The Emotional Bypass: Using Difficult Feelings as Creative Fuel, Not Obstacles

When we ignore our body's signals and push through difficult emotions, we're missing valuable "creative intelligence". Fatigue might be asking for restoration , restlessness seeking movement ...

In the relentless pursuit of productivity, it's easy to fall into a subtle yet destructive trap: the emotional bypass. This is the tendency to push through difficult feelings rather than processing them, often in the service of maintaining creative output. We tell ourselves we'll deal with the discomfort later, believing that emotions are obstacles to our creative flow. However, research consistently shows that emotional suppression actually blocks access to the full range of human experience that feeds our art. What if, instead of bypassing our feelings, we learned to use them as potent creative fuel?

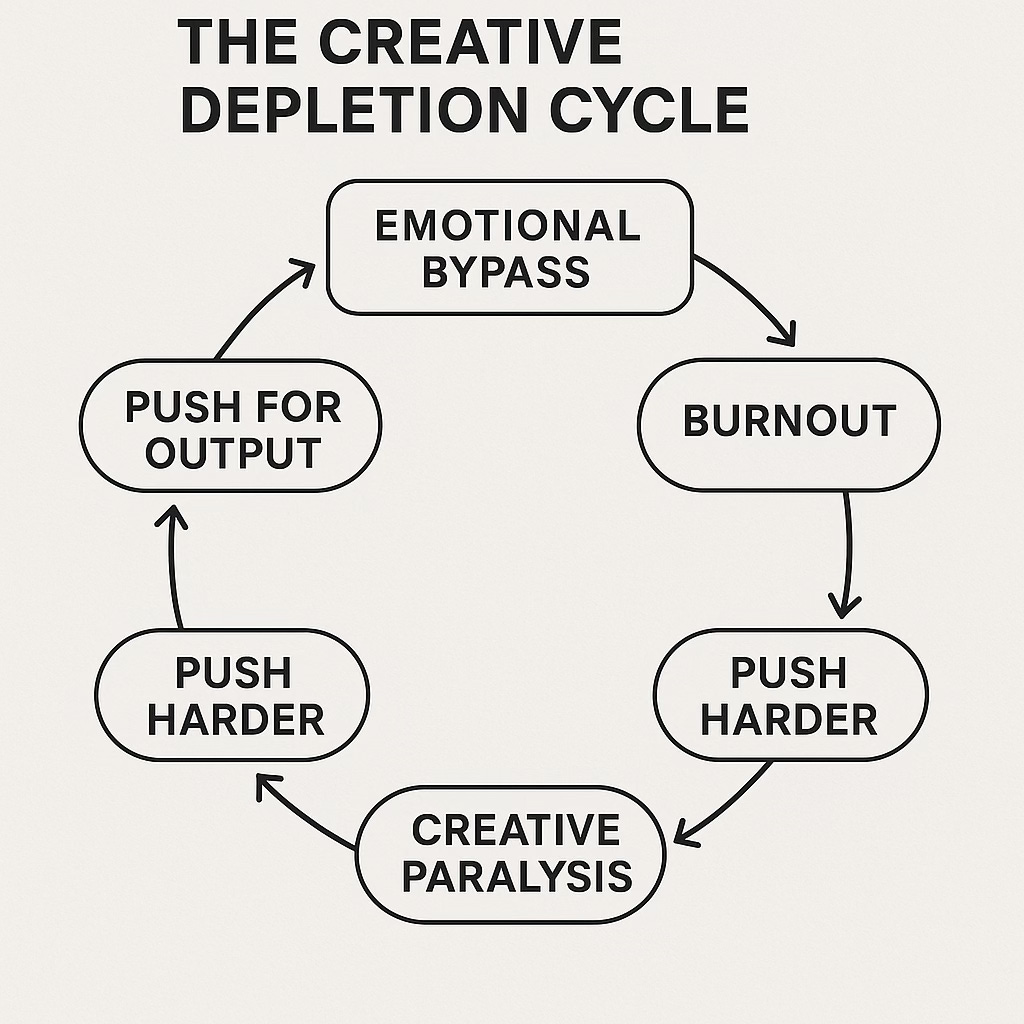

The Creative Depletion Cycle: A Foundation of Bypassed Emotions

The emotional bypass is a core component of what might be called "the creative depletion cycle". This destructive pattern begins with an insistent "push" for output , leading inevitably to "burnout". Burnout often precipitates "shame”, which is a profound emotional and self-perception barrier that tells us we are “not enough”, or that our difficulty is somehow a personal defect. In a desperate attempt to overcome this shame, we "push harder", plunging ourselves into "deeper burnout" and ultimately, "creative paralysis". This cycle highlights how our internal emotional landscape, if ignored, can sabotage the very creativity we seek to nurture.

The Psychology of Emotional Suppression and Its Creative Cost

From a psychological perspective, emotional suppression is a coping mechanism where we consciously or unconsciously inhibit the expression of our feelings. While it might offer temporary relief from discomfort, it comes at a significant cost to our wellbeing and, crucially, to our creative capacity. When we push through difficult feelings, we deplete our energy and actively work against our natural rhythms.

Neuroscience supports this. Stress hormones literally inhibit the brain regions responsible for creative thinking. Chronic exhaustion reduces our ability to make novel connections, which is the very foundation of creativity. Sleep deprivation impairs the default mode network that generates creative insights. By bypassing our emotions, we're not just harming our wellbeing; we're sabotaging the very creativity we're trying to nurture. Our work becomes less authentic because we're not accessing our full emotional range.

The idea of "pushing through" resonates deeply with the tenets of ableism and productivity expectations, which promote the myth of the "always-on creator". This societal pressure often ignores the inherent fluctuations of human energy and the necessity of rest. This external pressure can foster anxiety about how work will be received, lead to comparison with others, and even result in a "quiet fear of 'selling out' your artistic soul".

Feminist critiques of productivity further highlight how these expectations disproportionately impact marginalized groups, often demanding continuous output regardless of personal well-being or care responsibilities. To bypass emotions in this context is to internalize these oppressive norms, sacrificing inner truth for external validation or perceived success.

This aligns, also, with self-determination theory, particularly the concept of introjected regulation where external pressures (like societal productivity expectations) are internalized and drive behavior, often leading to feelings of guilt or shame when not met. The internal dialogue might become, "I must create every day, no matter how I feel", a clear sign of this introjected pressure.

Emotions as Creative Intelligence: The Body's Wisdom

Imagine your emotions not as roadblocks, but as raw, unprocessed creative material. What if anger held a vibrant color palette you hadn't yet explored? What if sadness informed the textures and forms in your sculpture? What if anxiety was a story trying to be told through your words?

This reframing aligns with the concept of emotional integration, where feelings are seen as creative material rather than obstacles to overcome. It recognizes that our physical and mental states directly impact our creative capacity. When we ignore our body's signals and push through difficult emotions, we're missing valuable "creative intelligence". Fatigue might be asking for restoration , restlessness seeking movement, and overwhelm requesting simplification.

This perspective is championed by somatic psychology, which emphasizes the body's wisdom and its role in processing emotions and trauma. The body is not lying; if a space or a process makes you feel constricted, dissociated, or fatigued, your health is being impacted. This "sensation as disruption" is valuable data, offering insights into what your nervous system needs, rather than something to be pushed through. This aligns with concepts from neuroception (Porges), where the nervous system's unconscious assessment of safety or threat influences our physiological and emotional states, directly impacting our ability to create.

Indeed, the field of disability studies again offers profound insights here. It challenges the notion that physical or mental differences are "deficits" to be overcome in the pursuit of "normal" productivity. Instead, it prompts us to consider how these differences can uniquely shape, alter, or inspire creative content and process. For artists facing health challenges that alter their ability to create in familiar ways, there can be a sense of "disenfranchised grief" for the loss of that creative capacity. However, this perspective encourages us to explore "limitation as strength", allowing adaptations to become new creative paths , fostering a form of "post-traumatic growth" in the artistic journey. Embracing difficult emotions, and the physical experiences that often accompany them, becomes an act of radical acceptance and a source of profound, authentic art. This also applies to neurodivergent creativity, where unique aspects of the brain (e.g., ADHD, OCD, DID, mood episodes) specifically impact, alter, or inspire creative content or process.

The Nuance of Creative Wellness: Beyond the Dichotomy

It's crucial to understand that creative wellness isn't about avoiding challenging emotions altogether. It's about building a creative practice that honors your whole human experience, including the messy, difficult, and imperfect parts. This perspective moves beyond a simplistic binary of "art heals" or "art harms" to acknowledge the nuanced reality that art can do both, often simultaneously. The double-edged sword of creativity means it can be simultaneously healing and complicating.

Acknowledging the emotional bypass allows us to recognize when creating felt like it amplifies distress rather than relieved it. It pushes us to examine moments when creating leads to a "perfectionism prison" or results in an "isolation spiral" rather than restorative solitude. By recognizing these complications, we can develop strategies for creating in ways that fuel rather than deplete us. This requires a respect for our own boundaries, knowing when to push and when to rest.

Shifting from Bypass to Integration: Practical Strategies for Sustainable Creativity

To move beyond the emotional bypass, we need to cultivate practices that support emotional processing and integration. This is not about wallowing in difficult feelings, but about acknowledging them and allowing them to inform, rather than derail, your creative work. This proactive approach leads to sustainable practices.

Here are practical strategies for using difficult feelings as creative fuel:

Emotional Check-ins: Before you begin creating, pause and ask yourself, "How am I feeling right now, and how might this inform my work?" This simple act of awareness can open up new pathways for expression. This aligns with mindfulness practices, which cultivate present-moment awareness without judgment.

Prompt-Based Exploration: Instead of pushing emotions away, use them as direct prompts. If you're feeling anger, ask yourself: "What wants to be expressed through this anger?" If sadness is present, "How might this sadness inform the color palette?" If anxiety lingers, "What story is this anxiety trying to tell?". These questions transform internal states into external, creative inquiry.

Process Over Output: Focus on the act of creation as a means of processing, rather than striving for a perfect finished product. The value lies in the journey of creation, not just the destination. This allows for exploration and emotional release without the added pressure of external judgment. This shifts us from an "output obsession" to honoring the process , celebrating process victories, not just completed pieces.

Non-Judgmental Observation: Approach your feelings with curiosity rather than criticism. There are no "bad" emotions, only information your system is providing. This non-judgmental stance fosters psychological safety, allowing for deeper engagement with your inner landscape. It's about recognizing that the "mess is not a moral failing" , but rather data about your internal world. Disorganization, in this context, "becomes a form of data; it shows us when the overwhelm has pooled. It maps the stages of burnout, grief, avoidance, or even passive resistance. The mess becomes a marker of where something deeper needs tending".

Strategic Rest and Recovery Rituals: Emotional processing requires energy. Incorporate strategic rest and recovery rituals into your creative routine. Prioritizing diverse forms of rest and embracing principles of slower work and degrowth can create the space needed for emotional integration. As practices that support wellness (like adequate rest, emotional processing, and stress management) enhance creative flow, increase problem-solving ability, and improve the quality of our artistic work. This includes honoring your "energy awareness," recognizing your natural rhythms and working with them, not against them.

Reclaiming Your Creative Power

Choosing to integrate difficult feelings into your creative practice is a radical act in a world that demands endless productivity. It's a statement that your humanity matters more than your output , and that your long-term creative capacity is more valuable than short-term gains. When you allow your full emotional range to inform your art, you create work that is not only more authentic and sustainable , but also deeply meaningful. Your creativity doesn't need to hurt to matter , but it needs you, all of you, rested, aware, emotionally integrated, and creatively alive.

The world doesn't need more burnt out artists creating from obligation; it needs artists who are so well resourced and connected to their creativity that their work becomes a gift to both themselves and others. That's the power of putting creative wellness first. Not because it makes you more productive (though it often does), but because it makes you more you.

At my artist residency in Kenya, I taught an impromptu abstract painting class with a family from Nairobi the other day. I was talking about intuitive line making—and scribbling—as a way to start and ground a piece. One of little girls said: Sometimes when I’m mad I make big scribbles. This launched a conversation about making art as a way to process negative emotions.

Kids know.