Art and Mental Health History: Carlo Zinelli

Acknowledging the problems with the term "outsider art" while celebrating the work created by institutionalized Italian artist Carlo Zinelli

“Poetry and tragedy, presences and memories, flesh and mind, invocations and evocations, these (and many others) are the poles between which Carlo moves, offering us a dotted map of his thoughts.” - Marta Spagnolello

There have been times in history when individuals in asylums/ institutions/ inpatient care were able to, even encouraged to, create art. There have been times when they’ve been forbidden or restricted from doing so. And then there was Dubuffet’s Art Brut period in which those who created while in lifelong mental health confinement were elevated and celebrated … for better or worse. It’s a complicated time in history but from it comes an archive of inspiring work and human stories, including the work of Carlo Zinelli.

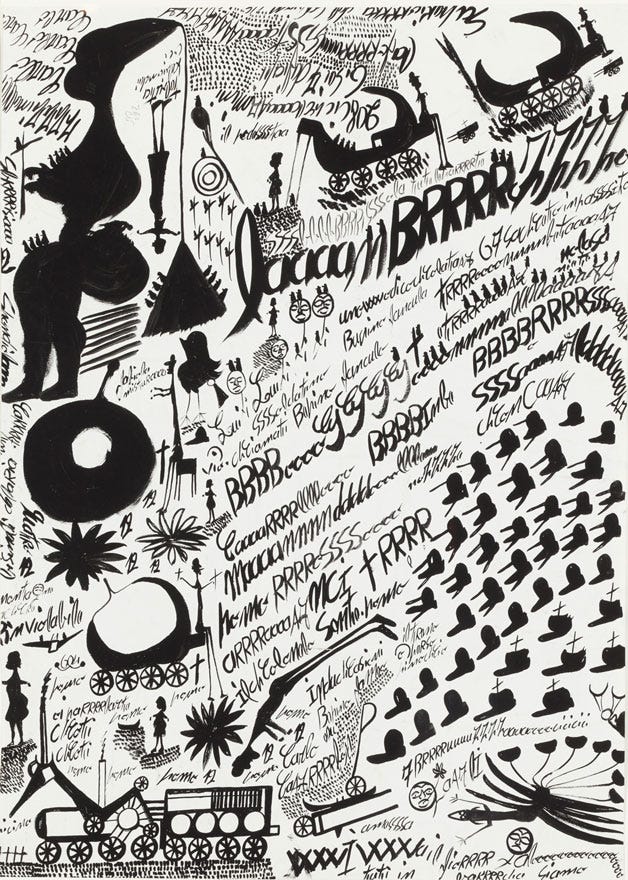

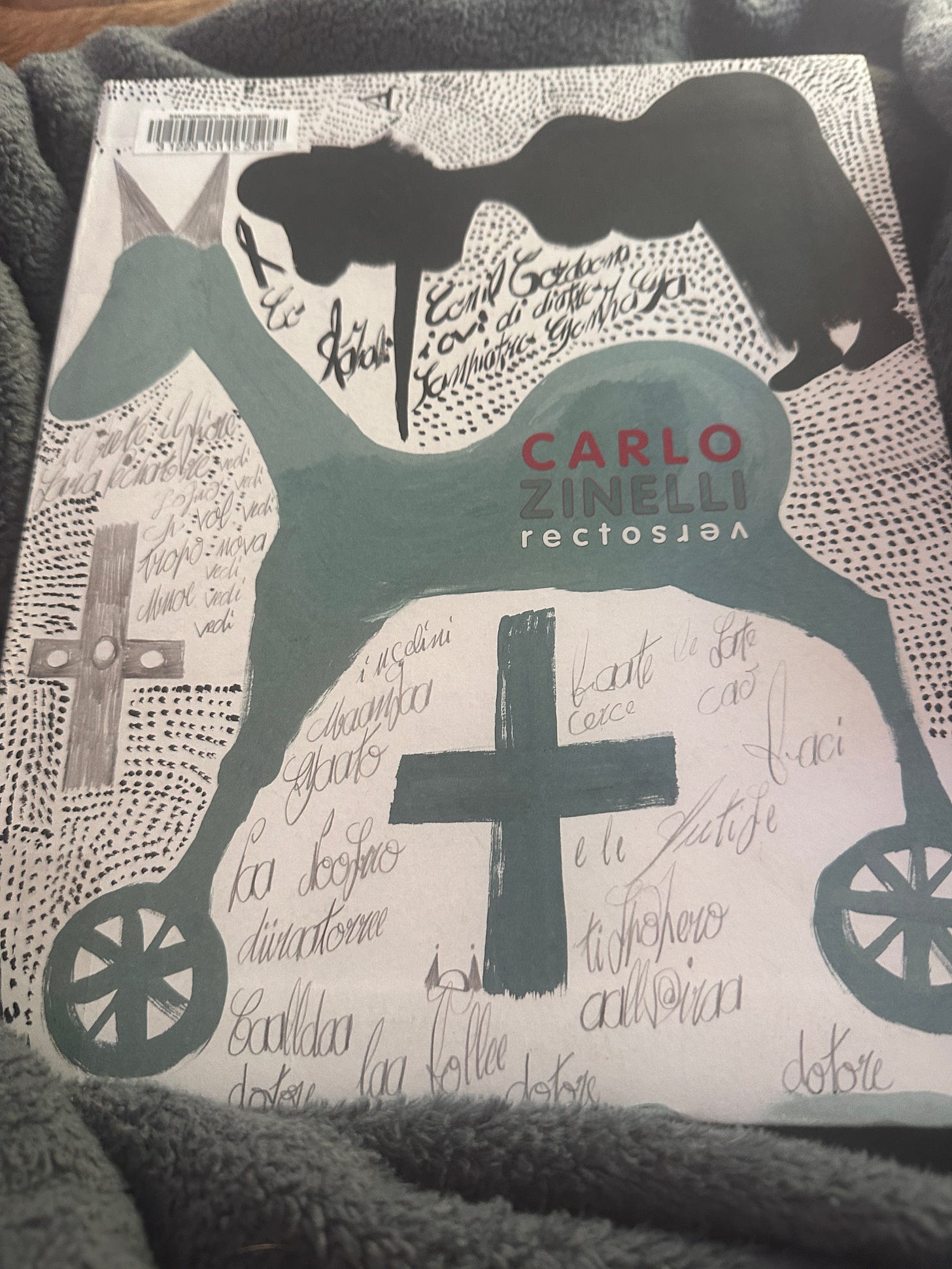

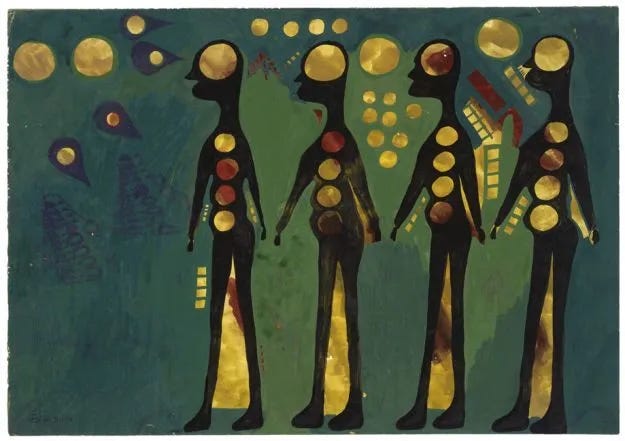

Zinelli is an artist “discovered” by Dubuffet and I could have, but didn’t, include him in The Artist’s Mind book in the chapter on “artists with schizophrenia and outsider art.” Today, I’ll share a version of the introduction to that chapter here to give you foundation for my beliefs about the complicated nature of defining “outsider art” and then I’ll share more about Carlo Zinelli. His work covers both sides of a page and stretches from end to end on each side, combining repetitive figures with looping text, sometimes incorporating mixed media collage, in a way that I find absolutely compelling.

Artists with Schizophrenia and Outsider Art

This section comes from my book The Artist’s Mind: The Creative Lives and Mental Health of Famous Artists.

When it comes to psychiatric issues, a strikingly large percentage of so-called outsider artists have a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is one of the most feared, stigmatized mental health issues to this day; when people think of someone “going crazy” they imagine the worst symptoms of schizophrenia, picturing delusions, violence, and “hearing voices.” While there can be extreme symptoms of schizophrenia, and it’s a challenging condition to treat, people can also live long, fulfilling, and creative lives with this diagnosis.

What is Outsider Art (And Is It Real or a Myth?)

“Probably no art so caters to the public's hatred of the establishment as outsider art. The work of the uneducated, the insane, the criminal and the underprivileged, outsider art preserves a myth of esthetic purity for a culture tired of its experts. The outsider artist has not suffered the deforming influence of art school, and his art requires no esoteric explanation from critics. Motivated merely by the joy of making art, the outsider is totally unaware, or so the story goes, of the history of art or of the marketplace.” - Wendy Steiner, The New York Times

“Outsider Art” is a problematic term and yet it is one that’s been historically widely accepted, so it’s important that we dissect it before we further explore artists who may (or may not) fall into this category. In brief, the term refers to art created outside of the traditional, formally and socially sanctioned art world. If many contemporary artists take a path that includes earning an MFA, interning or apprenticing with higher-ups in the art world, journeying through gallery representation with an eye on sales and exhibitions, etc., then outsider art is the opposite: self-taught artists working outside of those boundaries without connection to, or perhaps even any interest in, participating in the art market. That’s the basics. When we delve deeper, however, into who exactly gets the label of ‘outsider artist’, it becomes clear why the term is controversial, and how it directly links with perceptions of mental illness and the stigmatization of various groups

The term was essentially coined by French artist Jean Dubuffet in the 1940s; then called “art brut” which translates to “raw art,” this style of work was renamed “outsider art” in the 1970s by art critic Roger Cardinal. Dubuffet was captivated with art made by people in psychiatric institutions, and specifically inspired by the writings of German psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn which documented a wide array of asylum art. Dubuffet also included work by prisoners, mediums or clairvoyants, children, the elderly, and the uneducated. Subsequently, those who champion so-called outsider art have continued to focus on art created in institutional settings (by psychiatric patients as well as the imprisoned), along with art created by people with learning disabilities, mental health challenges, those who are homeless or underhoused, and other marginalized groups.

We can see immediately that there are a lot of problems with this label from the broad spectrum of artists included under its umbrella. While it’s certainly wonderful to acknowledge these artists in their own right, the history of the art world’s engagement with outsider art has been marked by a sort of patronizing privilege. In the same way that we would never say today that Christopher Columbus “discovered” America, it’s also problematic to say that someone from the art world (a critic, dealer, curator, etc.) has “discovered” an outsider artist. There is also an issue with insisting that outsider art is somehow “pure” or “untouched,” as if all the diverse artists who would supposedly fit into this category have no understanding of the world around them, and that their work is not just as contextual to specific cultural and social moments as the work of artists accepted by the establishment.

In an effort to correct the offensive terminology, art like this has more recently been called “self-taught” or “visionary” art. In the 1990s, Baltimore opened the American Visionary Art Museum, a place for “visionary and outsider art”, recognized by Congress as art "produced by self-taught individuals who are driven by their own internal impulses to create" and hailed as "a rare and valuable national treasure." The language here, and what originally drew Dubuffet and Cardinal to this work, suggests there is something special about art created purely by the desire to self-express, as opposed to work that caters to the whims of the art world and made in order to make a living. That point could perhaps be argued, but in the years since the movement has gained popularity, so-called outsider art often ends up just as mediated by the market as mainstream art due to the influence of dealers, buyers, and an interested public. The biannual Outsider Art Fair, held in New York and Paris, and accompanied each year by a dedicated Christie’s sale of outsider art, is one example of the diminishing difference in markets. (Owner of the fair Andrew Edlin estimates the outsider art market generates as much as between $40 million and $50 million each year.)

We could delve extensively into the topic of outsider art, as there is extensive critical research dissecting the term and its history, however, most of that scholarship is outside of the scope of this book. What we can’t neglect, though, is the direct relationship between mental health stigmatization and the appellation of outsider art. As we’ve seen in the previous chapters, people can live, work, and create despite devastating mental illness, so simply having a diagnosis (or being undiagnosed but with all the obvious symptoms of a mental illness) does not automatically qualify one as an outsider artist, however fraught the term.

Historically, a white male could exhibit signs of mental illness, even spending time in an asylum, and yet be an accepted, even canonical artist (Vincent van Gogh being the obvious example.) Women and people of color less so, but some achieved this acceptance, though often these artists were somehow associated with notable white men, and for many recognition came later thanks to revisionist art historical studies with a focus on gender and race. Some examples we have covered include Frida Kahlo (a woman of color who certainly gained recognition in her own right, but was also undeniably linked with Diego Rivera) and Camille Claudel (who was better known as Rodin’s mistress than an artist in her own right until relatively recent feminist reinterpretations of her work.) As Wendy Steiner puts it, “There is not a single criterion of "outsiderness" that cannot be found in "inside" artists. Van Gogh was mad. Joseph Cornell was self-taught. Caravaggio was a criminal. El Greco was a visionary. Socially deviant high artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat are a dime a dozen. Chagall's paintings are as full of fanciful folk elements as any outsider artist's work, and everyone from Duchamp to Rauschenberg has made art out of scraps and refuse.”

Often, the artists who managed to “make it” are those who have a combination of privilege and access, both socially and financially, that make it easier to live with their symptoms and achieve acceptance as an “insider.” Richard Dadd was white, male, and affluent so despite being ending up in a psychiatric hospital for patricide, he was never considered an “outsider artist.” It’s not easy to create a career out of art when so much of success isn’t related to art making at all, but instead relies on networking, marketing, and so forth. It can be too much for someone who is simply trying to get through everyday life with the symptoms of a mental health condition. If someone’s symptoms, combined with trauma and other factors, means that they’re often homeless or underhoused, or spend a lot of time in and out of institutions (psychiatric and penal), then they cannot participate in the conventions that traditionally mark mainstream success. These people are stigmatized for a variety of reasons, so when an art world insider “discovers” their work, they are also glorifying the very things that stigmatize the person in society, not to mention taking credit for “bringing the work to light.”

Moreover, mental health is incredibly nuanced, with so much grey area, the broad term does a disservice to the individual. How do we categorize Yayoi Kusama, for example, in the context of outsider art? In many ways she was an outsider in the New York art world, being both a woman and Japanese, but she did manage to navigate that world to great success. Yet, after her major breakdown, she checked herself into an asylum where she has lived and created for decades. Had she not managed to make a name for herself first, had someone else happened to notice her work at the asylum and promote it, then would she be considered an “outsider artist”? What about Diane Arbus, who was born into privilege but felt like an outsider and arguably tried to make herself one by photographing people in the fringes of society; yet she always kept one foot in the world of her birth, continuing to photograph friends, celebrities, and the wealthy at the same time. Can you cross from “insider” to “outsider” by choice? Did her experience of deep depression make her feel like an outsider and if she felt like one, is there any validity to that?

It’s a tricky thing to define all of this. One suggestion is to banish the binary and instead place artists on a spectrum from “outsider” to “mainstream,” a solution which at least recognizes that it’s a blurry distinction influenced by a person’s education, psychology, status in society, and many other factors. How to actually define the points along that spectrum is a murky endeavor, but it’s better than the black-and-white notion of either being in or out. It’s something worth keeping in mind as we explore the artists in this chapter, because their relative access to services, treatment, and support may have played a key role not only in the treatment of their mental health challenges but in how their artistic lives unfolded as well.

Carlo Zinelli

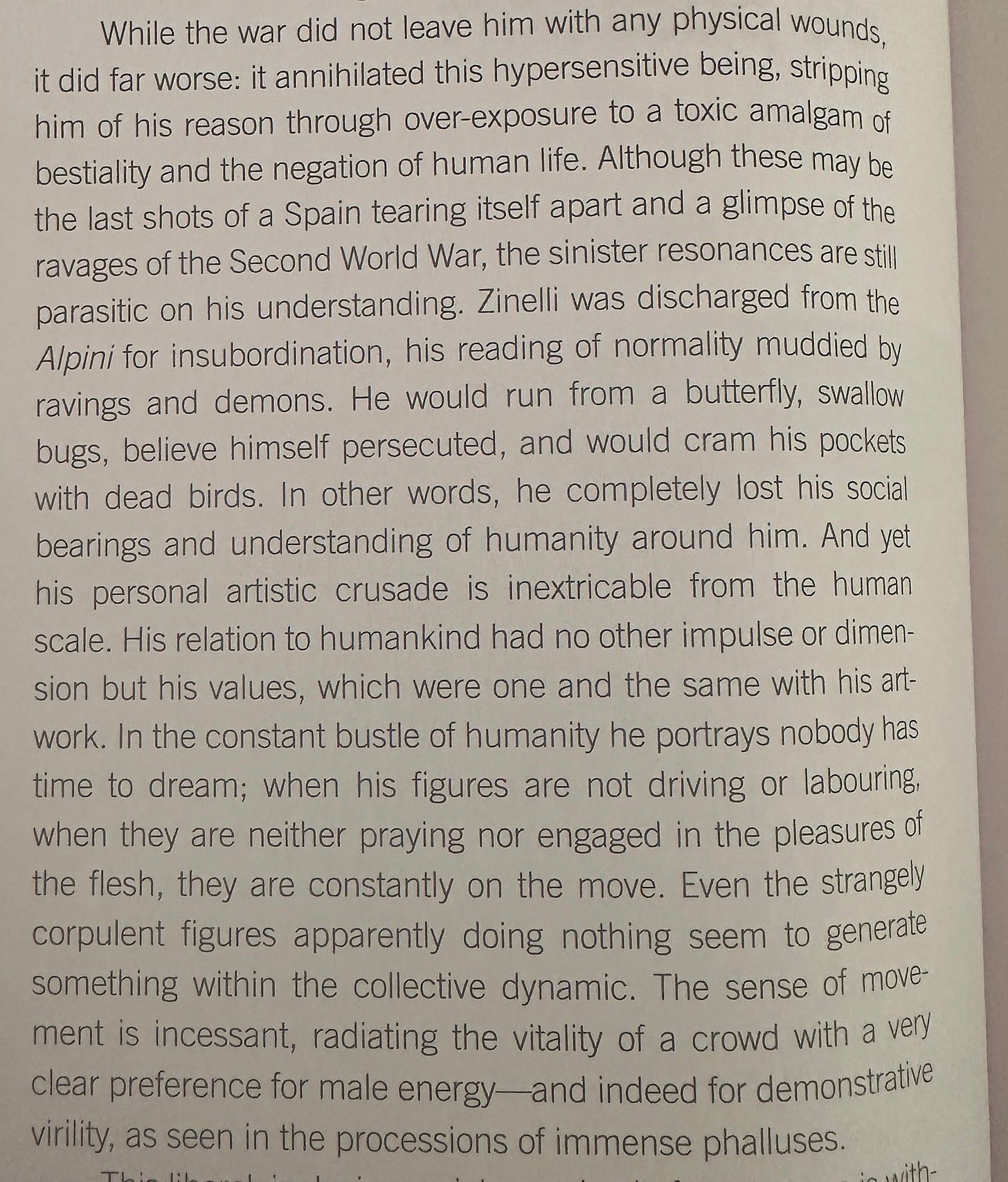

Carlo Zinelli was born in San Giovanni Pupatoto, Italy, in 1916, only two years before his mother died, so he grew up in a home steeped in grief. It was also mired in poverty and he left school at age nine to work on a farm. At 18, he moved to the city of Verona and worked in a slaughterhouse, an intense job that contrasts interestingly with his study of music and beginning to paint at this time. At 20, he was called to war, the various horrors of which seem to have led to a mental break. For the next five years, he was in and out of military service, in and out of war settings, in and our of the military hospital, in and out of “episodes of aggression and terror.” Throughout, he sent postcards to his family, always incorporating drawings into them.

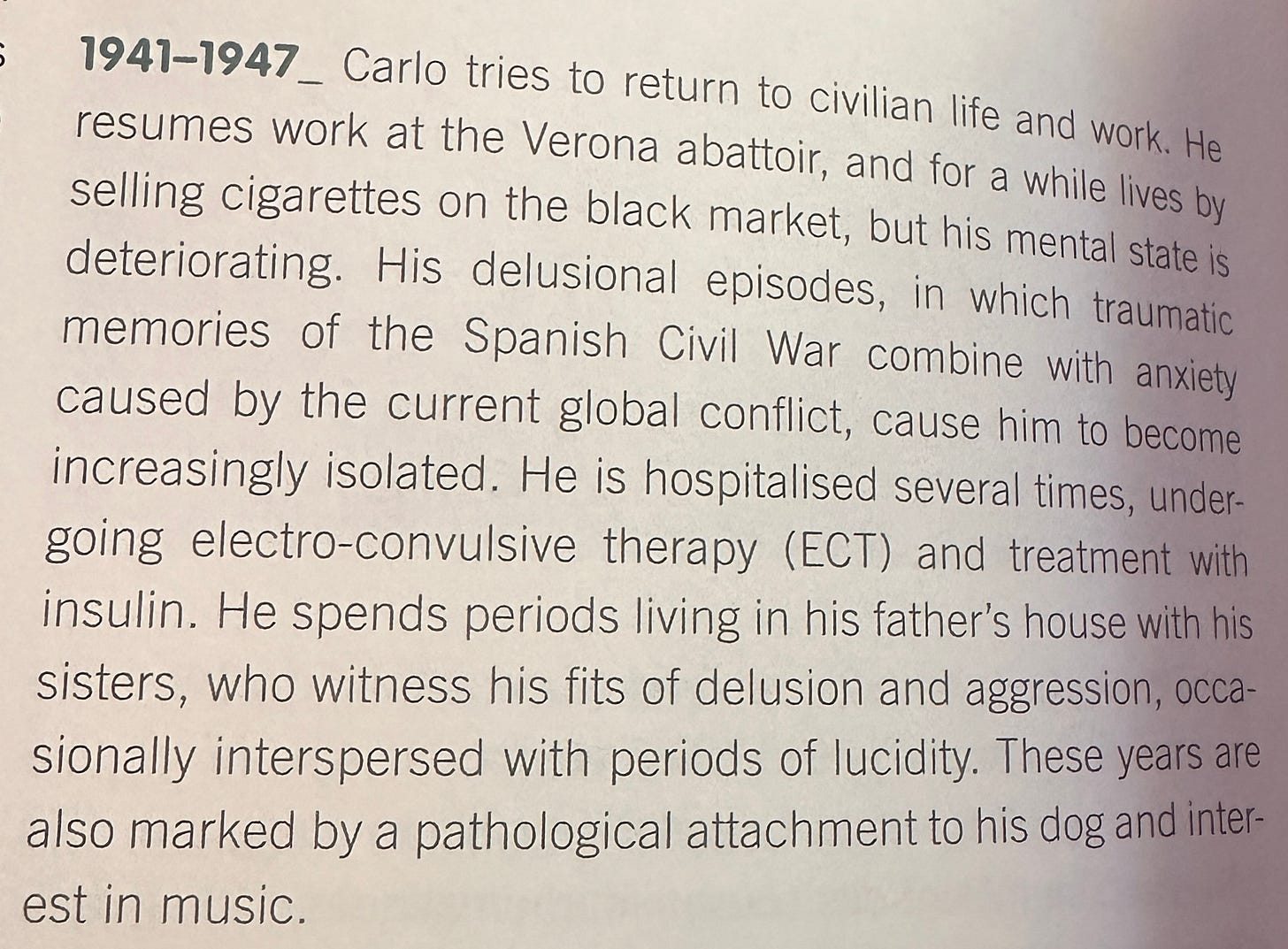

In 1941, his brother, diagnosed with paranoid psychosis, himself returned from war, moved to a psychiatric hospital and died there. That same year, Carlo left the military and tries to return to life in Verona but his mental health made it challenging. Here’s an entry in the timeline at the back of the aforementioned catalogue:

I find myself so intrigued by that last sentence. Here’s another description of his experience at the time, and its relationship to his eventual artwork, from Florence Millioud Henriques:

In 1947, he went into a psychiatric hospital, was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and declined rapidly over several years there. He became mostly non-verbal, aside from ranting repetitive phrases seemingly to himself, when not basically made comatose by the tranquilizers given to the patients there. This more or less continued for a decade.

Between 1955 and 1959, things shifted for Carlo and within the institution. Psychiatric care was changing. An art studio was established on the grounds of the hospital. Carlo attended some art lessons but the academic rigidity of them didn’t work for him (or most of the patients for that matter) and he stopped attending. However, he was often seen creating art from the random materials available around him - carving images onto walls with stone, drawing in the dirt with sticks, using his saliva and leaves to create images.

In 1959, the institution opened a new art studio that is much more free-flowing. At the same time, a very young psychiatrist-in-training visited the institution and became enamored of Carlo and his art. He will advocate for him, befriend him, and eventually petition to have him taken off of the paralyzing tranquilizers that stifle him. He’ll also make his own name writing his thesis and professional papers about Carlo; again, this “outsider art” particularly in this era is complicated. Regardless, what comes out of it all is that for the next decade Carlo Zinelli was always in the art studio, creating, his mental health and general wellbeing seeming to improve. In this decade, he painted prolifically.

In 1969, however, the institution he had been living in was closed, and he moved to another hospital where there was no art studio. His mental health declined, his agitation increased. At some point, he left the hospital to live with his brothers for a couple of years, his physical health was not well, and he didn’t paint much at all. He moved to a sanitorium for people with tuberculosis where he died in January 1974.

Notable Moments in the Rectoverso Exhibition Catalogue

Here are some things I read throughout the pages of the aforementioned book that I wanted to highlight.

How Art May Have Helped Carlo Zinelli

“Simply put, the artist’s powerful, poetic expression coalesced in an environment of violence and abandonment. We can assume that for Carlo, his work was a means to escape suffering and sickness … and that the act of creating was a means of survival.” - Sarah Lombardi

I’m not sure that we should assume anything. Nevertheless, I find myself drawn to believing in the perhaps-romanticized idea that self-expression through art was a salve to a difficult experience of life (whether that difficulty was internal to his brain, external to the circumstances of the institution or both).

“Carlo himself did not consider his art as in any sense forming an “oeuvre,” however, but as a kind of personal chronicle in which he set down, through images and words, his memories of childhood and everything that he loved in life - music, nature and animals, particularly birds.” - Sarah Lombardi

Florence Milliouid Henriques posits:

“As though, brush in hand, the former soldier, the “madman” banished from society, was merely liberating memories that neither ECT nor sedatives had managed to erase.”

But then adds:

“We must accept not knowing whether he was constantly reliving his life or whether he was drawing another life on the basis of his own landmarks … To say that as an artist he was driven solely by the need for catharsis would be an oversimplification.”

Michael Noble says of Carlo, “I think, though, that what mattered most to him was the calm everyday rhythm of the studio.”

Dubuffet’s View of Carlo Zinelli and Outsider Art

The young psychiatrist Andreoli visited the institution in 1959 where he saw over 1000 patients across the grounds but was most intrigued by the twelve patients in the painting workshop.

“Trabucchi invited Andreoli to return and attend the studio sessions, which the hospital’s other psychiatrists regarded as “pure folly.” - Anic Zanzi

He did, of course, focusing particularly on Zinelli’s work. Five years later, he would take over as the art studio’s manager. During this time, he showed Zinelli’s work to a collector who in turn tried to interest Dubuffet in it. Dubuffet was enamored of the idea of schizophrenia artists compelled to create art with no training or support and he initially showed skeptical interest in Zinelli’s work, writing in a letter:

Dubuffet goes on to express concern “that this Carlo is given far too much encouragement to draw.” Which speaks to the complicated essence of this whole outsider art period and Dubuffet’s role in it. Dubuffet was aligned with the Surrealists and believed deeply in spontaneous, subconsciously-driven art, as opposed to structured art, art created in a studio, art that is built upon any lessons. Dubuffet, despite collecting Zinelli’s art and arguably profitting off of it, continues to remain skeptical that Carlo might be producing artwork because he’s encouraged to do so and so the work is different than if he’d done it on his own in secret.

“The key to “art brut” is that it does not know it is art, it’s art that does not know its name, produced in the fever of creativity and with no other purpose. Instead, in the case of Carlo Z. it feels as though there is a purpose. It probably doesn’t come from him, but from those who support and direct him, who organise exhibitions of his paintings, and who are even inclined - as I understand it - to somewhat vulgarly promote them and introduced them into commercial circuits.”

Outsider Artists In Institutions

Regardless of the skepticism, Carlo’s work helped make up the core of Dubuffet’s collection, alongside Aloise Corbaz and Adolf Wolfli.

“After chaotic lives and, for different reasons, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, all three were hospitalized in their early theries and spent the rest of their days in a pscyhiatric institution. In these places that might initially seem unfavourable to creativity, they nevertheless made hundreds of drawings and paintings. …

“Upon being locked away in a psychiatric institution, after several difficult years of adjustment, they started to give vent to their creativity, and from that point on interment seems to have offered them the opportunity of a form of inner exile, autonomy, and deliverance.” - Anic Zanzi

I don’t believe in binary stories particularly where art and mental health are concerned. I don’t believe that each man’s life was entirely terrible before institutionalization or that creating art while inpatient was always beneficial. But I do believe that there’s likely truth to those things and would love to know all of the other truths on this spectrum of experience.

Valerie Rousseau writes of the photojournalism by John Phillips depicting the institution:

“Phillips’s images are effective in conveying the atmosphere and liberating impact of the studio, with its artists totally absorbed by their work. These images contrast with those taken in other parts of the asylum, depicting the harsh everyday realities of torment, confinement, and the concentration of psychological distress.” …

“Phillips arrived at a turning point in Zinelli’s life, which saw him embark on his work as an artist. At this crucial moment he gave a new function to a system of sounds, colours,m words, and images, where imprisonment and its disorienting realities were diverted into a period of reconstruction through formal experimentation, chromatic exploration and linguistive fragments.”

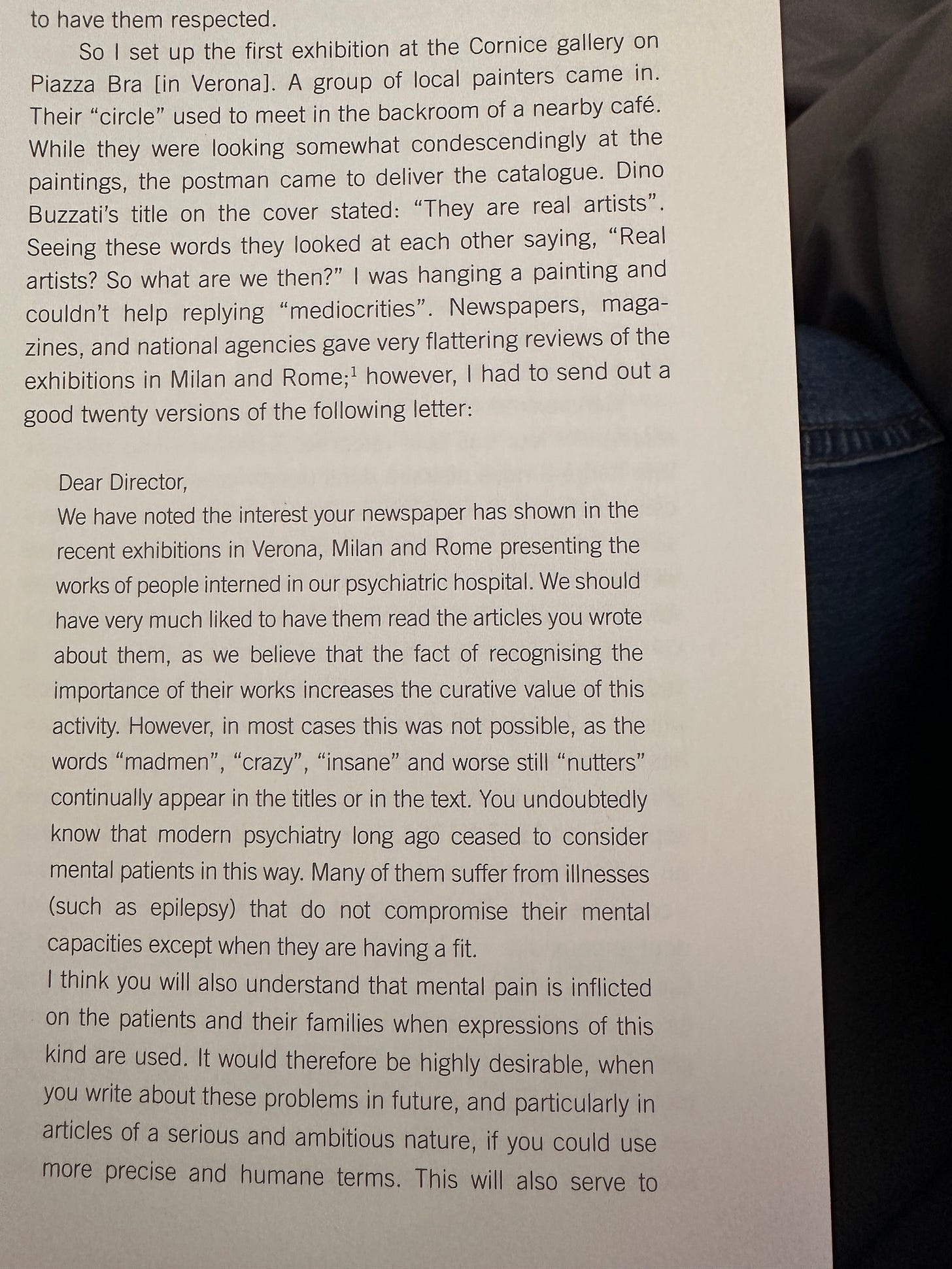

Stigma and Creativity

This excerpt from the piece written by Michael Noble was so powerful for me to read, as it speaks to the stigma of those with mental health conditions but also the many people over time who have worked to change that stigma.

Impact of Carlo’s Art on the Viewer: Slowing Us Down

I am gripped by this description from Marta Spagnolello, who has a terrific essay in the catalogue about the use of words and poetry and graphic text in his work:

“The total opposite of a page of hypertext, where our eyes move in a thousand directions, generation confusion and dispersion, Carlo’s work obliges us to concentrate.

In this way the dissociation we mentioned in relation to the artist’s life and works seems to be reproduced in the observer (or reader), who must disconnect from the rapid rhythms of society to focus on a patient search that takes its time.”

If you read this far, perhaps you liked the work. The work does take work. It only continues with support, so please consider subscribing. My annual rate starts at $10 per year.

You Might Also Like to Read:

Info/ Quote Sources:

Rainaldi, L. (2015). Outsider art: Forty years out (Electronic Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 2008+). University of British Columbia. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0221495

Schuster, C. (2020). In NYC, a fair dedicated to outsider art cultivates an interest in the eccentric. Observer. https://observer.com/2020/01/outsider-art-fair-market-growth-in-new-york/

Steiner, W. (1996, March 10). In love with the myth of the 'outsider'. The New York Times, p. 45. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/10/arts/art-view-in-love-with-the-myth-of-the-outsider.html

The Art Brut Collection: Carlo Zinelli - Recto Verso (5Continents, 192-page paperback, ISBN 9788874398522).

The Collector. (n.d.). Diane Arbus: The photographer of “freaks.” Retrieved from https://www.thecollector.com/diane-arbus-photographer/

Wow, this article/excerpt is fantastic, thank you so much for making this open access!

I had to move this topic to a footnote in my last article because there just wasn't the space to do it justice. So happy to have such a good piece to link to.