Akmaral: Author Interview with Novelist Judith Lindbergh

"Imagine a culture where women didn’t have to prove their value or their strength, where they didn’t have to fight for their right to personhood, where they were fierce and free to choose ..."

When I received the email announcing the book launch for Judith Lindbergh’s new novel Akmaral, I immediately paused to learn more. The story itself intrigued me and I also found myself wondering about some of the mental health aspects of the book’s writing process. So, I reached out to the author to see if she would be willing to do an interview with me about the book, and she generously responded with these terrific insights and elaborations.

What was the initial spark that made you interested in telling this story?

Akmaral began when I happened upon a documentary on PBS about the amazing Siberian Ice Maiden discovered on a high, lonely mountain pasture in the Altai Mountains just where southern Siberia meets Mongolia, northwestern China, and Kazakhstan. It’s the middle of nowhere, but just the kind of landscape that catches my breath and makes me fall in love.

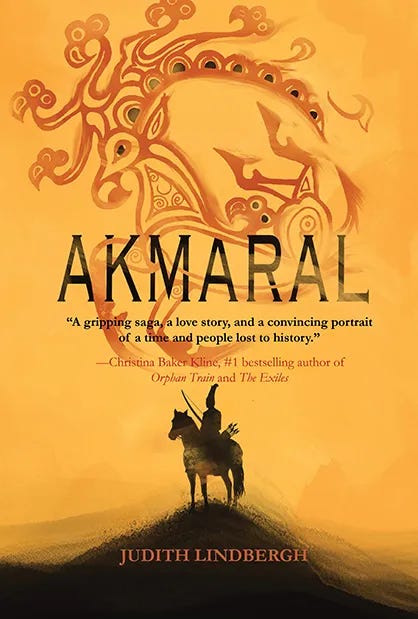

The burial itself was extraordinary: a woman’s body perfectly preserved in ice for over 2400 years. She was laid to rest in a massive larch-wood coffin wearing a tall headdress decorated with rich gold ornaments. Six horses were sacrificed in her honor, their ornate felt applique saddlecloths still intact. The Ice Maiden’s body was covered with tattoos of wild animals, including a “flying deer” which was an important spiritual symbol for the horseback riding herders of the steppes—and now graces the cover of my novel!

In my research, I discovered the connection between these mounted warriors and the Amazons of ancient Greek myth. The historian Herodotus tells that the Amazons joined with a group of Scythian warriors and eventually went off on their own to become the Sauromatae, which became my characters’ cultural group. I also read about the “Issyk Gold Man” found in the 1960s in Kazakhstan. Along with thousands of gold arrow-shaped ornaments, the body was buried with weaponry, so archaeologists assumed that it was a man. But more recent scholarship suggests that the warrior may have been female. This set my imagination on fire as I discovered real evidence of women warriors all across the steppes. Slowly, as I put together more remarkable discoveries and details, I began to sense Akmaral, a woman warrior and eventually a military and spiritual leader, forming in my mind.

We live in a time when it can feel so easy to research just about anything ... and yet, it sounds like there wasn't a lot of historical information about the era you were writing about. What was your research process like?

There is general information about the Scythians available on the internet. And you can search up practically every classical Greek reference ever made to the Amazons, or read all of Herodotus online for free. But for a book like Akmaral, I had to dig deeper, especially into the scholarly research of experts in the field. I’ve read countless archaeological reports, anthropological studies on related contemporary cultures, exhibition catalogues, and much more. And I’ve asked for guidance from experts, including one of the archaeologists who was featured in the original documentary that started me on this journey, the late Jeannine Davis-Kimball, Ph.D. Her book, Warrior Women, shifted my focus from the Siberian Ice Maiden, who appears to have been a priestess, to the Issyk Gold Man, who was clearly a warrior. Akmaral, in the end, is a fusion of the two.

Because my children were young when I began this novel, I couldn’t travel to Central Asia as I travelled to Greenland for my first novel, The Thrall’s Tale. Instead I rode the Mongolian steppes and stood atop the Altai peaks through the vivid reality of Google Earth. I spent countless hours perusing the extensive virtual Scythian and Altai collections at The Hermitage, a museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. And I borrowed traditions from modern day nomads who still live in Mongolia and Kazakhstan. I dug backward and forward in history, finding clues to my characters’ spiritual beliefs in Bronze Age artifacts and petroglyphs that dot the Central Asian steppes as well as folktales from the region and anthropological studies of nomadic herders who still live in Siberia.

How did writing the more intense war scenes impact your mental health/ sense of wellness/ nervous system?

Anyone who knows me will tell you that I am the least likely person to kill anything, even an insect that accidentally flies into my kitchen. I meditate and do yoga. I take long walks in the woods. When raising my sons, I tried hard to encourage gentleness and gender-neutral, nonviolent toys. So, needless to say, writing the battle scenes was truly a challenge. But the violence in Akmaral isn’t bloodthirsty or gratuitous. In fact, when I talk about the book, I say it’s about a woman making peace with making war. The battle scenes are almost always defensive, and when a character seems to take pleasure in violence, Akmaral’s people condemn and punish their behavior.

For me, facing battle, I’d gird myself by playing some very somber music—it’s traditional “Tuvan throat singing”—music from the region where the book takes place, heavy with deep droning and ominous overtones. The weight of the music prepared me, as it prepared Akmaral, to face the horrors that were also necessities. If they didn’t face their enemies, who were fully prepared to kill them, they and everyone they loved would be killed. From that knowledge, and that deep love and necessity to protect, I found the strength to write the words with all the seriousness and respect that the scenes required.

How do issues of mental health/ wellness/ psychological challenges show up in the characters of this book?

One of the main characters struggles with terrible anger and insecurity. His challenges are rooted in a wrong-headed belief that his family, and therefore he, is cursed by their people’s gods. Akmaral’s clan believes in the power of nature to control and direct their fate. For example, they are terrified of lightning for obvious reasons. Imagine a thunderstorm on a huge, open grassland where there’s virtually no shelter, not even trees. So when this character’s family is killed by a lightning strike on their yurt, he takes it as an omen of the gods’ displeasure. As a young man, he masks his fear with bravado and aggression, often directed at Akmaral. But over the course of the novel, which takes place from their youth into adulthood, he grows and redirects that terror into fierce loyalty aimed at protecting their tribe at all costs. At times, his actions are honorable and correct, but at other times, his extreme responses create a ripple effect that shifts the course of all the characters’ lives.

How would you say these women warriors relate to other women warriors from history, literature or contemporary film/books?

Of course, when we think “Amazons” most people will think of Wonder Woman, who was supposed to be an Amazon before she left her hidden island and joined the human race. And there have been other women warriors throughout history. Joan of Arc and Boudicca come to mind. There are legends that Mulan was based on a real woman. And there’s truth behind the movie The Woman King. But Akmaral is not a superhero. And she’s not based on any specific woman in history. She is a combination of many burials that provide undeniable, physical evidence that these warrior women were real.

From the archaeological record across the Central Asian steppes, women fought in battle frequently, clearly died of their battle wounds, and were buried with their weapons and battle gear. It’s also clear that they were leaders of their tribes from their central placement in burial mounds and from their rich grave goods. To me, that means there was a moment in history when women were implicit equals. These warriors were not outliers who went against societal norms or who rose up due to a specific, imminent threat. There are simply too many female warrior burials that prove otherwise.

Imagine a culture where women didn’t have to prove their value or their strength, where they didn’t have to fight for their right to personhood, where they were fierce and free to choose their own paths. To me, this is an empowering piece of history that deserves more attention.

What was one of your biggest creative challenges in writing this book and how did you work through it?

Other than dealing with all of the violence? Honestly, that was the hardest thing for me—to embody my characters and let them kill. I needed to find a strong rationale, and I had to be ready to deal honestly with the complex emotional and physical consequences of their actions.

In the last part of the book, Akmaral makes a choice that changes the way her people deal with violence. Her choice changes everything and sets her people on a path to a very different future. In a way, that choice was also my own—a moment in which I could reassess the behaviors that are called “human nature” and take a chance on a different way of being. If only I could make that happen in real life and not just in my fiction!

Do you have any excerpts that ended up on the cutting room floor but that you'd love to see shared now?

There are some beautiful scenes of ancient rituals and healing practices that I worked very hard on, researching deeply into shamanism as it has been practiced by traditional peoples in the region for millennia. The rituals are long, complicated, and sometimes difficult to comprehend. But I loved writing them and trying to understand them. In the end, they really weighed down the pacing of the book, so they were cut. But sometimes I go back and think about what I could do with them.

I also cut or trimmed a number of scenes showing traditional felt-making, bow construction, how to raise a yurt and milk or butcher horses for meat. Sometimes we historical novelists get so caught up in our research that we think everyone is going to want to know—in extreme, replicable detail—how things were done and life was lived back in the day. But most people don’t have that obsession or patience. Readers want a good story and characters they can root for. But if you’re like me and really want to know, reach out to me. I know exactly which books to recommend to you. See Judith’s selected resources and references here.

What do you most hope a reader gets from this book?

No matter the cultural differences, I want readers to know that ancient people were fully human. They had the same desires and struggles as modern people do. We all want food in our bellies and a peaceful night’s sleep. We all want acceptance, friendship, family, and love. We all want to pass on something, however small, to those who come after us. And we all love our children. These deeply human truths guide me in all my fiction, even as I weave a tale of the distant past.

I also want readers to know that there really was a time in the ancient past when women were equal. And they didn’t have to be outliers or go against social norms to be powerful, independent, and valued for those qualities. If ancient people could honor women’s agency, maybe modern cultures can learn to do that, too. Being a strong woman doesn’t mean that we have to give up our femininity or our desire to have children. We can be leaders and also mothers. We can be lovers and also friends—with men as well as women. Western traditions have put men and women into very distinct roles. But in a time and place where everyone must pitch in to survive, those narrow roles lose their value. If we think about our modern world as a little bit smaller, and all of us as a little more connected than we currently feel, maybe those deeply divisive boundaries between us can disappear, too.

About Judith Lindbergh

Judith Lindbergh’s new novel, Akmaral, about a nomad woman warrior on the ancient Central Asian steppes, is available from Regal House Publishing. Her debut novel, The Thrall’s Tale, about three women in the first Viking Age settlement in Greenland, was an IndieBound Pick, a Borders Original Voices Selection, and praised by Pulitzer Prize winners Geraldine Brooks and Robert Olen Butler. Her work has appeared in numerous publications including in Newsweek, Zibby Magazine, Next Avenue, Writer’s Digest, Edible Jersey, Literary Mama, Archaeology Magazine, Other Voices, and UP HERE: The North at the Center of the World published by University of Washington Press. She has spoken at and published with the Smithsonian Institution and provided expert commentary on two documentary series for The History Channel. Judith received a 2024 Fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts. She is the Founder/Director of The Writers Circle, a New Jersey-based creative writing center where she teaches aspiring and accomplished writers from ages 8-80.