The Schubert Treatment: A Story of Music and Healing

Sometimes we need to cry and music helps us get there. Sometimes we need to dance and music helps us get there.

“What pushed the musician I was toward a care profession wasn't a moral imperative but something natural, instinctive; something innate.

Music, in the curved form of the cello, became my life, and stood like a bulwark against absurdity, disease, and death, to try to reach the thing that lies beneath, the thing that resists. Subterranean. Bedside music. Trust: a refreshing wind.”

- Claire Oppert

In my exploration of the complex relationship between art and health, one of the things I find fascinating to investigate is how the consumption of art, as opposed to the making of art, can be healing (or triggering/traumatic, for that matter). Usually, when people discuss the benefits of creativity, they mean in the making of it, but there’s something special about reading, watching, listening to the creativity of others that can also be healing.

Music does this in ways I can only begin to understand. I don’t have a strong relationship with music … meaning that I don’t really play an instrument, I don’t often go to concerts. I love music like almost all humans love music but I don’t get immersed in the nuances of it in the way that so many of my more musically-inclined friends do. And yet, even I know that pausing what I’m doing to sing along with a song can completely change my mood and attitude.

Here and there I’ve learned about how music reaches a unique part of the brain and so often helps with memories for people with age-related memory loss. I’ve learned how playing music in utero might have an impact. I’ve attended meditation sessions combining viewing an art piece with listening to music. I’ve seen music heal, in at least small ways.

Most recently, I enjoyed reading Claire Oppert’s memoir The Schubert Treatment: A Story of Music and Healing. Oppert was a classically-trained cellist who brought her music into hospitals and residential centers to share it with non-verbal individuals on the spectrum, elderly patients experiencing dementia, and various other populations that some healers tend to think of as difficult to reach. Her music reached them. She started out without a strong psychological/neurological background and learned from the people themselves, later going to school to supplement her anecdotal and observed experiences with science. In the book, she shares stories of different people who were impacted differently by her music alongside her own experiences as the musician.

For example, Oppert describes coming in to play music with elderly women, one who has schizophrenia, another Lew body dementia, another mixed dementia, and each responds differently, but each gets something out of it. She quotes them as saying:

"Music speaks to something vital, something essential within us, the most beautiful part of us. It transforms the person who is singing. It's a miracle."

"Were not afraid of making mistakes here. We feel important now. We feel good. We feel at home."

"Yes, we feel like we belong."

Making music together returns them to parts of themselves and also connects them to others. In this case, the women are playing music as well, not just listening to it. Sometimes the patients are at first listening and then spontaneously begin to sing or tap along. Other times, they are “just” listening. And all have healing aspects.

An example of how simply listening to the music heals that Oppert shares:

“Her eyes become animated, She doesn't interrupt my playing, but at the end of the piece, she say, "Wait' Her voice is nasal. "There's something coming back to me after all." A few scattered fragments emerge from her slumbering mind.

The cello's voice calls up her memories, one by one. They hiccup forth and rise to the surface like rainbow soap bubbles bursting.

We may think things have been swallowed up or erased, but sometimes music can retrieve memories from hidden cor-ners. Light flickers deep within the cello's chords. The strange feeling of being outside of yourself fades. Madame Vaillant can't exactly retrace the trajectory of her life, but we manage to connect the few pieces she lets through, enough to build a narrative.”

Oppert wraps up this section by saying:

“And although most of them will leave the room and immediately forget the cello, the bells and the drums, the strolls in the woods, the furtive caress of the wind, the swell of emotions and the kind words they've exchanged, it doesn't matter, because the attendants who are helping them back to their rooms are singing. An incomparable flash of light brightened the patients faces for a few infinite minutes, and a glimpse of their flickering souls showed through, whole and intact.”

Some of my other favorite passages from this book, which all give me so much to keep thinking about, include:

“Music seems to make up for the absence of language. In the very depths of her being, she has some form of musical prescience, the evidence of which can be seen in her frantic wincing as she listens to every inflection in the melody-she's tense when the cello sings the first development, there's the ecstasy of the recapitulation, and she relaxes with the ebb back to the original key. She listens to the cello in a state of paroxysmal joy. She tosses her head and howls with pleasure.”

“He is a cultivated man. He wields language with dexterity, and his comments are invariably pertinent. He talks about his taste for music, which goes back to childhood, and about his thirty-year subscription to the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées.

He recounts juicy anecdotes about the famous artists he met on his many trips, Our encounters, to Verdi and Puccini arias, are lighthearted and even flirtatious. His company is delightful.

But two weeks later, I find a very sick man whose condition has deteriorated considerably. I play for him again. Lying on his bed, his face drawn, he watches the cello. When I finish the sarabande from Bach's Fifth Suite, Monsieur Fridman doesn't say a word. His lips quiver slightly. There's no more banter. He gives me a wan smile and, as I'm about to leave, he rolls up his sleeve without a word and shows me his Auschwitz number.

I come back to the bed. He strokes the tattoo on his arm, and says, without looking at me, "In the face of the unspeakable and the unbearable, music ties us to the meaning of life.

Thank you. It is a balm upon my heart."

MADAME BLOCH absolutely doesn't want any music. "I'm all alone, and if you play for me, I'm too afraid that —that it will all come back." She's been admitted to the unit for a chronic pain assessment. She is another Holocaust survivor, the only member of her family. She likes music, but no, sorry, she defenitely does not want to hear the cello.

But a little later, as I'm leaving the room next to hers, I catch her with her ear to the door: when I push it open, the door smacks her in the head, quite hard. She shuffles away with her head down, caught off guard. The nurses tell me that she's been following me around like this since the morning, hiding behind every door, enjoying the cello as she chooses, and free to move away whenever the emotion becomes too intense. The music rouses some fundamental impulse in her, and she can't control it, so she's come up with a clever way to parcel out doses she can handle.

“He turns his ravaged face to me: "Do you understand? Actually, I think it's my suffering that wants to come out. You're offering me a way to stop feeling tied up. It's a way out." I play for him for a long time. "It gives some meaning to desiccated, dehumanized things," he says. Music runs through him like a current.”

This last one! What a powerful idea that music allows us an acceptable means of letting out our worst suffering. I am reminded of when I was going through a breakup in my early twenties and a friend suggested, “play a bunch of Patsy Cline songs and cry, that’s what my mom does.” And although it wasn’t the right suggestion for me, I’ve never forgotten the general message of it. Sometimes we need to cry and music helps us get there. Sometimes we need to dance and music helps us get there.

And finally …

The whole adventure raises so many questions. What is the link between the vibrations of the instrument and the deep vibrations of the human patients; what kind of resonance is that? Does music create emotions, or does it reveal them? Is it possible to measure the level of apprehension of patients in palliative care? Can emotion be measured and feelings structured in an arithmetic grid without the whole exercise becoming absurd?

But before I wrap up this essay, I want to note something else in the book - a description of the perfectionism of the classical cellist. If you’ve read my work for a while, you know that I believe deeply:

We are not all "tortured geniuses" and art isn't always therapy - both things can be true but most of where art meets psychology is in the rich magical middle of those two experiences. That middle is what Create Me Free is all about.

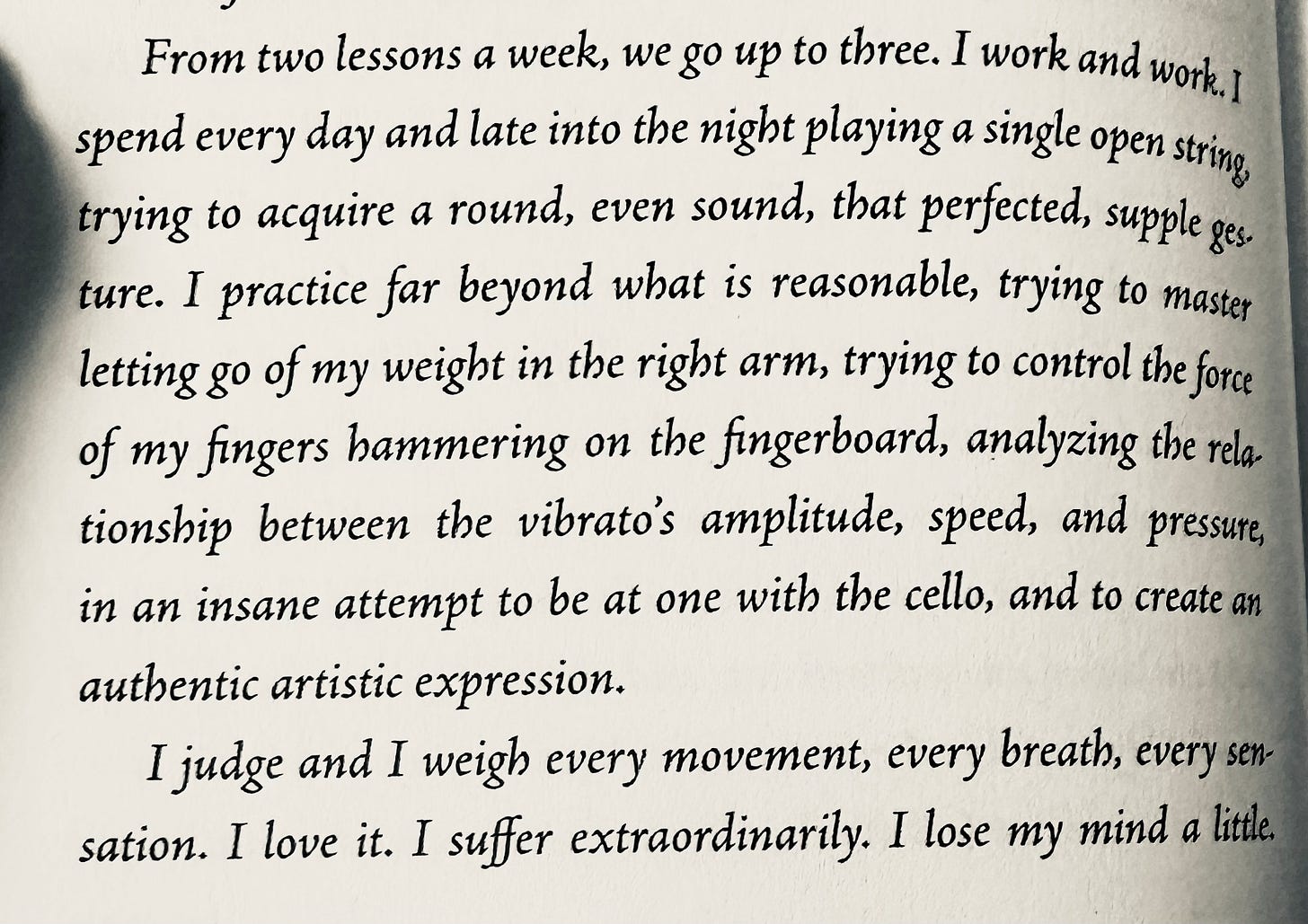

And it is with that in mind that I read this selection from Oppert’s memories of her own experience of learning to play the cello:

I lose my mind a little.

As a reader, I’m still gnawing on that one …

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

You Might Also Like to Read:

My writing on music and mental health including:

And writing about other books I have read:

Essay Collection: Books Where Art Meets Psychology

Here you will find links to the essays here on Create Me Free that are about books, mostly books I’m reading, occasionally broader thoughts about books, as they relate to the intersection of art + psychology.

Powerful words and stories. Glad to learn about Claire's book and her work. Thanks Kathryn for sharing it with us!

love this!