and a desire to express unseen realities. Her belief that the world needed to "attain a certain level of spiritual and consciousness evolution" before her work could be fully appreciated transforms her "obscurity" into an active, visionary choice, a deliberate withholding of her profound message until a more receptive era. This implies a sophisticated understanding on her part of the societal and art historical biases of her time, turning her "silence" into a powerful, long-term statement about the future of art and consciousness.

Her prolonged absence from art historical narratives meant that male artists like Kandinsky were widely credited with inventing abstract art. Klint's emergence fundamentally challenges this established chronology, positioning a woman at the genesis of abstraction. The Ten Largest not only outsized Picasso's Les Demoiselles d’Avignon but also "departed more radically from the conventions of European art." This discovery necessitates a crucial re-evaluation of art history to include the vital contributions of women artists and to move beyond narratives focused on the "existential crisis of a heroic individual."

The art world of the early 20th century, largely secular and focused on formal innovation, often trivialized or dismissed spiritualist practices. Klint's abstractions, deeply infused with esoteric symbolism and conceived as direct spiritual communications, did not align with the prevailing understanding of abstract art's genesis, which emphasized the breaking of representational boundaries and the autonomy of the art object. Her unique visual vocabulary, coded with personal revelations, was not readily decipherable or appreciated by a mainstream accustomed to conventional lexicons.

The 21st century has witnessed a dramatic shift in her reception, with the Guggenheim's 2018-2019 exhibition becoming its most popular in 60 years. Her work resonates profoundly with contemporary audiences, particularly those interested in nonbinary and transgender identities, as she explored gender binaries as "puzzles to be solved, not permanent features of reality." Her attunement to intangible forces from the natural world and her melding of science and spiritualism connect with current interests in animism, spiritual ecology, and environmental concerns. Her message of interconnectedness and the unity of all life is seen as highly relevant in an age of increasing spiritual and ecological crisis.

Hilma af Klint stands as a pivotal figure who profoundly impacted the trajectory of modern art, not through conventional means, but by bridging seemingly disparate realms: the visible and invisible, the scientific and the spiritual, the personal and the universal. Her art, born from a deep spiritual quest and channeled through unique psychological experiences like synesthesia and a profound engagement with the collective unconscious, offers a visual language for higher consciousness. She demonstrated that art could be a medium for spiritual truth, a map of the psyche, and a reflection of cosmic principles, challenging the boundaries of artistic expression and its purpose.

Klint's belated recognition forces a crucial revision of art history, acknowledging the vital contributions of women artists and the profound influence of spiritualism on abstract art's genesis. Her legacy invites a reconsideration of the origins of creativity, the nature of perception, and the interconnectedness of all life, affirming the transformative potential of art to help humanity confront mysteries within and without. Her work remains a potent reminder of our shared humanity and the enduring power of art to connect us to deeper truths, should we be ready to receive them.

If you read this far, you probably liked the work. The work takes work. Support it if you can.

You Might Also Like to Read:

which includes:

I found your account through someone's sharing of this article in my feed.

My interest in abstract art in general and af Klint in particular preceded my experiences with consciousness-altering plant medicines. I appreciate your work on this excellent piece and am sharing it here on Substack and elsewhere. Thank you!

Great article, thank you!