Art History Meets Psychology: Sam Gilliam, Bipolar Depression and the Impact of Medication on Creativity

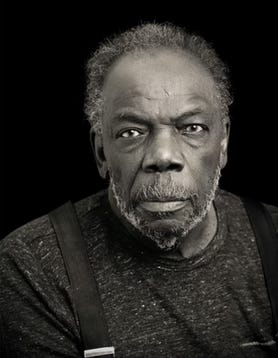

Abstract art "challenges you to understand something that is different, that a person can be just as good in difference"

I recently read the wonderful profile of Sam Gilliam’s work that

shared. Doing so reminded me that I had drafted a chapter of The Artist’s Mind about Gilliam’s work, and then that chapter got cut in the editing process. Gilliam was still alive when I wrote this in 2020 - hence the present tense - of the kidney disease caused discussed in the article; the disease was at least partially caused by his many years taking Lithium for his mood disorder.“I’d always been afraid of art. I was afraid in college. But that fear is a goal, in a way: It makes you hesitate, and then you delay your start, and then you have a breakthrough.” - Sam Gilliam

Sam Gilliam has been a painter for six decades. Success with his career has seen ebbs and flows; he gained great recognition in the 1960’s and 1970’s and then the world stopped paying so much attention to his work for a while. But then in the twenty-first century, recognition once again swelled. In his eighties, Gilliam is still painting prolifically and the world is excited to see his work. Mostly, these fluctuations in popularity can be chalked up to the whims of the art world. However, the artist’s struggles with bipolar depression, about which he has been very open, did sometimes impact his ability to create his work.

Throughout this book, the big question we’ve been exploring can be summed up as: what is the relationship between an artist’s mental health condition and their art? We will explore this subject with Gilliam, too, but he presents us with a unique opportunity to look even more closely at another question: how does the treatment for a mental health condition impact the artist’s work? Of course, we’ve explored this to greater or lesser degree with other artists, particularly in regards to how their time spent in an institution setting helped or hindered their artistic process. For example, we saw how Alice Neel suffered in the asylum that would not allow her to create art, but thrived in the hospital that did. And we saw that Jacob Lawrence’s piece Sedation directly addressed this question, making it a piece of conversation over the years. With Gilliam, we have the opportunity to look even more closely at the link between treatment and creativity, particularly as it applies to people in modern society, due to the direct impact that the medications he has taken for bipolar depression have had on his art.

There was a point in Gilliam’s career, at the beginning of the 21st century, when he found himself unable to create despite his decades of history as a professional painter. Really, he struggled to function much at all. The assumption for a long time, by Gilliam, his family, and his doctors, was that the depressive aspect of his lifelong condition was causing the problem. One of his daughters described him as “catatonic on the couch.” He barely left the house for three years and didn’t know if he would ever paint again. Depression was certainly part of the cause. But the medications were also a significant part of the problem. His family could clearly see that the drugs that were purportedly helping him manage his condition were also responsible for his lethargic state of being. It’s not easy to decide whether or not to take medication, and to what extent, when on the one hand it’s helping you stay “sane” but on the other hand making you numb to life. Gilliam wanted to create art again. His family rallied behind him, helped him to get new doctors, and once on the right medications, everything quickly changed.

To better understand this, let’s circle back to the earlier stages of his career. Sam Gilliam’s work defies definition, due in part to the authenticity of his own original vision, and in part to the fact that he’s consistently changed styles over the course of his 60+ year career. A 2005 retrospective book by Jonathan P. Binstock for the Corcoran Gallery of Art emphasizes that although Gilliam is most often associated with the Washington Color School, “What has distinguished his aesthetic over the years is not its historical link to the Color School but how he upset the tradition of modernist art that Color School painting represents.” In a 2020 interview Gilliam said,

“I like this experience of coming up with something different. That’s what I’m here for...That’s what art is supposed to do; it’s supposed to change.”

Gilliam started drawing in dirt as a child and someone told his mother that he had talent and she should always make sure he had paper. She did just that and he began to draw horses prolifically. He credits his seamstress mother for this early support of his creativity. Inspired by comic books, Gilliam initially wanted to be a cartoonist. He would go on to draw and paint figuratively for a short period of time, but he began to stray from figurative work early in his career, instead favoring abstraction.

The artist gained attention in the late 1960s for a unique technique of painting on canvases without frames, then stretching them in unique folded positions for display. The technique, born accidentally when a canvas he was hanging fell to the floor, and also inspired by weighted clothes hanging on a clothesline, came to be known as “Draping.” Although the design was born accidentally, perhaps his early experiences watching his seamstress mother gave him the eye to recognize the beauty inherent in this casual falling of the fabric. Into the early seventies, this “Draping” work was displayed in several important shows including the 1972 Venice Biennale, where he was the first African-American artist to ever show. One of these draped pieces, Carousel Form II, made the cover of a 1970 issue of Art in America. Around the same time, Gilliam received a prestigious Guggenheim Foundation Award. Despite all this recognition, interest in his work eventually waned. He wasn’t content to stick with one style and his new experiments weren’t as welcomed by the art world, which often relies on artists to maintain a signature look. Further, many theorize that his unwillingness to create in ways that would be stereotypical of a “Black artist” held him back commercially. For example, he didn’t participate in marches or political protests. And often, he intentionally chose to leave the subject of race out of his art. He continued to create and to do modestly well as a working artist, but he didn’t steadily sustain the same acclaim and success.

Like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jacob Lawrence, Gilliam gained recognition as a Black artist at a time few others did, and battled with appreciating the recognition and at the same time not wanting to be tokenized. Occasionally, he did let race and political issues into his decisions about art. In 1971, for example, he was slated to participate in a Whitney Museum of American Art show dedicated to Black artists but eventually decided, along with six other artists, not to participate because of the racism and tokenization they found inherent in the experience. They didn’t want to be selected only because of being Black, and they didn’t want “Black” to be their primary identity as artists. They didn’t want white people being able to say, “I went to this show, so I understand the Black experience.” Gilliam has been clear in interviews that his racial identity is important to him as a man, but isn’t what he wants attention for as an artist. Whereas Basquiat regularly included Black bodies in his work, Gilliam has intentionally opted not to, a decision which New York artist Rashid Johnson calls “radical.” In a 1973 article, Gilliam elaborated:

“I think there has to be a Black art because there is a white art. … Being Black is a very important point of tension and self-discovery. To have a sense of self-acceptance we Blacks have to throw off this dichotomy that has been forced on us by the white experience. For some there is a need to do this frontally and objectively.”

So, he was not unaware, of course, that being a Black artist means creating Black art, but he never wanted that to be the point of his work. That said, Gilliam doesn’t necessarily think his art is apolitical either. In a 2020 interview, he shared that he believes abstract art has the power to effect change because “...it messes with you, it convinces you that what you think isn’t all, it challenges you to understand something that is different, that a person can be just as good in difference.” Perhaps his experience of living with bipolar depression, especially when it was even more highly stigmatized than it is today, helped him to develop this point of view. In the 2017 film All These Flowers, which follows the stories and treatment choices of several people diagnosed with bipolar depression, one man poignantly describes his experience as such:

“Imagine that you could feel that 2+3=7. Imagine that though you looked over and over again at the equation, it didn’t seem right that 2+3=5. It seems like you have a special insight that it equals seven and somehow you know deep down inside that it really equals seven and that this is all a lie, that this whole 2+3=5 thing is a lie, you know. And so deep down you know that it really equals seven but you can’t prove that to anyone else. They’re all in on it, accepting that it’s 5, and they can prove it “objectively”, but you feel, you know, the truth, and that it’s seven. That’s what you’re battling with.”

This person in the documentary describes how he, personally, has chosen not to take medication because he doesn’t like the way that it makes him feel. But that as a result of that he has had to consistently retrain his brain to recognize that even though he totally, fully, one hundred percent thinks that something is “real” or “true” doesn’t mean that it’s so. It might just be his bipolar brain telling him something that isn’t correct. This sounds so similar to what Gilliam said about how art can transform the way that we think and show us that things may be different than we believe them to be.

There are a lot of stereotypes about people who live with bipolar disorder, stereotypes that persist in part because there is some truth in the patterns. Research has shown, for example, that there is likely some link between hypomania / mania and creative impulse but this doesn’t always mean that someone with bipolar mania is going to be able to be creative. So the myth persists because there is a link, but it is also an incomplete version of the full story. And of course each individual is different, and Sam Gilliam does a great job of defying many of those stereotypes. For example, one stereotype is that it’s hard to live with someone who is bipolar due to their changing moods, a notorious unwillingness to stay on medication, and the reckless behavior that can occur during manic phases. While we can't know for certain that Gilliam was never hard to live with, we can say through and through that he is a loving and supportive husband and father. Born into a large family, he graduated from the University of Louisville with a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts, then promptly moved with his wife, Dorothy, to the Washington DC area so that she could pursue her dream to become the first African American woman hired as a reporter for The Washington Post.

In her 2019 autobiography Dorothy does acknowledge that their marriage has endured some challenges, but she generously attributes as much of the trouble to her own mental health challenges and the general difficulties of getting married young as to anything specific to her husband’s mood disorder. She does note that as soon as they got married in 1962, she noticed her husband seemed troubled and couldn’t fathom why, going on to say, “I never found out what had upset him, but it foreshadowed a pattern.” The following year, around the holidays, Sam became deeply depressed and had to be hospitalized for a two-week period. Although doctors and psychiatrists already recognized his highs and lows as bipolar depression, at the time there simply were not any effective medications available to help him.

Although Sam and Dorothy divorced in 1982 after two decades of marriage, he stayed in Washington DC because it was important to him to remain close to his three daughters. Family has always been very meaningful to him. He even scheduled his studio time around their activities in order to spend as much time with them as possible. After his divorce, he began a new relationship with partner Annie Gilwak. That turned into a decades-long relationship, showing again that family was important to him. His family would play a critical role in helping him to heal and create again later in life. This support system is critical for people living with any mental health condition and likely has been a big reason why he has been able to manage through the decades despite the sometimes-debilitating nature of his condition. If there’s a stereotype that people with bipolar depression aren’t “good family people,” Gilliam is a great example of how untrue that can be.

Gilliam also defies the stereotype of the person with bipolar depression who won’t take their medication. People with this condition are often called “non-compliant” because they stop taking their medication. There’s a reason they stop. Although medication levels them out, many people also report feeling sluggish or zombie-like on their meds, and some might miss the intense energy of manic episodes. What also often happens is that patients will be doing quite well on their medications and feel like they don’t need them anymore. But none of this was true for Sam Gilliam who began taking Lithium in 1976 when it was new to the market. He continued to take it faithfully for decades, to the point where the drug eventually destroyed his kidneys. He only stopped when he and his family realized that the drug was limiting his quality of life, including (but not limited to) his ability to create. (He didn’t stop meds entirely; he switched to new medications now that there are many more options for people living with bipolar depression.)

Now in his eighties, Gilliam is magnificently prolific in his studio and seeing some of the most significant appreciation of his work to date. He has had solo shows and retrospectives. Major museums, including MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have acquired his work. In 2016, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture unveiled a nearly 30 foot long artwork, “that is one of the highest profile commissions of his career,” and of which the artist is particularly proud. In 2018, he had his first solo show at a European museum, at Switzerland’s Kunstmuseum Basel. Some of his works are now selling for prices that exceed one million dollars.

Throughout the decades, Gilliam’s world had shrunk. For example, when he was in the midst of his depression, he had stated that he wasn’t going to travel again. But that’s all changed since he’s been on new medication. His partner convinced him to travel, opening his eyes to new possibilities including giving talks about his work. This is despite the fact that as of 2018 he was going to dialysis three days per week, four hours per day, to treat his failed kidneys. In a 2020 interview he expressed that he wants to “leave something of value, to create some hope” and that he believes he is good at that. It is so hard for any artist in society to maintain faith, optimism, and belief in their work over the decades, especially with ups and downs in critical reception. And it’s so hard for people living with mental health issues to sustain that belief in themselves over time especially when living with a very stigmatized condition. Gilliam has managed both.

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing.

Art For Thought

Let’s take a closer look at one of Gilliams “Draped” paintings: Double Merge (1968). This is from the time when the artist was starting to gain recognition for this unique approach to art. However, it was before he made the cover of Art in America or became the first African American artist to represent the United States at the Venice Bienale. So, it was at a really pivotal time in his career, when he was truly in the thick of developing an innovative new approach to art.

It was also an important time in his personal life. He had only been married for a few years at this point. His wife had already noticed his depressive periods, and in fact, he had already spent some time in the hospital. His doctors already recognized him as experiencing manic depression (what we now call bipolar.) But there weren’t any medications for him, yet. Lithium wouldn’t come on the market for another few years. So he was creating this amazing new work of art while also coping unmedicated with the symptoms of his bipolar condition.

Double Merge is a colossal work of art. Artnet News calls it an “ambitious, gallery-swallowing” piece. Hyperallergic says, “Walking through the draped artwork — which hangs from the ceiling like a marionette — feels like swimming, or floating, through swathes of melting pastel shades.” And ArtForum says that it is “like a pair of enormous paint-soaked wings.” In fact, the work consists of two separate canvases, both titled Carousel II, that he then merged together into one complete work. He’s removed the stretchers characteristic to painting on canvas, and the fabric hangs “evoking kingly robes or theater curtains.” It’s impossible here not to draw connections to “out of the box” thinking. Mental health challenges literally exist inside of the brain - the chemicals, the neurotransmitters, they’re reacting differently inside this brain than in the brain of the “average” person. And so perhaps the individual living inside this brain sees things differently, and perhaps if this person is an artist, it allows them to express that unique vision to others. Double Merge has so many varied colors, reminiscent of tie-dye and starbursts, and it looks different from evety single angle.

This piece is also a great example of how Gilliam diverged from the art, and the expectations of artists, at this time. Artnet News explains, “the mid-‘60s transition from the Civil Rights to the Black Power period was making very clear demands on black artists like Gilliam for political content, and for disaffiliation from white power structures, of which abstract painting was sometimes thought to be one.” Gilliam, and other Black painters, felt a lot of pressure not to work in abstract art, and yet he chose to pursue this work anyway. Of course, he wasn’t entirely alone. Hyperallergic points out, “His career launched during a time when African American artists were often infatuated with and obliged to work with figuration, but his abstractions were in good company among the likes of Alma Thomas, Howardena Pindell, Frank Bowling, and Ed Clark.” But the point here is that people looked at, and judged, his work through the lens of his being a Black artist, and so taking the risk of not only sticking with abstraction but expanding upon it with works like Double Merge couldn’t have been easy. And that’s what makes it so striking.

In 2019, the Dia:Beacon museum opened a permanent exhibition of his work, which includes Double Merge, which is hung from the ceiling. Each time that this piece, or any other of Gilliam’s Draped paintings hangs anew in an exhibition, it’s never hung the same way as in the past. This is simply in the nature of the work itself; the way that the sculptural fabric folds over on itself differs each time. And perhaps this brings us back to that idea that art can always teach us to see something new. Each of the two pieces in Double Merge is unique, tough they go together. “They are marked as having their own logic.” Juxtaposing them as a single piece allows you see that they are individual, different, but also connected. Imagine that you live with bipolar depression: that you experience neutral times like anyone else, but then you see the same things (relationships, nature, the world itself) through periods of hopeless darkness and again through periods of excited manic intensity and joy. Each time the thing is the same, each time you see it differently. In the same way that Gilliam’s draping took painting from 2D to 3D, maybe the way that the work shows differently each time takes it to a place of metaphorically expressing the changing views of a brain over time. At the age of 83, Gilliam told an interviewer, “I am just getting started.”

RESOURCES

Edgers, Geoff. “The Not-so-Simple Comeback Story of Pioneering Artist Sam Gilliam.” The Washington Post, 2016.

Lewis, Jim. “81-Year-Old Artist Sam Gilliam Is Having a Moment: It's About Time,” 2014.

Loos, Ted. “At 84, Sam Gilliam Fires Up His Competitive Spirit.” The New York Times, 2018, International edition.

Lund, Christian. Sam Gilliam Interview: Artists Are Supposed to Change. Video. Louisiana Channel. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2020.

Messman, Lauren. “At Last, Sam Gilliam’s Star Ascends in New York.” The New York Times, 2019, sec. C.

Miller, Donald. “Hanging Loose: An Interview with Sam Gilliam.” ARTNews, January 1973.

Solomon, Deborah. “Sam Gilliam Unfurls an Exuberant Rainbow at Dia:Beacon.” The New York Times, 2019.

Valentine, Victoria L. “Almost Famous: The Ebb and Flow of Sam Gilliam's Formidable Practice.” Culture Type, 2016.

This is an amazing article on Sam Gilliam, a man I had not heard of before. I personally know how medications can change our personalities. I broke my neck early on in the year 2000. I was put on Oxycontin, Sarafem (a Prozac derivitive), and Ambien for good measure. I became a person who never cried, who had QVC on a loop, and bought shiny gold and porcelain dolls, things I had never been interested in before. I raged and threw myself on the floor and yelled "F#*& You!!! to my loving and ever patient husband.Sensing the dangerousness of myself, I put myself to bed. Eventually, my doctor recognized my dependence and forced me to "cold turkey" all three drugs at once. I lay in the bathtub begging God to take my life (but not during Christmas...I didn't want my children to associate Christmas with my death). At the end of January I came back to myself. I boxed up the dolls and picked up my paintbrush. Thanks for this article, Kathryn. Fascinating.